The pass of Dunmail Raise connects Grasmere and Thirlmere, and it’s said that the cairn on the roadside there is the burial place of Dunmail, last king of the Cumbrians, killed in battle in 945. It recently occurred to me, that having a history degree, and being the author of two novels set in the 10thc, I ought to know about said battle. And yet I didn’t.

I set off to find out about Dunmail, and his father, Owain the Giant.

The Giant's Grave

First stop - the Giant’s Grave at St Andrew’s Church in Penrith, purportedly the final resting place of Owain. I was hoping to find some literature about the grave, but a lovely young couple was getting married when I arrived, and I reached my first ‘dead-end’ on the trail. So I moved off in search of Tarn Wadling, on the High Hesket to Armathwaite road. Legend has it that, nearby, Owain the Giant cast a spell on King Arthur. There was bound to be a clue here, surely? Well, after asking several people and being attacked by a swarm of horse-flies, I eventually found Tarn Wadling Wood, but of the tarn itself, long-since drained, there was no visible trace.

Inside Tarn Wadling Wood

Then it was on to the famous Dunmail Raise. That cairn looks suspiciously modern, to me, but never mind. I decided to test out another bit of the legend, which is that two of the slain Dunmail’s warriors carried his crown to Grisedale Tarn and threw it in the water, running to escape the approaching army. Hmm. Have you tried running up to Grisedale Tarn? (Admittedly, I’m no fell runner, nor am I a seasoned medieval warrior!) I will say that the capricious Cumbrian weather provided me with a mystical moment; it was a misty, mizzly morning and by the time I’d climbed up to where the landscape flattens out a little, I could only see about 20ft ahead. I’d no idea how close I was to the water, until the clag suddenly lifted and the tarn appeared, right in front of me. Unfortunately, though there was a sudden beam of sunlight, no hand rose out of the water brandishing Dunmail’s crown.

The 'clag' lifts

So it was now a question of hitting the books and historical sources. Let’s deal with Owain first: what we do know is that he was King Owen of Strathclyde from c.925-37 and was present at Eamont Bridge when the Scots agreed to stop supporting the Vikings against the English kings of Wessex. He broke that treaty in 934, and again at the Battle of Brunanburh in 937. There’s no further mention of him so it’s possible, even likely, that he perished in that battle.

Sometimes he’s called King of Strathclyde, sometimes King of the Cumbrians. Debate continues as to whether those two names were completely interchangeable. But if there’s a distinction to be drawn, it might prove useful later in this search.

Next on the book trail was Dunmail, and I started by looking in Gamble’s Lake District Place-Names. “Dunmail Raise: here, according to tradition, is the grave of Dunmail, one of the last kings of Strathclyde, allegedly killed in battle against Edmund, King of the Saxons in 945. In fact, Dunmail survived the battle and died in Rome 30 years later." (My italics).

Well, I remembered this chap, from my second novel, which features a scene in which King Edgar is rowed along the River Dee at Chester in 973 and paid homage by 6-8 kings. One of them, Donald (Dyfnwal), took his leave to abdicate and go on pilgrimage to Rome. I’ll come back to that later ...

So, where did these ‘rumours’ start? Roger of Wendover, writing in the 13thc, says: (AD 946) “King Edmund ... ravaged the whole of Cumberland, and put out the eyes of the two sons of Dunmail, king of that province.”

Richard Oram, a specialist on Scottish medieval history says, “Certainly, Dyfnwal (Dunmail) is reported to have travelled to Rome, where he became a priest and died in 975. The background to his resignation in 973 may have been the killing in 971 of Cullen, king of the Scots, by Rhydderch, son of King Dyfnwal.”

Something didn’t quite add up. Let’s go back to that ship on the Dee and try to find out who was on it.

You’ll remember I mentioned that there were 6-8 kings; nobody can be sure of the number, nor who was there. The historian Sir Frank Stenton identified, among others,

Malcolm of Strathclyde (975-97) and Dufnal (Dyfnwal/Dunmail), his father, and Roger of Wendover names Malcolm of the Cumbrians, but no Dyfnwal/Dunmail. John of Worcester, writing in the 12thc, named Malcolm ‘rex Cumbrorum’ and “five others” - among them, Dufnal.

So, even though not all the sources say that Dufnal/Dunmail was there, they all agree that Malcolm, his son, was. So, if Dunmail’s sons were blinded to stop them claiming the throne, how come one of them managed to kill Cullen in a revenge attack, and the other ended up being recognised as a king?

I’d come to the end of the trail; Dunmail was not killed in any battle, nor were his sons blinded. He retired to go on pilgrimage and died 30 years after the supposed battle commemorated at Dunmail Raise. The legend had no basis whatsoever.

Near the top of the rise

Still, I wanted to check one more source, a book mentioned by one of the other authors as having some information which might be relevant. It was Phythian-Adam’s Land of the Cumbrians.

In it I found: “Dunmail/Dyfnwal/Donald - possibly the son of Owain, and the king of the Cumbrians who escorted Saint Catroe in c.941 ... dispossessed in 945 of Cumberland by Edmund who blinded two of his sons in order to destroy their claims to the throne ... Described variously as both king of the Britons and king of Strathclyde in 975 when he died on pilgrimage, he rowed Edgar on the Dee in 973 as a king on the same occasion as his son Malcolm was described specifically as King of the Cumbrians.”

Well, that seemed to confirm everything I’d managed to discover. But, who was Saint Catroe? If I could find him, then I could perhaps find a direct reference to Dunmail in 941, just four years before he was supposedly killed in battle and his crown thrown into the tarn.

I found the link. Saint Catroe was persuaded by visions to go on pilgrimage and was escorted part of the way by his cousin, Dunmail/Donald, son of Áed. What? Not the son of Owen/Owain?

I found the answer in my Dictionary of Dark Age Britain: two entries, one atop the other:

Donald, son of Áed, (king c. 940-3) is Dunmail, Catroe’s kinsman, whose sons were blinded.

Donald, Owen’s son, (king c. 962-975) whose son Rhydderch slayed Cullen, went to Rome, having abdicated in favour of his other son, Malcolm.

So there were, in fact, two Dunmails. And that is where we should leave it. Because, it just might mean that our Dunmail did not, after all, die on pilgrimage, but sleeps in his cairn, ready one day to rise up again …

The cairn at the foot of Dunmail Raise

(All photographs property of the author. Illustration - public domain)

~~~~~~~~~~

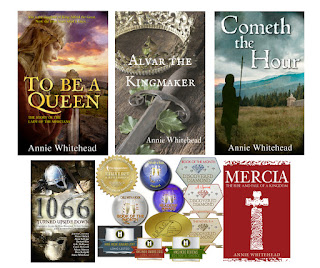

Annie Whitehead is an author and historian, and a member of the Royal Historical Society. She has written three award-winning novels set in Anglo-Saxon Mercia. Her history of Mercia, from Penda the pagan king to the last brave stand of the earl of Mercia against the Conqueror, Mercia: The Rise and Fall of a Kingdom, will be published by Amberley on 15 September

2018.

Buy Alvar the Kingmaker

Buy To Be A Queen

A version of this article originally appeared in the April 2016 issue of Cumbria Magazine

Read a Blog piece about what went on behind the scenes during the research for this article.

Fascinating stuff by a skilled historian and detective!

ReplyDeleteThank you! I had a lot of fun tracking him down - although my fell-walking skills need some polishing :)

ReplyDeleteI had this kink saved and was going through them and was fascinated by your article Annie. Brilliant stuff. I love the mystical Britons.

ReplyDeleteThanks very much, Paula - I'm glad you enjoyed it :)

Delete