by Deborah Swift

|

| Jan Steen - Peasants Before an Inn |

"There is no

place in the world where passengers may so freely command, as in the English inns,

and are attended for themselves and their horses as well as if they were home and

perhaps better, each servant being ready at call, in hope of a small reward in

the morning. Neither did I ever see inns so well furnished with household

stuff" Fynes Moryson 1617*

In the seventeenth century, the coaching inn, sometimes

called a coaching house or staging inn, was a vital hub of travel

anywhere in England. Coaching inns were used to stable and feed the

teams of horses necessary for stagecoaches and mail

coaches, always having a fresh team ready so that travellers could soon be on

their way again. Traditionally, inns were seven miles apart, but

obviously in rural areas they could be

few and far between, whereas in the city, and on popular routes, they would be

far closer together. The stagecoach developed for fare-paying passengers, whereas

previously, the coach was the personal conveyance of aristocrats and the gentry. The

first ever stagecoach route, from Edinburgh to Leith, began in 1610.

Road conditions were generally terrible (see this post on the state of the roads in rthe 17thC)) and because

the countryside was unmarked a traveller would sometimes hire a guide "one guide will serve the whole

company, though many ride together, may easily bring back the horses, driving

them before him, who knows a way as well as a beggar knows his dish"

|

| Painiting by Frank Moss Bennett |

In other words, sometimes the guide would drive extra horses

with the party, so they could be changed, and then he would return the ‘used’

horses to the previous staging post. The most rapid way to travel then was by

means of post-horses, relays of which stood ready at fixed stages. The authorities

had fixed the cost of post-horse hire at 2 1/2d a mile with sixpence for a

mounted post boy who brought back the hired horse. From stage to stage, ten miles an hour was not uncommon. When the roads were in good condition and you were provided with fresh horses, anything from seven to more than a hundred miles could be accomplished in one day. This why when people ask how long it takes to travel from a to b in the 17th century, the answers can be so variable.

|

| Bath Stagecoach map |

In 1639 Captain Bailey, formally a sea captain, erected a

hackney coach stand near the Maypole in the Strand. This new idea was the

equivalent of our taxi service. Seeing its success, other coach drivers soon

flocked to the same place so that;

‘sometimes there is 20

of them together, which disperse up and down, that they and others are to be

had everywhere, as watermen are to be had by the waterside. Everybody is much

pleased with it all; whereas before coaches could not be had but at great rates;

now a man may have one much cheaper.’ Letter from Mr Garrard to Wentworth, London 1639

Travellers depended on the inns if they were going on a long

journey, whether they were in a coach or the newly invented hackney carriage

the horses still needed to rest. Some towns, such as Barnet in

Hertfordshire, on The Great North Road, boasted as many as ten staging inns and

the competition between them was intense, not only for the income from the

stagecoach operators, but because of the profit made by charging passengers for

accommodation and food.

|

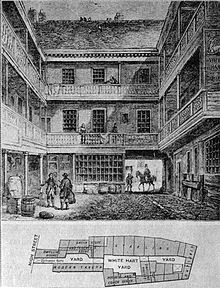

| the old White Hart Inn, Southwark |

London was very well supplied with inns, and at the

beginning of the 17th century the largest, most famous one was the White Hart in Southwark. It had been established in the medieval period and is

even mentioned by Shakespeare in Henry VI, Part II as the

headquarters of the rebels of the Kentish rebellion. It also became one

of the many famous stage posts in the days of Charles Dickens.

Unfortunately it was demolished and rebuilt in the Victorian era.

Walking was the cheapest and most common means of travel,

though it was safer on horseback or in a coach. Hounslow Heath and Shooters

Hill near Blackheath were notorious places for highway thieves, so after a day

travelling on terrible roads and in fear for your life, the inn was no doubt a very welcome sight.

Once at the inn, men of quality were divided from men of

inferior rank. Gentlemen could rent chambers and usually ate alone, unless they

brought their friends or their female ‘consorts’. When I say alone, obviously

gentlemen would have one or two servants attending, and the bill for the night

might be five or six shillings for supper, bed, and breakfast. A solo traveller might

get away with two shillings. Solo travellers would eat communally at the host’s

table and be charged sixpence.

At his inn in St Martins Lane in London in 1695 Thomas Brockbank had ‘sack, mutton

stakes and pigeons’ for his supper, and for breakfast ‘toast and ale.’ Of course the horses fodder would also be charged to you,

eighteen pence in winter for oats, hay and the bedding straw. In summer horses

would be put out to pasture for threepence. (facts from Moryson’s Itinerary 1617)

|

| detail from interior of a Tavern, Jan Steen |

The bed you slept on was likely to be a simple box bed, shared with your travelling companions, and in the same room as your servants. Poorer people would share two or three to a bed with strangers, sharing the tally for the bed, and because it gave warmth in winter when a fire in the hearth cost extra. There was little space for privacy. The mattresses were often filled with pea-shucks, straw, or, if you were lucky, feathers. Inn beds could also be crawling with parasites. The diarist, John Evelyn, used another person’s bed when travelling, without changing the sheets because he was ‘heavy with pain and drowsiness.’ The next day, he wrote; ‘I shortly after paid dearly for my impatience, falling sick of the smallpox.’

Many wealthy people carried their own bed with them, and these could be elaborate affairs. Anne Clifford in her diary recounts how she travelled with her own bed. Having a travelling bed reduced the risk of infection. This great little article from Lancaster University about 17th century sleeping says: 'Stockport Heritage Service owns a travelling box bed, from approximately 1600. This bed was made with a set of stairs (in order to climb into the bed), with two locking wig boxes (again, indicating a relative degree of wealth) and two carved depictions of a husband and wife, complete with initials, fixed to the front of the bed. The panels indicate that this was made to commemorate a wedding and probably given as a gift to the husband and wife.'

As well as choosing an inn, it was possible to stop and

refresh yourself at an alehouse. Alehouses generally did not provide stabling

or accommodation, and were often one-man, or one-woman enterprises, selling from the doorstep. Donald Lupton in 1642 observed that ‘kerb appeal’ was

important for an alehouse: ‘if the houses have a box-bush or an old post,

it is enough to show their profession. But if they be graced with a sign

complete, it's a sign of good custom’. Interestingly, he also tells us that

in these houses "you shall see the

history of Judith, Susanna, Daniel in the Lion's Den, or Dives and Lazarus

painted upon the wall.' So biblical murals are also a sign of a respectable

establishment!

Unlike the coaching inns, with their gentrified clientele, the

alewife must ‘Be courteous to all, though

not by nature yet by her profession, for she must entertain all good and bad;

tag and rag, cut and long-tail. She

suspects tinkers and poor soldiers most; not they will not drink soundly, but

that they will not pay lustily.’

Bibliography

Every One a Witness in the Stuart Age - A F Scott

Suart England - Blair Worden

Young Mr Pepys - John Hearsey

Voices from the World of Samuel Pepys - Jonathan Bastable

Roads in Tring Hertfordshire

Pictures from wiki commons

*Fynes Moryson was educated at Cambridge, and after graduating From May 1591 to May 1595 he travelled round Continental Europe for the specific purpose of observing local customs, institutions, and economics. In 1617, Moryson published the first three volumes of An Itinerary: Containing His Ten Years Travel through the Twelve Dominions of Germany, Bohemia, Switzerland, Netherland, Denmark, Poland, Italy, Turkey, France, England, Scotland and Ireland.

Deborah Swift is the author of three novels set in the 17th Century, and a teenage trilogy. She also writes WWII fiction under pen-name Davina Blake. Find her on Facebook, or twitter @swiftstory, or visit her historical fiction blog.

Great article -fascinating to think of the atmosphere of the old inns - especially if the players were staging a performance. Thanks for the detailed info and biblio!

ReplyDeleteThank goodness we can expect better roads and clean bed linens today! I don't think our own bed will fit in the carry on as we fly to the UK next week. How timely to see this article just as HNS is coming up. We plan to stay in a number of inns and B&B's, and will keep a log for comparison to the ones mentioned here! Really enjoyed this post, Deborah. Thanks so much for the research and insights. Good point about the staging, Elizabeth!

DeleteEnjoy your trip Sally, hope you don't need to bring your own bed!

DeleteJohn Evelyn -- that's a name that rings a bell. I've read about his travels in Spain. I had no idea he caught smallpox in an inn.

ReplyDeleteA great post. Thank you.

ReplyDeleteThanks for your comments everyone. It was a great topic to research.

ReplyDelete