by Sam Thomas

When we think about the difference between the past and present, our minds often turn to medicine, and with good reason. Who in their right minds would want to return to a world of leeches and blood-letting, of pregnancy without doctors and high death-rates for both mothers and children? But as so many of the writers on this blog have made clear, there is far more behind the history than modern stereotypes, and childbirth is no exception.

If you were to peek in on a woman in labor (or “in travail” as she might have said), the first thing you might notice is the people in the room. There would be a midwife rather than a doctor, of course, and you’d not find her husband – until the eighteenth century at the very earliest, childbirth was the business of women.

Rather than doctors, nurses, and bright lights, the mother would be surrounded by her female friends and neighbors – her god-sibs or gossips – who came to help, socialize, to see and be seen, and at a more general level, just to make sure that everything went right. (Before we join hands and start to sing Kumbaya, it’s worth noting that sometimes gossips argued with each other, with the midwife, and even with the mother. Imagine if your own mother were present – and giving you advice – when you were in labor.)

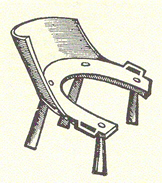

Unlike today, when most women deliver while lying on their backs (good for the doctor, not so good for the mother), early modern women gave birth in a more upright position, either held by two of her gossips or sitting on a birthing stool, or both. While other women could participate in the delivery of the child, only the midwife had the right to touch the mother’s ‘privities.’ Once the child was born, the midwife would cut the umbilical cord (for boys, the longer the cord, the longer his, um, equipment; for girls the shorter the cord, the tighter her privities), swaddle the child, and hand her over to the mother.

The question of maternal mortality has been much discussed, and our best guess is that 5-7% of births ended in the death of the mother. In some cases, death might be caused by an obstructed birth, but more often mothers died some weeks after delivery, usually of puerperal fever, a bacterial infection contracted during childbirth. Thus while individual incidents of maternal death were not terribly common, most women would know a woman who had died in labor.

After giving birth, the mother would enjoy a period of lying-in. During these forty days, she would be confined to her room, free from the demands of household labor. During this time, her neighbors would visit, but she did not go out into public. At the end of her lying-in, the mother would go to her parish church and give thanks to God for her survival, and resume the heavy work of a wife and mother.

----------------

Sam Thomas is the author of The Midwife's Tale: A Mystery from Minotaur/St.Martin's. Want to pre-order a copy? Click here. For more on midwifery and childbirth visit his website. You can also like him on Facebook and follow him on Twitter.

Most interesting. it was tweeted by author Tim Vicary, which is where I came across it.

ReplyDeleteGreat post. I think you might enjoy my book "In Bed with the Tudors" - which started out life as a history of childbirth in Tudor times- it has a facebook page of the same name :)

ReplyDeleteThe absence of men is something of a stereotype. A man or men might be present at any childbed in a crisis -- husband, clergyman, surgeon.

DeleteLooking across Europe as a whole, one can find regions where the presence of the husband was expected, circumstances such as a posthumous birth where male witnesses would be needed to ensure that collateral heirs were not being cheated by the introduction of a suppositious infant, and both medical texts and mother's letters that discuss the value of the husband's presence. We can find men physically and emotionally supporting the mother in difficult births, especially in remote settlements, and even delivering the child as readily as they would deliver a calf or a lamb.

The absence of men was normal and normative, but not universal. There is no easy way to know how often men were present, or in what circumstances, but the assumption of their absence, enforced by the midwife, is based on a limited range of texts and regions.

The presence of mothers might cause problems, especially if they were of a much higher status than the midwife, but even more of a problem, surely, was the presence of women who felt entitled to be present. This might be the woman who lived next door, but had a questionable reputation, or the wife of the local clergyman or gentleman. The belief in a unified women's culture, exemplified by the childbed room, can blind us to the ways in which women could be divided by the same kinds of social, economic, religious or personal conflicts as men were.

As for the risk of death, it was the child that was at risk far more than the mother. Expressions of fear on the part of parents are often quoted, but the mothers are usually expressing fear of infant death. The fathers are more likely to express fear about maternal death and relief, even in the event of infant death despite that being a distressing event, especially if often repeated.

Maternal death is more common in many countries today than it was in England then. Infant death is more common today in communities of the Mississippi Delta region or in many poor countries than it was in England then. How much anguish do readers of this blog feel about that?

Risks can become normalized, just as every rockclimber or motor racer accepts having friends who have died.

As for the forty days of lying-in, this was simply impractical in many households. There was no strong taboo against women re-appearing, so women often returned to their usual roles well before churching, if they were strong enough. Here again, a limited range of normative sources has been taken as universally descriptive.

Great post about "the good old days." I'm curious, though, about the 40-day lying in. Surely peasant and urban poor women couldn't afford that? There were undoubtedly class differences affecting pre- and post-natal care of both mother and babies, no?

ReplyDeleteThank you

ReplyDeleteThis is interesting, and I enjoy learning about history.

Hi Sheila,

ReplyDeleteThat's an excellent point. This is a very middling sort+ image of childbirth, and would be modified as circumstances required. Some poorer women might have gone to their parents' home (if they were still living) which could provide a bit more leeway. But if you're living in a one-room house, there is no delivery room!

The other group I leave out are the women who pregnant illegitimately. For them, childbirth could be an ordeal, as the midwife threatened to walk out if the mother did not reveal the father's name. For unmarried women, the midwife could be a threat rather than a help. (This is important enough that the first birth my midwife attends is of an unmarried woman.)

Sheila, I found some wonderful examples of lower class women giving birth, in the local county court records (in England)- tales of poor beggar women giving birth in barns and staying there for a week before being moved on or servants giving birth at the roadside and in church porches- usually passing women took pity on them and assisted at the labour then carried them to the house of a local priest. Servants often just gave birth in their master's homes, whenever their labour began- sadly these usually show up in case records of infanticide. Others lay low in outbuildings for a few days before abandoning their babies. Their stories are so poignant and full of such tragedy but I prefer them to the formal lyings-in of Queens.

ReplyDeleteSam, sorry to hijack Sheila's point- it's a particular area of interest for me.

ReplyDeleteI have accidentally atached my comment as a reply to Amy Licence. Perhaps it could be moved.

ReplyDeleteNo problem, Amy! I've read a lot of the same documents and you're spot-on!

ReplyDeleteThose who weren't married often concealed the pregnancy and the birth. A favorite way of infantcide was to toss it down the privy. If it were discovered, the woman would say she didn't know she was pregnant or else she didn't know she was giving birth, she just felt the need to use the privy. If a woman was charged with killing her infant, the amount of secrecy attending ther pregnancy and birth played a large part in the verdict. Whether the woman had gathered baby clothes or made arrangements to have the child baptised, also counted.

ReplyDeleteParish committees often had poor pregnant women taken outside of the parish boundaries or tried to send her back to the parish where she was born. It was not very likely that a woman having a baby out of wedlock would call for a midwife.

Good article and fascinating comments, too. I've been meaning to add a page on childbirth to The Compendium of Common Knowledge (ad1558.com) and this may just give me the spur I've been needing. Thanks!

ReplyDeleteHi Anonymous,

ReplyDeleteGood points, but I think we can parse this even further! I spent a lot of time reading bastardy depositions in Chester (who knows if they are representative!) and found an intriguing difference among them. In cases in which a girl or woman had been raped or had slept with a man after being betrothed (a common practice), she seemed to have the sympathy of her neighbors as they attended her in childbirth as they would a married woman.

In contrast, if a woman were seen as promiscuous, she could look forward to very harsh treatment from the midwife and few women would do her the honor of attending her in labor. All bastard-bearers were not seen in the same light!

Very interesting post....:)

ReplyDelete