by Judith Arnopp

The

Luttrell Psalter, written and illuminated in the second quarter of the

fourteenth century, contains the psalms and canticles, a calendar of church

festivals and saint’s days, and a litany with collects and the office of the

dead. A single scribe was responsible for the Latin text which covers three

hundred and nine leaves of vellum but a variety of hands assisted with the

marginal decoration.

The text is of a distinctive square script possibly designed

to be read at a distance and the work is illuminated in a manner undetected in

other contemporary work. The resulting manuscript is testament to the grandeur

of the man who commissioned it and the work remains as strikingly symbolic of

his status today as it was during his lifetime.

The

portrait of Sir Geoffrey Luttrell together with its inscription ‘Dns Galfridus louterell me fieri fecit / The

Lord Geoffrey Luttrell caused me to be made’ ensures that his name and the

splendid Psalter will be forever connected, each gracing the other. The purpose

of the book was to glorify both the life of Christ and that of Sir Geoffrey

Luttrell.

It is not, however, the liturgical content that have made the

manuscript so uniquely famous but the scenes of domesticity and rural idyll

that decorate the borders.

Modern

history books, ranging from primary school histories to treatises on medieval

farming, are often illustrated with scenes from the psalter. It is generally

accepted that the work provides an honest account of fourteenth century life.

Janet Backhouse,

an authority on medieval manuscripts, comments that the Luttrell Psalter is permeated with a ‘general atmosphere of

satisfaction and rejoicing…[1]’ but

close examination shows that this is not necessarily so. The illustrations

of the labourers seem to me to be notable for their marked lack of satisfaction and joy. For all the colourful clothing and

depictions of leisure they still come across as repressed and resentful. In

fact, there is not the slightest suggestion of a smile in the entire manuscript.

The inhabitants

of the margins seem to be acting out an idyll, perhaps more for the sake of the

intended reader than for any attempt to represent reality. Their clothes are

inappropriate both to their station and lifestyle which would have been one of

toil, their role being to provide luxury for the Knight and his family. It is

as if the artist has been instructed to show scenes of idyll (possibly at the

behest of his employer) but has been unable or unwilling to disguise an

underlying dissent.

William

Langland in his poem Piers Plowman depicts similar scenes in his prelude to The Vision of Piers Plowman. He sees the

idyll of the scene before him but is aware of the discord beneath. His poem,

however, is of a vision or a dream, and the idealisation of rural life is more obvious

than in Geoffrey Luttrell’s vision of his country estate.

‘of alle manere men, the mene and the pore,

worschyng and wandryng as this world ascuth.

Somme otte hem to the plogh, playde ful selde,

In settynge and in sowynge swonken ful harde

And wone pat pis wastors with glotony destrueth.

And summe putte hem to pruyde and parayled hem per-aftir

In continence of clothing in many kyne gyse.

In preiers and penaunces potten hem mony,

Al for

love of oure Lord lyuenden swythe harde

In hope to haue a good ende and heuenriche blisse.’

The Luttrell

Psalter was produced at the end of one of the most tumultuous periods in

history; rebellion, civil conflict, failed harvests and famine resulted in a

social chaos that threatened the stability of every social strata, not least

that of the landed classes.

The resulting insecurity meant that the maintenance

of social position, was paramount and the nobility needed to be perceived as

secure in an uncertain world.

The comfort

of the lord of the manor took precedence over those of his tenants; the

freeholder tenants paid a monetary rent to the lord but the servile tenants

were required to pay their dues with labour. The Lord owned the mill (or maybe

more than one) and required every villager to use it and pay the customary fee

which usually took the form of a portion of the milled flour.

This monopoly

caused rancour and gave birth to the stereotypical untrustworthy miller of

contemporary literature. Other capitalist enterprises controlled by the

landowner were fishing, bird snaring, sheep and arable farming; and all of

these activities can be seen in the Luttrell Psalter.

Images of

farming dominate the margins; ploughing, sowing (f.170), weeding and harvesting

(f.172), but how far should we trust these images as being representational of

rural reality? The illustrations may provide evidence of types of tools that

were currently in use, but it remains unlikely that the workers were provided

with such costly attire.

The warm

hoods and protective gloves are more probably a part of Sir Geoffrey’s idlyll. In

medieval England dress was an indication of social status. Sumptuary laws

prohibited anyone below the rank of knight from wearing satin and some limitation

was placed upon the fur and colours he was allowed to wear.

As Michael Camille

confirms, ‘the peasants are being dressed

up to Sir Geoffrey’s level of taste and cosmeticized, much as they are in

Bruegel’s later paintings.[2]’ Other

aspects also suggest that we should be wary

of taking the images too literally, for example the reaping scene (f.172).

This

illustration depicts two women cutting the standing corn while a third eases

her aching back (f.172) and a man binds the cut corn into sheaths. Studies of

almost one hundred medieval images of reaping reveal only one other

illustration of women performing farming work.[3] This

strongly suggests that it was a task largely carried out by men. So, these

images are likely a projection of Sir Geoffrey Luttrell’s ideal world where he

is the centre of an ordered, prosperous society. However, the Psalter’s

illustrations suggest that, actually, the opposite was true.

The

reality is glorified in order to convince those around Geofrey Luttrell of his

unassailable power and virtue.

The idyllic representation magnifies his status

to that of a Christ figure. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the

comparison of the illustration of the Luttrell family at table (Fol. 208v) with

the representation of the Last Supper (Fol. 90v).

The design

and symmetry of the two illustrations are almost exact. Sir Geoffrey sits at

the centre of his family just as Christ sits at the centre of his disciples. He

is the focus of attention and there is even a servant standing to one side waiting

to serve him, just as Judas kneels before Christ.

One

notable difference is that at the table of the Last Supper Jesus is giving

Judas ‘the sop[4]’ whereas

Sir Geoffrey is preparing to drink himself from the cup which he holds in his

right hand.

Michael Camille notes that the cup Sir Geoffrey is holding

illustrates the verse from the accompanying psalm ‘Calicem salutaris accipiam et nomen domini invocabo’ (I will take the

chalice of salvation, and I will call upon the name of the Lord. Psalm 115.13).

Emmerson

and Goldberg state in their paper Lordship

and Labour in the Luttrell Psalter that in their view, ‘the visual allusion to the chalice of salvation and the possible

invocation of the Lord’s name further underscore the eucharistic allusions and

the entire scene’s association with the Last Supper. Such deliberate, and to

our minds, perhaps slightly shocking, juxtaposition of the secular lord with

the Lord is also found elsewhere in the psalter.[5]’

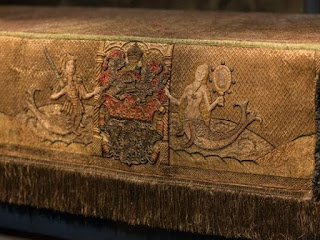

In fact the most lavish illustration in the manuscript is the

portrait of Geoffrey being armed by his wife and daughter in law. The prominent

use of heraldry, which can be observed on his surcoat, shoulders, helmet,

pennon and horse trappings, together with the inscription ‘Dominus Galfridus Louterell me fieri fecit’ all serve

to promote his importance. God created the world, David wrote the psalms and

Sir Geoffrey commissioned the Luttrell Psalter.

The

importance of Sir Geoffrey’s lordship is crucial to the understanding of the

Psalter itself. It is intended as a glorification of his status as the Lord of

his estates, he is depicted as a great knight (although he would have been long

past fighting age when the work was commissioned) and worthy of homage. The

peasants who inhabit his estate spend their lives working for his continued

prosperity and eminence in much the same way that Christians are expected to

live their lives for the greater glory of God. This self-canonisation does not

necessarily denote confidence or stability but rather suggests the opposite;

the impulse to self-aggrandise often springing from insecurity or anxiety.

Many

of the illustrations seem to involve representations of theft or the fear of

loss; for instance the crows that attempt to steal the grain (f.170 and f.171)

or the hawks preying upon the poultry (f.169). The image of the small boy

stealing cherries from the tree described by Janet Backhouse as ‘a lively scene[6]’ is

undoubtedly finely drawn and informative but while Backhouse notes the detail

of the tree bark and clothing she understates the threat of punishment that the

older man’s ‘club’ represents. The

child is stealing cherries that are intended for the Luttrell table and his

punishment may well be severe, another dark undertone to the colourful peasant lifestyle

presented by the artist.

Even the

miller, whose stereotypical untrustworthy nature has been recorded by Chaucer, ‘a theef he was for sothe of corn mele / and

that a sly, and usuant for to stele[7]’(3939)

seems afraid of becoming the victim of theft and has armed himself with a

fierce dog to protect his Lord’s property. These

images of plunder suggest insecurity and fear of loss. One explanation of the proliferation

of these images is that the deprivations of the great famine of 1315 -16 and

the civil war of 1321-22 would have still been fresh in the medieval mind.

The scenes

of farming and food preparation culminate in the feast at the Luttrell table,

the grain provides the flour for the bread, the poultry provides the meat, the

sheep provide the milk and the hens provide the eggs. The

labourers strive to put food, not into the mouths of their

families but into the mouths of the Luttrell family.

The entire ritual of

tilling the soil, sowing the grain, harvesting the crop, milling the flour and

cooking the meal is for the benefit of the Lord while those who labour receive

little or no benefit at all. The back breaking labour of the lower classes is

consumed by the upper; and, just as the seeds of their labour are consumed by

the crows, so are the end results of their toil consumed by the Luttrells.

The mouths

of the labourers in the margins are largely painted as down-turned grimaces

which lend discontent to their expressions. The rowers of the boat are among

those illustrations that depict the open mouth, whether this is meant to depict

horror, surprise or singing is unclear but what is clear is that they are not

representative of joy or contentment. The men in the boat retain their

impassive expressions and subjugated body language, which paired with their

peculiarly open mouths, lends a mask-like appearance to their faces. The open

mouth is extended to include biting and consuming activities elsewhere in the

margins and there is scarcely a page that fails to depict a human or beast

biting another life form or even in some cases biting itself.

Fol. 59v

shows an image of swine feeding on acorns thrown down to them by the swineherd,

Camille interprets this in conjunction with St Bernard’s Sermon which describes

the oak as barren ‘And if they bear fruit

it is not fit for human consumption but for pigs. Such are the children of this

world, living in carousing and drunkeness, in overdrinking and overeating, in

beds and shameless acts.[8]’

St

Apollonia (who stands nearby) wears her teeth on a rosary to illustrate how

they were extracted as part of her torture and martyrdom and her mouth is a

crimson gash across her face. The porcine illustration of gluttony and sexual

excess contrasts sharply with the toothless saint. Teeth, often associated with

hell and vice, are used by the pigs to indulge in that from which St Apollonia

abstains.

The gaping

mouth of hell is represented on fol. 157v and serves as a vivid reminder of the

consequence which waits to consume the ungodly sinner. The unfortunate man who

walks in naked trepidation to his fate looks suitably repentant and illustrates

the futility of earthy sin.

Interestingly,

at the foot of this page is a mysterious illustration that has baffled

historians for some time, Backhouse sees it as ‘an unidentified game of skill[9]’

while the less idealistic Camille views it as ‘water torture.[10]’

The illustration could represent an early drinking game wherein the victim is required to measure the quantity

of ale he can consume. This would fit nicely alongside other representations of

vice and gluttony and also compliment the accompanying representations of death

and descent into hell.

The combined images urge the reader to repent of the sin

of gluttony before it is too late and we must remember that peasants were not

usually in the position to commit that particular sin.

There are clearly more questions raised by

this manuscript than can be answered but what is quite clear is that it is not

representative of the social idyll that Geoffrey Luttrell desired.

Of course,

images of hybrids and grotesques are found elsewhere in medieval art and

architecture, usually in the margins of a civilised space like church or

monastic portals; and it is apparent that they represent some long lost meaning.

Their presence however does emphasise that there is more occurring in this

manuscript than we can as yet, understand and, if we

accept that the grotesques have cryptic connotations then it seems naïve to

accept that any part of the manuscript is truly representative of the

fourteenth century.

There are

many images in the margins that are distinctly separate from the

Luttrell family yet necessary to their continued prosperity. Labourers,

foreigners, grotesques and women are depicted in terms of excess and sin, the

clothes of the lower class women that fly about them denote their sinful state

and can be directly contrasted to the discreet dress of Agnes and Beatrice

Luttrell. Images of greed, lust and sin dominate the margins, juxtaposed with

the devotional doctrine of the Psalms. Monsters and sinners mingle with saints

and martyrs.

There are

many aspects of the Psalter that adhere to Sir Geoffrey’s (apparent) desire for

an idealised representation of life but his perfect world is undermined

by cosseted labourers with surly faces, women carrying out inappropriate tasks,

monks wielding weapons of war, the ever-present consuming mouth, the scenes of

theft. All of these turn Geoffrey Luttrell’s world into one of insecurity and even

dread

In the

words of Michael Camille, ‘Rather than

being a reflection of fourteenth century reality the Luttrell Psalter, like

most important works of art, restructures reality and shores up the conflicts

and discontinuities of late medieval England. It presents its noble owner as an

active knight at a time when not only were his chivalric values outdated but he

could no longer ride a horse. It presents him as the paterfamilias in his hall

and a supporter of his church during the very period when he was faced with

charges of incest and when the nobility was withdrawing into an ever-more

private world at home and in private oratories. It displays his peasants as

idealised labourers during the decades of agricultural crisis. The artists who

made this monument for their patron in the third decade of the fourteenth

century were creating an account of the contradictions of their age.[11]’

The

Psalter provides a cameo of a period when rural England was on the brink of

major agricultural reform; when discontent was present but the means of reform

not yet available, resulting in insecurity and hunger jostling for dominance

over subjugation.

Geoffrey

Luttrell desired to be commemorated and aggrandised in this manuscript but it

is obvious that the scribe had other ideas. The status of a scribe would have

been no higher than that of a ploughman so the artists may have been from the very peasant

class they were requested to depict. Perhaps it was impossible to resist

representing Geoffrey Luttrell’s 'perfect world' from the perspective of the

labouring class from which the illustrator sprung.

The

Luttrell Psalter can viewed online here

Photos property of the British library

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Backhouse, Janet The Luttrell

Psalter (Warwick: The Roundwood Press, 1989)

Camille, Michael. Mirror in Parchment

(Guildford: Reaktion Books Ltd., 1998)

Backhouse, Janet. Medieval Life in the

Luttrell Psalter (Hong Kong: South Sea International Press, 2000)

The Riverside Chaucer, ed. by

Larry D. Benson (Bath: Oxford University

Press, 1988)

The Problem of Labour in Fourteenth

Century England, ed., by J. Bothwell, P.J.P. Goldberg, W.M. Ormrod (Bury St Edmunds: York Medieval Press, 2000)

~~~~~~~~~~~~

Judith Arnopp writes historical fiction. You can find more information on her website: www.juditharnopp.com