by Debra Brown

Mental and emotional illnesses have had many "causes" over the millenia, from demon-possession to "sainthood" or "witchcraft".

Treatment, of course, was determined by the "cause". Skulls from the "Stone Age" have been found drilled with holes, probably to release demons which were believed to be causing the person's illness.

Plato (428 - 348 B.C.) believed that there were three possible causes of mental disturbance--disease of the body, or imbalance of base emotions or intervention by the gods. He wrote about conditions that are recognized today--melancholia or depression, in which a person loses interest in life, and manic states, in which a person becomes euphoric or agitated. He argued that these be treated, not by chanting priests with snakes, but by convincing the person to act rationally, threatening him with confinement or rewarding him for good behavior. There was hope even then!

Hippocrates (c. 460 - 377 B.C.) proposed treating melancholia by inducing vomiting with herbs to rid the body of humors, specifically black bile. Then the body was to be built up with good food and exercise. He taught that pleasures, sorrows, sleeplessness, anxieties and absent-mindedness came from the brain when it is not healthy, but becomes "abnormally hot, cold, moist, or dry ... Madness comes from its moistness".

The Greek physician Claudius Galen (A.D. 129 - 216) accepted the theory of humors, but he dissected cadavers to study the body, and he believed that a network of nerves carried messsages and sensations to and from every part of the body to the center of the nervous system, the brain.

The common people, however, rarely heard any of these reasonable explanations.

While sophisticated progress was being made in many places on the earth during the Dark Ages - Medieval period, Europeans equated madness with demonic possession or witchcraft. Fear of madmen showed up as taunting and abuse. Ship's captains were paid to remove mad persons to distant towns. They were driven out of the city walls at night along with lepers and beggars. Poor Tom in Shakespeare's King Lear was forced to fend for himself in the woods and fields:

"Poor Tom; that eats the swimming frog, the toad,

The tadpole, the wall-newt and the water;

That in the fury of his heart, when the foul fiend rages,

Eats cow-dung for salllets; swallows the old rat and the ditch-dog;

Drinks the green mantle of the standing pool;

Who is whipped from tithing to tithing,

And stock-punished, and imprisoned;

Who hath had three suits to his back, six shirts to his body,

Horse to ride, and weapon to wear;

But mice and rats, and such small fare,

Have been Tom's food for seven long year."

Some fared better. If a disturbed person came from a loving aristocratic family, they might be sheltered in a castle's turret. Treatment might be sought from a priest; a relic, an item reputed to have been touched by Jesus or a saint, might be applied, or an exorcism performed. They might even seek help from a physician who had studied the writings of Hippocrates or Galen. Poor folk sought cures from women who blended superstition and a knowledge of herbs. One such was recorded in The Leech Book of Blad, compiled in England in the eleventh century:

"When a devil possess a man or controls him from within with disease, [give] a spew drink [to cause vomiting] of lupine, bishopwort, and henbane. Pound these together. Add ale for a liquid. Let it stand for a night. Add cathartic grains and holy water, to be drunk out of a church bell."

If the illness manifested as obsessive praying, fasting to the point of starvation or claiming to see visions, the person might be thought to be in special communication with the Holy Spirit. Others were not so fortunate.

Freedom of speech and religion had no place in medieval Europe. The Church maintained its power by instilling fear of punishment in this world and terror of damnation in the next. Any opposition meant heresy, and heresy was punished by death. Thousands of Jews were executed for religious heresy.

"Witches", who did the devil's work on earth, were heretics of the highest degree. In 1484 Pope Innocent VIII isued a Bull calling upon the church to seek out and eradicate witches throughout Christendom. How were they to be identified? Two German monks, Heinrich Kramer and James Sprenger, published a book called Malleus Maleficarum or The Hammer of Witches explaining how they could be recognized and prescribing methods for making them confess. Anyone who tried to oppose the witch hunt would himself be suspect!

"All wickedness" they wrote, "is but little to the wickedness of a woman. Wherefore St. John Chrysostom says: 'It is not good to marry, What else is woman but a foe to friendship, an inescapable punishment, a necessary evil, a natural temptation, a delectable detriment, an evil of nature, painted with fair colors!'"

Any woman who talked wildly, wandered aimlessly, and insisted that she heard strange voices or saw visions was likely to be a witch. Inquisitors would be sent to extract a confession. She would generally confess under torture. For two hundred years, clerics referred to the pages of Malleus Maleficarum, arresting tens of thousands of supposed witches, many of whom were likely mentally or emotionally ill women, and sent them to their deaths.

By the early seventeenth century, the hunt for heretics had lost its driving force. The mad were seen, more and more, to suffer from a form of illness. They needed protection--and society needed protection from them.

I love the title of the fourth chapter of my resource, Out of Mind, Out of Sight. Allow me to quote from the book, which is titled Snake Pits, Talking Cures, & Magic Bullets: A History of Mental Illness by Deborah Kent.

"When St. Mary of Bethlehem Priory, in London, opened its doors to the sick and destitute in 1329, its nuns acted within the longstanding tradition of Christian charity. At first they took in only a few unfortunates at a time--perhaps a dying leper, or a frail old woman in need of shelter. In 1375 the priory was seized by the Crown, and in 1403 a royal edict turned it into a 'madhouse,' or shelter for the insane. Records show that the madhouse held six insane men during its first year of operation. The city of London took over the hospital in 1547, and it served as a city hospital for the mentally ill until 1948. By Shakespeare's time the name Bethlehem was shortened to 'Bedlam,' a word that endures in the English language to this day, connoting unbridled noise and disorder. The word carries an echo of the cacophony that must have reigned in that London institution some five hundred years ago."

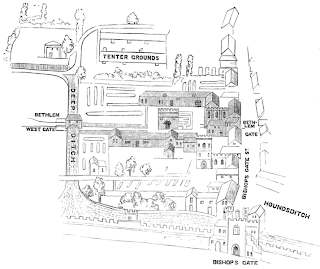

|

| Plan of the First Bethlem Hospital from Daniel Hack Tukes' Chapters in the History of the Insane in the British Isles (London, 1882), p. 60. |

Perhaps a reason for that cacophony, besides the mental illness itself, is brought out by Urbane Metcalf in The Interior of Bethlehem Hospital, 1817:

"It is to be observed that the basement is appropriated for those patients who are not cleanly in their person, and who on that account have no beds, but lie on straw with blankets and a rug; but I am sorry to say it is too often made a place of punishment to gratify the unbounded cruelties of the keepers."

By the middle of the seventeenth century, hospitals sprang up all over Europe. These early hospitals were not so much designed to heal the sick as they were to protect society from them. The sick and poor might be brought by officials, and some persons, desperate with poverty, pleaded for admission. The hospital provided food and lodging, but it exacted a heavy price in suffering and humiliation.

"Inmates" were often kept in damp, or even wet, conditions, cold in the winter, and many were bit by rats. Some were kept in cages and fed like livestock. To the hospital directors, the workers and the general public, the inmates were not fully human. The rational mind was the essence of humanity.

Kent writes that "In 1815, testimony before the British House of Commons revealed that curious visitors were admitted to view the lunatics at Bedlam for a penny each Sunday. In one year Bedlam collected four hundred pounds in pennies from some 96,000 visitors."

While public hospitals made little attempt to provide treatment, families wanted help for their disturbed relatives. Late in the seventeenth century, individuals--not always doctors--converted manors into small hopsitals. For a goodly fee, they offered treatments, and some made extravagant claims.

"In Clerkendale Close ... there is one who, by the blessing of God, cures all lunatic, distracted, or mad people. He seldom exceeds more than three months in the cure of the maddest person that comes in his house. Several have been cured in a fortnight, and some in less time. He has cured several from Bedlam and other madhouses in and about the city." This ad in a London newspaper concludes with "No cure, no money".

Physicians continued to try to understand and cure madness in all its forms. Some of the efforts and changes in succeeding centuries will be discussed in my next post.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Debra Brown is the author of The Companion of Lady Holmeshire.

Her current work is on a novel, For the Skylark, about an emotionally disturbed woman, based on Charles Dickens' Miss Havisham, and her adult twins.

How fascinating! Wow, I didn't know a lot of things about the history of mental illness and it's "cures". How long did the drill in the skull thing go on? Eesh, so many horrible ways to treat mental illness.

ReplyDeleteGreat article, Debra. Really interesting. :)

Diamond @ dee's reads

I enjoyed this. My fifth novel will most probably encompass quite a bit of historical fiction.

ReplyDeleteSo heartbreaking

ReplyDeleteAnd to think that polite society would go to Bethlem Hospital on a weekend or on a holiday, to gawp at the poor inmates and jeer at their discomfort! The treatment of the individuals in the 18th Century involved much scarifying and bleeding, the copious use of emetics to purge the unfortunate creature, and a regime of cold baths. Enough to make anyone mad....

ReplyDelete