Nearly one thousand years ago*, in November 1016, Cnut became king of England. How did he establish himself, a foreigner, with full authority?

For a contemporary account of the reign of Aethelred II, it is natural to look to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. In it, we find the closing years of the reign fraught with difficulties; those of fending off Danish raiders. It would be easy to agree with the Chronicler who, writing with hindsight, concludes that the slide towards Danish rule in England was inevitable. The payment of the Danegeld might at first sight seem like sheer folly, yet the policy appears in the short term to have worked.

Aethelred’s problem was that paying off one Viking force would not necessarily keep another one away from his shores. The Chronicler blames the military failure of the English on the cowardice of the military leaders. But while the squabble between Brihtric and Wulfnoth caused the loss of a hundred ships in 1009, we also know that Brihtnoth’s actions at the Battle of Maldon in 991 were those of courage and loyalty, that the army of 1009 left in 1010 without tribute, and that Aethelred was assured of the loyalty of Ulfcytel in East Anglia.

King Aethelred II

If things were not as bad before 1009 as the Chronicler would have us believe, there is little doubt that the armies of Swein Forkbeard (Cnut's father) widened any existing cracks in the morale of the English. Within a year, Swein had established himself as full king. But with his death in 1014, the Witan (king's council) sent to Normandy for Aethelred, and accepted him back as their king “if he would govern them more justly than before.” In the same year, Aethelred’s ravaging of Lindsey drove Cnut’s forces away. With further hindsight than the Chronicler had to offer, and perhaps with less bias, it is probably fair to say that it was far from inevitable that Cnut would succeed Aethelred as king of the English. We must, therefore, look elsewhere to find the reasons for his ultimate success.

It is hard to find a source which places emphasis on the military prowess of Cnut; most in fact, praise his piety and generosity to the Church. He was driven back to Denmark in 1014, and his reputation as a warrior must have suffered as a result. So his success in England must be attributed to something other than military superiority. While it might be rash to say that luck was on Cnut’s side, there is no doubt that circumstances helped him a great deal.

King Cnut

Before he left Denmark, Cnut was allowed by his brother King Harald to raise an army. He was fortunate to have the support of Eric of Hlathir, who had played a great part in the overthrow of Olaf Tryggvason, and who was to prove invaluable to Cnut in England. Before Cnut set sail, he was joined by Thorkell the Tall**. It is possible that Thorkell was seeking revenge for the death of his brother at the hands of the English, although it is possible, but not universally accepted among historians, that this revenge was sought earlier, and was, in fact, the reason for Thorkell’s invasion of England in 1009. Whatever his reason, Thorkell’s presence was a bonus for Cnut; he now had with him an accomplished warrior who knew England and the English.

The champion of English resistance was Aethelred’s son, Edmund Ironside. He had procured the support of the Danelaw by marrying the widow of Sigeferth, murdered by Eadric Streona (ealdorman of Mercia) probably at the behest of Aethelred. Cnut could not, therefore, be certain that the Danes in England would submit to him, and he landed in the south and began ravaging Wessex. Edmund and Eadric were raising forces, but they separated before they met the enemy. Eadric joined Cnut, and within four months Cnut was in firm control of Wessex and had the resources of the Mercian ealdormanry at his command.

Edmund Ironside

Edmund had joined his father in London, and when Aethelred died in 1016 the men of London chose Edmund as his successor. Within a few days of Aethelred’s death, however, a more representative assembly at Southampton swore fealty to Cnut in return for a promise of good government. Cnut was again helped by Eadric Streona’s amazing capacity to vacillate. He went over to Edmund’s side, and then took flight during the definitive Battle of Ashingdon. Cnut, as victor, came to terms with Edmund, and the result was a division of the kingdom. Edmund was given Wessex, and the rest of the country beyond the Thames Cnut took for himself. This was obviously a dangerous situation, in which conflict could easily flare up again. As Stenton pointed out, it imposed a divided allegiance on all those noblemen who held land in both Mercia and Wessex. [1] But circumstances once again favoured Cnut when, less than two months after the Battle of Ashingdon, Edmund Ironside died, and the West Saxons accepted Cnut as their king.

King of all England now, Cnut was by no means secure in his position. Good fortune and opportunity had helped him thus far; now he had to rely on his judgement and ability. He eliminated any chance that Richard of Normandy might support the claims of Aethelred’s children by Emma, by marrying the lady himself. For military rather than administrative reasons he divided the kingdom into four: Wessex he controlled himself, Eadric Streona was appointed to Mercia, East Anglia went to Thorkell, and Eric of Hlathir remained in Northumbria. In the same year, 1017, the atheling Eadwig was exiled and subsequently murdered. The Anglo-Saxon aristocracy also lost at least four of its prominent members, among them Eadric Streona. ('Streona' means 'The Grasper' or the 'Acquisitive' and the name first appeared in Hemming's Cartulary, an 11th-century manuscript, pictured below.)

Cnut set out to win the respect of the English church, and in this he was successful, being fully prepared to accept the traditional responsibility of being an agent of God with the duty to protect his people. He claimed to be occupying a throne to which he had been chosen at Gainsborough in 1014, and at Southampton in 1016. Though in reality much was changed during his reign, Cnut sought to establish himself by emphasising the importance of continuity. There was not such a large scale change in land ownership as was to occur in 1066, nor was there a great change in the personnel within the leadership of the Church. Archbishop Wulfstan drew up Cnut’s lawcodes drawing on those he’d written for Aethelred. The lawcodes themselves stressed continuity; very little in them was new.

Cnut (top centre)

Before the end of 1017, with Eadric Streona dead, and the alliance with Normandy secured, Cnut dismissed his fleet, retaining only forty ships. Its dismissal showed that henceforth he intended to rule as the chosen king of the English. At a council at Oxford it was agreed that the laws of Edgar (Aethelred's father, whose reign of 959 to 975 was already beginning to be looked upon as a golden age) should be observed.

In 1018 the military rule was relaxed. Two earldoms were re-established in Wessex, and in Mercia the earldoms of Herefordshire and Worcestershire were re-established. Stenton says that it was then that Cnut's reign began in earnest. [2] But throughout his reign the presence of the huscarls (housecarls) and the distribution of the heregeld (military tax) to them made it difficult for the English to forget that they were being ruled by a conquering alien king. There is no doubt though that by this point Cnut had established himself, for afterwards he felt sufficiently secure to leave the country in four separate expeditions to the north.

Cnut had invaded a vulnerable country in 1015, a country which was war-torn and weary. There were no clear dividing lines of loyalty; Edmund's army included Danes, Cnut’s included Englishmen. There can be no doubt that Cnut benefited considerably from the untrustworthiness of Eadric Streona, and from the dispersal of Edmund’s army in the Danelaw. For Cnut, the death of Edmund Ironside was nothing short of a blessing. Thereafter, his success rested on the fact that he did not conspicuously behave as a conqueror, stressing the importance of continuity, and keeping to the path that the pious King Edgar had trodden.

King Edgar

This emphasis must have taken attention away from the changes his reign brought about. Keeping his military forces for less than a year Cnut reduced feeling among the English that they were a conquered people. Cnut made good use of his opportunities. By 1018 he had successfully established himself as full king of the English.

[1] Anglo-Saxon England - FM Stenton p387

[2] Op cit p 393

**Some historians, Campbell among them, argue that Thorkell did not join Cnut until 1016/17

Further reading/Bibliography:

The Anglo-Saxon Age - DJV Fisher

The Laws of Cnut & The History of Anglo-Saxon Royal Promises - P Stafford in Anglo-Saxon England 10

Encomium Emmae Reginae - Ed Campbell

The Chronicle of Thietmar of Merseberg EHD

The Sermon of the wolf to the English “ “

King Edgar and the Danelaw - Niels Lund, Med Scand 9

The Diplomas of Aethelred the Unready - Simon Keynes

Wulfstan and the Laws of Cnut - D Whitelock EHR 63

(all the above images are in the public domain)

*This article is an Editor's Choice and was originally published September 19, 2016

~~~~~~~~~~

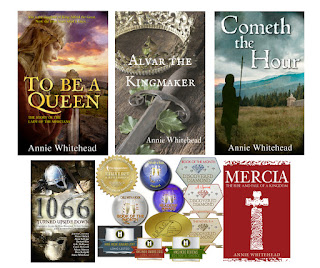

Find out more at www.anniewhiteheadauthor.co.uk