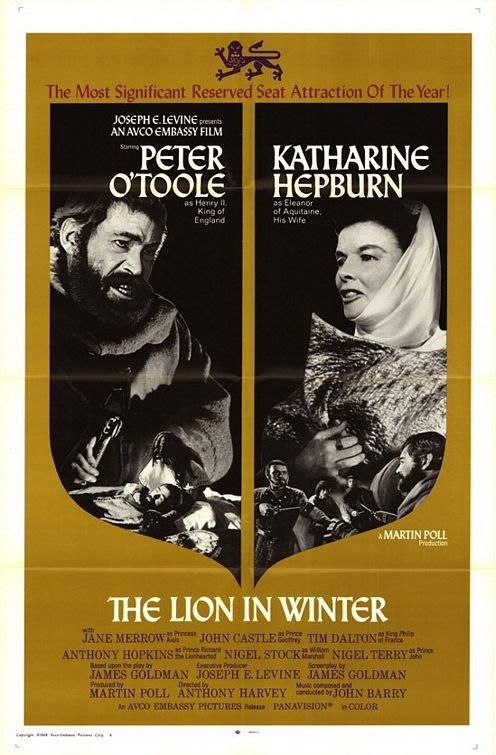

I still remember watching it for the first time. The Lion in Winter. The first historical piece that I encountered which asserted that Richard the Lionheart was a homosexual.

Naturally, I could hardly help wondering whether the portrayal was accurate. What evidence did the playwright and screenwriter James Goldman have for depicting Richard in this manner? Why had none of the history books I had read during my teenage years mentioned it?

Doing a little research, I discovered that no one had seriously mooted the idea that Richard the Lionheart was a homosexual up until the middle of the twentieth century. At this time a case for Richard's homosexuality was made based on these three points:

- He had no children (except for possibly one illegitimate son);

- He didn't seem very interested in getting married (deserting his wife Berengaria right after they tied the knot);

- In his early days, he had a very close relationship with Philip Augustus of France.

When I saw these three points, I had to wonder if the case they made for Richard’s homosexuality was actually a compelling one. I researched a little more….

The first fact, that Richard had no children, is neither here nor there. It does not take a genius to think of other reasons for childlessness than being a homosexual. And in the medieval world, a homosexual king would have likely also been married (to a woman) and fathered children (the kings Edward II and James I come to mind), because no matter what one’s sexual proclivities were, producing an heir and preserving dynastic succession was paramount.

The second assertion, that Richard wasn’t very interested in marriage or in Berengaria, is, if you believe the well-respected novelist Sharon Kay Penman, surprisingly incorrect. In an interview with the Historical Novel Society, Penman said:

Another myth is that Richard was reluctant to wed Berengaria and Eleanor had to push him into it; he was actually the one who negotiated the marriage with Berengaria’s father…. I was surprised to discover that Richard went to some trouble to have her with him during their time in the Holy Land.Although their marriage does not appear to have been one of the world’s greatest love matches, there is no evidence of “reluctance to marry” on Richard’s part, a fact which has been used to bolster the argument for his homosexuality.

|

| Philip Augustus and Richard the Lionheart |

The final piece of evidence used to prove Richard’s homosexuality is his relationship with the French king Philip Augustus. One of the most pertinent primary source excerpts says:

And after this peace, Richard the Count of Poitou remained with the king of France against the will of his father; and the king of France was honoring him in such a way that each day they would eat together at one table from one dish, and in the night their bed did not separate them. And because of this exceeding love which appeared between them, the king of England [Henry II] was struck with much astonishment and marveled at this, and being on his guard for himself in the future, sent his messengers frequently to France to recall his son Richard....So, there you have it. “In the night their bed did not separate them.” But does this text give a homosexual connotation to Richard and Philip sharing a bed? Not really. It seems to be just another way that Philip was honoring Richard. Although my husband would probably object to sharing a bed with another man, we must remember that in the Middle Ages, men (yes, heterosexual men) shared beds all the time.

Some have read into this text that Richard's father Henry is upset about the strange relationship developing between his son Richard and Philip, the King of France. The text clearly shows that he is upset, but it does not seem to be from a fear of homosexual activity. His son Richard is befriending the longtime enemy of England, and Henry is trying to stop them from allying against him.

Judging this quote by the standards of the time it was written in, I think it is fair to say that the author is making no implications, veiled or otherwise, of homosexual relations between Richard and Philip.

So, given what we know about the evidence, was James Goldman within his rights to depict a homosexual relationship between Richard the Lionheart and Philip Augustus? Certainly. His play The Lion in Winter is, after all, a work of historical fiction. But viewers (and readers) must always keep in mind that the historical fiction writer deals with the realm of possibility, and not necessarily the realms of plausibility or probability.

____________________________

Rosanne E. Lortz is the author of two books: I Serve: A Novel of the Black Prince, a historical adventure/romance set during the Hundred Years' War, and Road from the West: Book I of the Chronicles of Tancred, the beginning of a trilogy which takes place during the First Crusade.

You can learn more about Rosanne's books at her Author Website where she also blogs about writing, mothering, and things historical.