by Mark Patton

In an

earlier blog-post, I introduced the topic of Medieval trade between London and Venice. Each year, a fleet of galleys would set sail from Venice, passing through the Straits of Gibraltar, along the Atlantic coasts of Portugal, Spain and France, and into the English Channel, half of them bound for London, the other half for Flanders. They brought with them silk thread and cloth from China and Persia; spices from India; and wine from Italy; and returned with woolen cloth, raw wool; expensive embroideries from London; and tin from the mines of Cornwall. Remarkably, we have a written record from one of the men who sailed on these ships, Michael of Rhodes.

|

| A Flanders Galley, from the Book of Michael of Rhodes (image is in the Public Domain): these vessels were specially built to withstand the storms of the Atlantic. |

Michael was, ethnically, a Greek, and spoke Greek as his first language, although he seems only ever to have been literate in Venetian (his book includes prayers in Greek, presumably remembered from his childhood, but they are transcribed in Latin letters). He joined the Venetian navy as a humble oarsman in 1401, and, over the course of a 44-year career, which saw him sailing to Constantinople, Alexandria, Beirut, London and Bruges, rose through the ranks to be

Nochiero (Midshipman),

Paron (responsible for provisioning, ballasting and stowing of the ship),

Comito (Sailing Master) and

Armirao (effective commander of a fleet, responsible to a nobleman who did not necessarily have the skills of a master-mariner). He served on both commercial and military vessels, and was wounded in action at least once. Further details of his career can be found

here.

Michael's first visit to London was in 1406, when he was a

Proder (a senior oarsman, responsible for discipline on the benches). He would have had an uncomfortable journey, sleeping on his bench, exposed to the elements, and living on a diet of ship's biscuits and broth. Although the ship would have traveled under sail throughout most of her time at sea, Michael and the 180 oarsmen would have had to row her up the Thames. He would have stepped ashore, exhausted, at Galley Quay, close to the Tower of London.

The arrival of a galley signaled the beginning of an unofficial trade fair, since each member of the crew was entitled to a

portata, a small package of goods that he could trade on his own account. This might have included trinkets of glass, pottery or copper made by his relatives in Venice or on Rhodes. If he was lucky, he might have been able to afford a few nights in a real bed (even if shared), and some decent meals washed down with ale.

Michael's second trip to London, in 1443, was under very different circumstances. He was now an experienced master-mariner, and a senior officer, a

Homo de Conseio, selected by a panel chaired by the Doge. In London, he is likely to have been wined and dined by the Lord Mayor, and by the masters of those livery companies whose members traded with the Venetians: the Broderers, Haberdashers, Drapers, Woolmen and Vintners. He is unlikely to have spoken much English, but Venetian traders had permanent offices in London, which would have provided translators.

At sea, his responsibilities seem to have included the training of the

Nochieri, men (some of them of noble birth), who were being prepared for careers as master-mariners. His book is, in large part, a training manual, encompassing ship-building; rigging; navigational and commercial mathematics; and sailing directions for voyages around the Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts. It may have played a role in securing his promotion to a senior post, and he seems to have sold it to another mariner on his retirement, an item of considerable value.

|

| Diagram showing the construction of a ship's hull, from the Book of Michael of Rhodes (image is in the Public Domain). |

|

| A galley under construction, from the Book of Michael of Rhodes (image is in the Public Domain). |

|

| Diagram showing lateen sails, from the Book of Michael of Rhodes (image is in the Public Domain). |

|

| Mathematical calculations, from the Book of Michael of Rhodes (image is in the Public Domain). |

Michael of Rhodes belonged to one of the last generation of mariners who sailed without charts. A draftsman of not inconsiderable talent, his book includes nothing that looks remotely like a map. Although he does not mention a compass, he probably did use one, but he would not have had a sextant, astrolabe or telescope. He would have followed the coastlines, using a

Portolan (a list of landmarks - his book includes several of these, including one for the English Channel), making relatively frequent stops to take on fresh water, and other supplies, and using trigonometry (his book includes the relevant tables) to keep track of his position between anchorages.

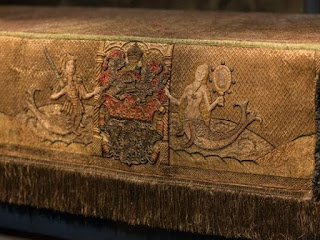

|

| A mock coat of arms gives us a rare insight into Michael's sense of humour. The turnips on either side may refer to the diet on board his ships, whilst the mouse firmly in control of a cat is an appropriate emblem for a man who has risen from humble origins to the top of his trade (image is in the Public Domain). |

Written on paper (cheaper, and lighter, but less durable, than vellum), Michael's book is a remarkable survival. Although in private ownership, it has been extensively studied by academics, and a facsimile has been published, together with a full transcription and translation. It is one of the most important primary sources for anyone wishing to understand navigation, commerce, and applied mathematics in the Late Medieval Age.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Mark Patton blogs regularly on aspects of history and historical fiction at

http://mark-patton.blogspot.co.uk. His novels,

Undreamed Shores,

An Accidental King, and

Omphalos, are published by Crooked Cat Publications and can be purchased from

Amazon.