In the shadow of Saint Paul's Cathedral, between the London headquarters of British Telecommunications and the American bank, Merrill Lynch, the bombed-out remains of a Wren church have been converted into a pleasant garden, little-visited by tourists, but popular with city workers as a place to eat their sandwiches or sushi at lunch-time. There are few clues to the fact that the second largest church in Medieval London once stood here, or that it was, from 1225 to 1538, the intellectual powerhouse of this great European city.

|

| Christchurch Greyfriars. Photo: Gryffindor (licensed under CCA). |

Friars of the newly created Franciscan Order first arrived in England in 1224. Saint Francis of Assisi was to die in 1226, so it is an intriguing thought that, among their number, there may well have been individuals who had actually known him. A wealthy London businessman, John Iwyn, made a grant of land in the north-western corner of the city to enable them to found a friary. Within a few generations, the establishment was flourishing, with the help of royal patronage: both Queen Margaret, the second wife of Edward I, and Queen Isabella, the wife of Edward II, endowed it, and were buried in its church. Although it was not, in the strictest definitional sense, a university, it was an important seat of learning, with a library to rival those of Oxford and Cambridge.

|

| Plan of Greyfriars in the late 16th Century, from The Greyfriars of London, by Charles Lethbridge Kingsford, 1915 (image is in the Public Domain). |

In the last decade of the 13th Century, a boy named William made his way from Ockham, in Surrey, to London. He may have been as young as nine, or as old as twelve. Perhaps he walked alongside a drover, bringing beasts to the city for slaughter, or he may have hitched a ride on a wagon bringing vegetables or flour to market. He is likely to have carried with him a letter of introduction and recommendation from his parish priest to the Prior of the Franciscans in London. There he entered the order as a novice. He would have studied the scriptures in Latin; Boethius's Consolation of Philosophy (one of the few texts from the classical world to have remained in widespread use throughout the Middle Ages); and Peter Lombard's (1150) Sentences, a standard primer of theology.

By the age of twenty, William of Ockham was an ordained priest. He was himself teaching at Greyfriars, and writing his own commentaries on the works he had studied. In 1309, at the age of twenty-four, he moved to Oxford, where he would have studied the works of Saint Augustine and Thomas Aquinas, and the philosophy of Aristotle, recently translated into Latin by scholars such as Gerard of Cremona, James of Venice, and William of Moerbeke.

|

| Merton College, Oxford, Mob Quad. Built between 1288 and 1378, William of Ockham would have known it as a building site. Photo: DWR (licensed under CCA). |

At Oxford, however, William also learned some hard lessons. Men who served the Church in Holy Orders did not always keep themselves above the insults and back-biting of institutional politics. John Lutterell, the deeply unpopular Dominican Chancellor of Oxford, may have been jealous of William's superior learning, or of the affection in which he was held by his students. Despite fulfilling all the requirements for a masters degree, Lutterell saw to it that he was never promoted above the rank of Inceptor (the lowest teaching grade). When Lutterell was chased from Oxford by his own faculty members in 1322, he sought refuge with Pope John XXII in Avignon, and persuaded the pontiff to summon William of Ockham to answer charges of heresy.

William arrived at Avignon in 1324, and soon found himself in good company. Arraigned with him before a Papal court were Michael of Cesena, the head of the Franciscan Order; Marsilius of Padua; and other leading Franciscans. Lutterell's specific indictments of William were ill-founded, and swiftly dismissed; but there were genuine and significant doctrinal differences between John XXII and the Franciscans. The latter, with William's active and vociferous support, insisted on the doctrine of "Apostolic Poverty" that lay at the centre of their founder's view of the Catholic Faith. Christ and his apostles, they argued, had owned absolutely nothing, in stark contrast to the Pope, who was living like a prince in his palace, paid for by the sale of indulgences which had no basis in scripture. The Pope excommunicated Michael, William and Marsilius, and held them under house arrest in Avignon.

|

| The Palace of the Popes at Avignon. Photo: Jean-Marc Rosier - www.rosier.pro - (licensed under CCA). |

In 1328, almost certainly with the connivance of agents loyal to the Holy Roman Emperor, Louis (or Ludwig) IV, they escaped, making their way first to Pisa, and thence to Louis' court at Munich, where they lived out their days (William died in 1347, not, as is sometimes claimed, of the Black Death, but some months prior to its arrival in the city). Louis, who had his own disputes with the Pope over the relationship between religious and secular power, was only too happy to give them his patronage and allow them to continue writing and teaching at his court. Since Latin was the universal language of academic instruction and debate across Catholic Europe, William could as easily teach and write in London or Oxford, Avignon or Munich: the boy whose father may have been a peasant, or a yeoman farmer, in a Surrey village operated within a single academic network that extended from Portugal to Austria, and from Norway to Sicily.

|

| The Alter Hof, Munich, the centre of Louis' court, reconstructed following destruction during the Second World War. Photo: Robert Theml (licensed under GNU). |

William of Ockham may not be a household name today, but some of his ideas remain highly influential. In Munich, he wrote of the need to separate spiritual rule from earthly rule: kings, he insisted, ought not to interfere in the life of the church; and nor should popes or bishops interfere in the administration of states. Earthly power devolved from God to rulers, not via spiritual intermediaries, but via the people, whose right it was to remove unjust rulers. It was an idea that suited his imperial patron, but it is also the basis for the social contracts, and the separation of church and state, that underlie many of today's democratic constitutions.

He is best remembered, however, for an idea that he formulated in his early teaching days at London Greyfriars. William of Ockham never owned a razor, although, as a tonsured friar, he must surely have used one (the distinction between "ownership" and "right to use" was central to his understanding of his Franciscan vocation). That razor, if it still exists, probably lies buried somewhere in the vicinity of Newgate Street.

|

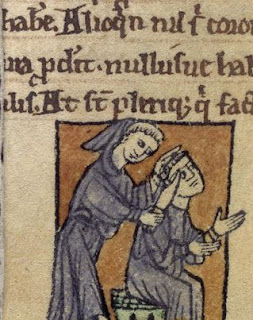

| A monk or friar tonsuring the head of another (image is in the Public Domain). |

"Nunquam ponenda est pluralitas sine necessitate," he wrote, in his commentary on Peter Lombard's Sentences ("plurality must never be posited without necessity"). It was not a wholly original thought (versions of it can be found in the works of earlier theologians, including Thomas Aquinas), but it is as "Occam's Razor" (an analogy that he never used) that it has entered modern thought. In simple terms, "never invoke more variables (or more complex variables) than are actually required to explain a set of facts." It was used by Copernicus to insist on his preference for a heliocentric over a geocentric model of planetary movements (it was possible to believe in either model, but the heliocentric model required only seven variables, the geocentric many more), but it is as useful to the historian as it is to the astronomer. It is our ultimate weapon against extravagant theories, such as Erich von Daniken's sensational notion that the pyramids of Egypt were built by extra-terrestrials; but, perhaps more importantly, against pernicious conspiracy theories directed against particular groups in society, from Anti-Semitic "blood libels," to Holocaust Denial, and fear of a Masonic "New World Order."

Mark Patton blogs regularly on aspects of history and historical fiction at http://mark-patton.blogspot.co.uk. His novels, Undreamed Shores, An Accidental King, and Omphalos, are published by Crooked Cat Publications, and can be purchased from Amazon.

Excellent article. Thank you!

ReplyDeleteBrilliant! Thank you, indeed.

ReplyDeleteWhat an interesting article, Mark - thank you! Do we know whether those three Franciscans - and so presumably many more - were recieved back into the Church? Excommunication was such a horiffic sentence!

ReplyDeleteThere were many more than three, but they were rehabilitated, even if, in some cases, post-mortem. None of them were canonised by the Roman Catholic Church, but William has an Anglican feast-day: English Protestants thought highly of him, but this doesn't seem to have influenced Thomas Cromwell when he dissolved the friary.

DeleteI've walked past that church so often and not known its story. Thank you.

ReplyDelete