Social activities, fashions, entertainment and more are all driven by “the next big thing.” This is nothing new. Throughout history, we can find examples of this. During the Regency era, Almack’s Assembly Rooms were THE place to be during the Regency era. A voucher for Almack’s conveyed more social impact than invitations to multiple private balls and parties. When Almack’s Assembly Rooms opened in February of 1765, Mr. Macall was in direct competition with Mrs. Cornelys’ assemblies at Carlisle House, and it was by no means certain that Almack’s would be “the next big thing”. A veritable Studio 54 of its time, the assemblies at Carlisle House were geared for the highest society and were quite something....

Who was Mrs. Cornelys? Teresa Cornelys, also known as the Empress of Pleasure and the Queen of Masquerades, was born Anna Maria Teresa Imer in Venice in 1723, the daughter of Giuseppe Imer, an opera impresario. Her mother Paolina was an actress. Teresa herself was a singer and dancer. She was described as beautiful, but I found no particulars. She led an extremely interesting life: she was married to a dancer named Angelo Pompeati in Vienna but lived with him only a few months. She became a well-known opera singer, and courtesan; at age 17, she was desired by Senator Alvise Gasparo Malpiero; some sources say she was his mistress. (Malpiero befriended a young Giacomo Casanova, who was frequently at his home.) Teresa fell madly in love with Casanova, who may have been the father of her first child, a son named Giuseppe. Her husband did not acknowledge the child; however, many accounts do not list Giuseppe as Casanova’s son either. She subsequently had a daughter named Wilhelmine by a different lover, a daughter named Sophie by Casanova (most accounts do list Sophie as Casanova’s daughter), and another baby by someone else. Wilhelmine and the baby both died. She had numerous lovers and used multiple names. Despite her own singing career and income from her various lovers, she was jailed for debt in Paris. Casanova took their son to raise in 1759. Teresa and Sophie moved on to the Netherlands.

Teresa had first appeared in London at the Haymarket under the name Madame Pompeati, in an opera by Gluck, in 1746. The reviews were not good, and she returned to the continent. After her release from debtor’s prison, she was convinced to try England again by a wealthy man known as John Freeman (and John Boorder and John Fermor which name he used in England) who she met in Holland and who may have been her lover. Using the name Cornelys (after a lover named Cornelis de Rigorboos in Rotterdam), she presented herself as a widow, and apparently benefited greatly from sympathy for her widowed state as well as the expanded legal rights enjoyed by widows as opposed to single or married women. At this time, she was about 37 years old. When she arrived in London this time, Teresa apparently decided to be a producer instead of an entertainer. In April of 1760, with the financial backing of John Fermor (as he was now known), Teresa rented Carlisle House in Soho Square, which she subsequently purchased a few months later.

At one time the home of the 2nd Earl of Carlisle, Edward Howard, Carlisle House changed hands, and Teresa rented the house and its furnishings for 180 pounds per year from the owner, before she purchased it. She made extensive renovations to the house during her occupancy, adding several rooms (including a supper room and a ballroom/concert hall) which were connected to the original house by a Chinese bridge. She opened her business to provide entertainment to the upper classes by private subscription later in 1760, calling her membership “The Society.” By making her entertainments a subscription affair, she evaded licensing laws in effect at the time as well as making them private and exclusive since not everyone could get tickets and she indicated that the cost was merely to cover expenses. (The Licensing Acts of 1737 and 1752 were in effect at the time, regulating legitimate theatrical entertainment as well as places open for public entertainment in and within 20 miles of London and Westminster.) Initially confined to dancing and card playing, Teresa expanded the entertainments offered to include concerts, balls and masquerades. Her rooms became very popular, and were known as much for their size and beauty of architecture and decoration as for the quality of the entertainments themselves. Musicians of note played and directed the concerts at her rooms, including Johann Christian Bach in 1765. As time went on, her entertainments became known for their sexual overtones, and the rooms were becoming known as a place of secret meetings for sexual purposes.

|

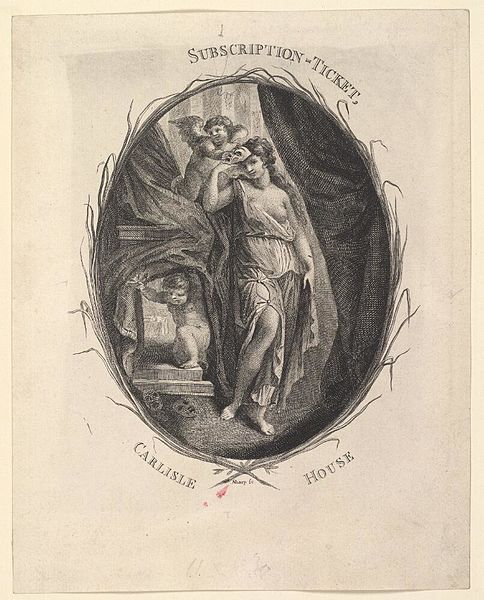

| Subscription ticket for Carlisle House |

Thanks to the support of society friends,

including Lady Elizabeth Chudleigh (who would become a principal in a notorious

bigamy case, having married in 1744 Augustus John Hervey (who became the 3rd

Earl of Bristol) and then married Evelyn Pierpont, the 2nd Duke of

Kingston-upon-Hull in 1769), Mrs. Cornelys’ rooms became THE place to be. In April of 1768, members of the Royal family

and the Prince of Monaco, and

subsequently in August the King of Denmark, attended entertainments at Carlisle

House. The quality of the suppers served

and the elegance of the surroundings (including the light of many wax candles)

all contributed to the popularity of these events as well as to the costs. Teresa showed herself to be a shrewd business

woman, advertising her entertainments shrewdly and maintaining her attendance

for over a decade. However, her business

sense had never included the good management of money. Her continual remodeling costs as well as her

operating costs continued. Even though she increased her subscription

costs for special events, somehow she was never able to get out of debt and

show a profit.

|

| Ticket for Masque Ball at Carlisle House |

Later in 1772, Teresa Cornelys was bankrupt. Her creditors seized Carlisle House and tried to auction off her assets, but did not succeed. It reopened, with different management, in hopes of making a profit. By 1776, Teresa was back in possession of Carlisle House but she could never achieve any level of success and she gave up in 1783, when she or her creditors tried to rent out the house and furnishings. By March of 1784, the house was empty. (Carlisle House was demolished in 1791.) She attempted other ventures under the name of Mrs. Smith that were equally unsuccessful, and she was finally confined in the Fleet Prison for debt. While in prison, Teresa was being treated by Chevalier Bartholomew Ruspini (of questionable medical qualifications who advertised heavily) for a cancerous sore on her breast, but his treatment was unsuccessful. She died in Fleet Prison on August 19, 1797, age 74.

Sources include:

Chancellor, E. Beresford. MEMORIALS OF ST. JAMES’S STREET and CHRONICLES OF ALMACK’S. New York: Brentano’s, 1922.

THE LONDON ENCYCLOPAEDIA 3rd Edition. Ben Weinreb, Christopher Hibbert, Julia Keay and John Keay, authors. London: Macmillan London Ltd., 2008.

Darcytodionysus.com. “Personality of the Month: Teresa Cornelys” posted by Meg McNulty, August 3, 2010. HERE

GoogleBooks. Cruikshank, Dan. LONDON’S SINFUL SECRET:The Bawdy History and Very Public Passions of London’s Georgian Age. “At Home with Mrs. Cornelys.” Pp. 196-202. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2009. (Preview) HERE

GoogleBooks. DICTIONARY OF NATIONAL BIOGRAPHY. Leslie Stephen, ed. Vol. 12. New York: Macmillan and Co., 1887. “Cornelys, Theresa (1723-1797)” by Warwick Wrote. Pp. 223-225. HERE

Googlebooks. THE GENTLEMAN’S MAGAZINE. Vol. 284. January to June 1898. London: Chatto & Windus, 1898. “Mrs. Theresa Cornelys” by Edward Walford, M.A. Pp. 451-472. HERE

GoogleBooks. GROVE’S DICTIONARY OF MUSIC AND MUSICIANS. In Five Volumes. Vol. 1. J. A. Fuller Maitland, M.A., F.S.A., ed. “Cornelys, Theresa” by H. R. Tedder, Esq. P. 606. New York: The Macmillan Co., 1904. HERE

SusannaEllisAuthor.wordpress.com. “Romance of London: Mrs. Cornelys at Carlisle House” from ROMANCE OF LONDON: Strange Stories, Scenes and Remarkable Persons of the Great Town in 3 Volumes by John Timbs. Posted March 7, 2016. HERE

TheLancet.com. “Quacks and hacks: Georgian Medicine and the power of advertising” by Adrien Teal. Vol. 383, February 21, 2014. Pp. 404-405. HERE

Images:

Subscription ticket HERE By Sharp, William, 1749-1824 [engraver] Incledon, Charles Benjamin, 1763-1826 [performer]Carlisle House ([London], England) [author] [Public domain or CC BY 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Masque Ball ticket HERE By Sharp [engraver] Sharp [artist] Incledon, Charles Benjamin, 1763-1826 [performer]Carlisle House ([London], England) [author] [Public domain or CC BY 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Sources include:

Chancellor, E. Beresford. MEMORIALS OF ST. JAMES’S STREET and CHRONICLES OF ALMACK’S. New York: Brentano’s, 1922.

THE LONDON ENCYCLOPAEDIA 3rd Edition. Ben Weinreb, Christopher Hibbert, Julia Keay and John Keay, authors. London: Macmillan London Ltd., 2008.

GoogleBooks. Russell, Gillian. WOMEN, SOCIABILITY AND THEATRE IN GEORGIAN LONDON. “The Circe of Soho: Teresa Cornelys and Carlisle House.” Pp. 17-37. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007. (Preview) HERE

TheLancet.com. “Quacks and hacks: Georgian Medicine and the power of advertising” by Adrien Teal. Vol. 383, February 21, 2014. Pp. 404-405. HERE

Subscription ticket HERE By Sharp, William, 1749-1824 [engraver] Incledon, Charles Benjamin, 1763-1826 [performer]Carlisle House ([London], England) [author] [Public domain or CC BY 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Masque Ball ticket HERE By Sharp [engraver] Sharp [artist] Incledon, Charles Benjamin, 1763-1826 [performer]Carlisle House ([London], England) [author] [Public domain or CC BY 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

~~~~~~~~~~

About the author: Lauren Gilbert has been a member of the Jane Austen Society of North America since 2005. Her first published work, HEYERWOOD: A Novel, was released in 2011. Her second novel, A RATIONAL ATTACHMENT, is due out soon. She lives in Florida with her husband. Please visit her website HERE for more information.