|

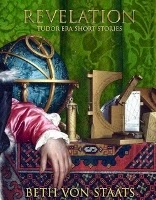

| Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, by Gerlach Flicke |

________________________________________

I take thee to my wedded wife, to have and to hold from this day forward, for better, for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness, and in health, to love and to cherish, till death us depart.

- Archbishop Thomas Cranmer - Book of Common Prayer (1549) -

________________________________________

________________________________________

Although Thomas Cranmer is often considered by historians to be a cautious reformer, his marriage liturgy composed for the Church of England in the Book of Common Prayer introduced a very radical and innovative concept. Beyond the traditional rationals of avoidance of sin and procreation, marriage became for the first time by definition an enjoyable partnership between a man and woman who vowed to "love and cherish" one another.

In our modern era, the thought that God brings people together as kindred spirits and soul mates is embedded in our very societal norms and cultural identity, but in Cranmer's world, his theological stance was revolutionary. Just how did he form his scriptural interpretation of marriage? Many would propose his study of the First Epistle of the Corinthians may have influenced Cranmer's thoughts, but more likely his scriptural studies were personified in his love for two women, a love so profound that he took enormous personal and professional risks uncharacteristic to his highly cautious personality.

Thomas Cranmer certainly was not a priest who kept a mistress as many of his time did. No, this was a man who instead threw to the wayside his vows of clerical celibacy, a practice he came to believe to be a pagan invention, and instead vowed to the women he loved "to love and to cherish, till death us depart", not literally in those words, but certainly in spirit and practice.

Thomas Cranmer's first tragic marriage is a mere footnote to history, a short relationship with a woman named Joan. Cranmer rarely spoke about the marriage, and then only to those he most trusted. The memories were understandably too painful.

In 1515, Cranmer was conferred a Masters Degree in Divinity at Jesus College, Cambridge and was elected to highly sought fellowship. At some point between 1515 and 1519, Cranmer met and married Joan, and in so doing was stripped of his fellowship, along with all affiliation with Jesus College. With no home of his own, Cranmer turned to a family member in Cambridge, a female proprietor of an inn called The Dolphin. There his wife lived, while he worked as a common reader and resided at Buckingham College.

Cranmer's trusted secretary Ralph Morice reported that the marriage ended tragically within a year. Joan, surname unknown but reported to be either Black or Brown at Cranmer's heresy hearings in 1555, died in child bed, along with their baby. This unfortunately all too common 16th century event changed the course of history, altering the course of the impending English Reformation.

Soon after his wife's and child's deaths, Cranmer was readmitted to Jesus College. He subsequently was ordained a priest in 1520. As the years past, Roman Catholic detractors and later Roman Catholic recusants commonly scorned Cranmer's wives to discredit him.

Regarding his first marriage, Cranmer was proclaimed to be an ostler (a caretaker of horses), while the elusive Joan was labeled, "black Joan of the Dolphin". Detractors armed with little detail of the heart-wrenching short marriage painted "black Joan" as a sinful whore, obviously pregnant before marriage.

________________________________________

What the heart loves, the will chooses and the mind justifies.

-- Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury --

What the heart loves, the will chooses and the mind justifies.

-- Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury --

________________________________________

|

| Andreas Osiander, German Lutheran Theologian |

At the time Cranmer arrived in Nuremberg, his theological beliefs very closely aligned with King Henry VIII. Besides a strong belief in the Royal Supremacy, Cranmer was highly humanist in his thinking, heavily influenced by Desiderius Erasmus. Thomas Cranmer's two visits to Nuremberg, however, unleashed a watershed change in Cranmer's religious beliefs, which were heavily influenced through a friendship he developed with Lutheran priest and theologian, Andreas Osiander.

Beyond the religious discussions Cranmer and Osiander enjoyed, which influenced both men's theological development, Andreas Osiander, as well as other Lutheran priests in Nuremberg, was happily married with children. He introduced Cranmer to his niece, Margarete (surname unknown) over dinner.

Soon after, Cranmer did the absolutely unthinkable for a priest working directly in service for the King of England. He ignored his vows of clerical celibacy and married yet again, a Lutheran woman at that. The risks were incalculable. What was the man thinking? Perhaps Cranmer decided it was God's will. If so, he was right. Though the marriage endured years of secrecy and long separation, Thomas Cranmer and his wife begot children and lived openly and by all appearances lovingly upon the ascension of King Edward VI.

Now secretly married, Archdeacon Thomas Cramner continued his services to King Henry VIII through his Ambassadorship to the Holy Roman Emperor, following King Charles through his travels. Given the Holy Roman Empire's ongoing war with the Ottoman Empire, Cranmer's job was a dangerous one indeed. He eloquently updated King Henry VIII, often in cypher, of the horrors he witnessed.

Unknown to Cranmer at the time, William Warham, Archbishop of Canterbury, died August 22, 1532. The death, though not unexpected, provided King Henry VIII, Thomas Cromwell, and the Boleyns with an outstanding opportunity to hand select a new Archbishop like minded to resolving the "King's Great Matter".

Who was their man? Certainly not Bishop Stephen Gardiner, who though highly qualified, recently enraged the King through his defiance over Church liberties. Instead, at the urging of the future Queen of England, King Henry VIII appointed the Boleyn family patroned Archdeacon Cranmer, a move that stunned everyone but those who proposed it. After all, Thomas Cranmer's title of Archdeacon was largely honorary. He never administered a single parish, let alone a diocese.

In October 1532, Cranmer was shocked to learn of his appointment while on assignment in Italy. Commanded to return home immediately to prepare for his consecration as Archbishop of Canterbury, he was left to sort out what steps were needed to safeguard the secrecy of his marriage and more importantly, the safety of his wife.

________________________________________

Those that God hath joined together let no man put asunder.

-- Book of Common Prayer (1549), translated from the Book of Matthew --

________________________________________

________________________________________

|

| Thomas Cranmer's wife depicted hidden in a crate. Julia Wakeham, The Tudors, Showtime |

In December 1543, Thomas Cranmer endured the personal tragedy of his palace at Canterbury being destroyed by fire. One of his brothers-in-law and several of his faithful servants were killed.

Saved from the fire was a precious box owned by the Archbishop, the contents within unknown. This in turn evolved into a story commonly enjoyed and told repeatedly by Roman Catholics during the reigns of Queens Mary and Elizabeth Tudor. Margarete was hiding in that box. Well, of course she was!

Shortly after Thomas Cranmer's martyrdom, detractors published a widely distributed and humorous story weaving a plot where during the reign of King Henry VIII, Cranmer traveled throughout England with his wife, carefully hidden in a large crate with breathing holes. Later versions of the story portray Cranmer anxiously praying for the safe retrieval of a precious wooden crate during the Canterbury Palace fire, the box of course containing "this pretty nobsey". Unfortunately, this is our only hint of Margarete Cranmer's appearance.

In reality, a complete silence enveloped Margarete Cranmer during her stay in England throughout the 1530's. For all intents and purposes, she was invisible. For the politically naive Thomas Cranmer, this was an outstanding accomplishment. In fact, the feat was "astonishing", claims historian Diarmaid MacCulloch. With conservative detractors seeking any way possible to upend him for good, Cranmer's ability to keep his wife and later also his daughter safe speaks to his steadfast commitment to his family and his remarkable resourcefulness.

Unfortunately, even with Thomas Cranmer's great caution, by 1539 it became too dangerous for his wife Margarete and their young daughter Margaret to remain in England. The passage of the Act of Six Articles through Parliament, which included a mandate of strict adherence to clerical celibacy, imposed all married clergy put away their wives. The risk to his family now untenable, he arranged for their exile in Europe. Thus, Thomas Cranmer was separated from his family for the remaining eight long years of King Henry VIII's reign.

Upon the death of King Henry VIII, Archbishop Thomas Cranmer became theologically liberated to craft a Church of England in line with his increasingly Protestant religious beliefs. His first two decisions clearly forecast the sweeping reforms to come. Cranmer began growing a beard, commonly known to be a casting away of Roman Catholicism and papal authority. Far more importantly, he brought his family home.

For the first time since marrying 15 years earlier, Thomas and Margarete Cranmer lived openly as man and wife. An utter astonishment to all those but the very few entrusted through the years, their long kept secret was finally revealed. Unfortunately, they enjoyed a mere five years of family life together before the untimely and premature death of King Edward VI. Soon after, Archbishop Cranmer was arrested by Queen Mary Tudor. His fate sealed, Cranmer's separation from Margarete and his two children, the youngest less than five years old, was permanent.

Thomas Cranmer's arrest, imprisonment and eventual execution a foregone conclusion, some sources propose that with the help of friends in the London printing community, Margarete Cranmer and her daughter escaped the wrath of Queen Mary Tudor and again lived in exile in Europe. Whether reports Margarete fled England are accurate, the London printing community was forefront in her sheltering and protection.

Cranmer's young son, Thomas, was entrusted to the care of his brother, Edmund Cranmer. They too fled with 100% certainty to the Continent. Without the support of his family, and then later colleagues Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley, the Archbishop completely broke down, signing the recantations so damaging to his legacy.

Eventually, after Thomas Cranmer's magnificent final speech and ultimate martyrdom at age 66, the much younger Margarete remarried his close friend and favored publisher, Edward Whitchurch while still in Europe. Upon the ascension of Queen Elizabeth Tudor, the couple settled down with her daughter of Thomas Cranmer in Surrey.

Widowed once more, Margarete married yet again, this time to Bartholomew Scott. Some historical sources claim that Scott married Margarete solely for her money, so she reportedly left him, seeking refuge with Thomas Cranmer's close friend Reyner Wolfe, yet another London printer who hailed originally from the Netherlands, and his wife.

Margarete Scott, widow of Thomas Cranmer, England's first Protestant Archbishop of Canterbury, died on a date lost to history during the 1570's. Unfortunately for us all, her legacy to the nation is unknown but to her family, those who knew her and God.

____________________________

SOURCES:

Author Unidentified, Thomas Cranmer (1489 - 1556), Luminarium: Anthology of English Literature

Author Unidentified, Thomas Cranmer (Archbishop of Canterbury), tudorplace.com.

Foxe, John, "The Life, State, and Story of the Reverend Pastor and Prelate, Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury", Foxe's Book of Martyrs

MacCulloch, Diarmaid, Thomas Cranmer, A Life, Yale University Press, 1996.

____________________________

Beth von Staats is a short story historical fiction writer and administrator of

____________________________

.jpg)