The 12th century bishop, Henry of Blois, was the grandson of William the Conqueror. He attracted opprobrium from some contemporaries. Bernard of Clairvaux described him as ‘the man who walks behind Satan’ and ‘that old whore of Winchester’. For Henry of Huntingdon he was ‘a new kind of monster, composed part pure and part corrupt … part monk and part knight.’ Brian FitzCount accused him of ‘having a remarkable gift of discovering that duty pointed in the same direction as expediency’.

|

| Henry of Blois, British Library Public Domain Image |

Henry was probably the youngest of eleven children born to Count Etienne of Blois and Adela of Normandy, sister of King Henry I of England. As the youngest son Henry was superfluous to needs for the inheritance of his parents’ holdings and he was given to the monastery at Cluny as an infant.

Some elements of Henry’s history are well-documented and some may be apocryphal. Among the latter is that Henry went to Germany when he was around eleven with his eight-year-old cousin Matilda, daughter of King Henry of England, on her journey to marry Emperor Henry V. If this was Henry of Blois (rather than a different Henry), he was elected Bishop of Verdun in 1118 (aged around 20) on the recommendation of the emperor. The Pope arranged his consecration in Milan but, due to fierce controversy between the Pope and the emperor over who should appoint bishops, the emperor forbade the inhabitants of Verdun from receiving their bishop. Henry took refuge in the fortress of Hattonchatel. With military support, he was installed as bishop in 1120. If this story is true, we catch a glimpse of Henry’s willingness to switch allegiances to hang onto his power, which is repeated in later events in his life.

In 1120 the Anglo-Norman empire shuddered with the sinking of The White Ship in the English Channel. The ship was carrying the younger generation of Norman nobles including the 17 year-old heir to the English throne, Prince William Adelin. Henry of Blois’s sister Matilda, Countess of Gloucester, and her husband were also among the dead. Despite having at least twenty-four illegitimate children, King Henry was left without an heir and his new queen, Adelisa, appeared to be barren. The sinking of the ship led to a succession crisis in England.

In Germany, Verdun was stormed on the orders of Emperor Henry, the bishop was expelled, and escaped the emperor’s forces by swimming across the Meuse. If this story of Henry’s escapades is true it must have caused embarrassment to Empress Matilda since Henry arrived in Germany in her entourage and was then in defiance of her husband. The story has been questioned due to Henry’s age, however, there were other very young bishops who catapulted up the ranks through the power and wealth of their families. Furthermore, the incident seems in keeping with later events in Henry’s life when he took power and his loyalties twisted and turned as he clung onto the influence he had accrued and sought to expand it.

If Henry was in Verdun, it is possible that he was recalled to the Anglo-Norman empire in 1125 by King Henry, along with the Empress Matilda after the death of her husband. The king was contemplating his resources in the succession crisis and these included his widowed daughter and his nephews, Thibaut and Stephen of Blois, and their younger brother, Henry.

Once in England Henry rose rapidly in the Church, thanks to the patronage of his uncle. King Henry I was a youngest son who had climbed unexpectedly to power after the deaths and defeats of his older brothers and that may have been a source of inspiration to his nephew and namesake. In 1126 King Henry appointed Henry of Blois prior at Montecute in Somerset and then abbot of Glastonbury. Glastonbury was the richest and foremost monastery in England. On 1 January 1127 Henry of Blois was very likely among the English lords who swore an oath at Westminster Palace to uphold the rights of Empress Matilda as the king’s heir.

A few years later, in 1129, the king appointed his nephew bishop of Winchester, when Henry was probably around 30 years old. Very unusually and by special papal dispensation, Henry was allowed to retain his abbot’s mitre at Glastonbury at the same time as receiving the bishopric at Winchester. The combination of these two positions gave him an income that was 37% greater than that of the Archbishop of Canterbury.

|

| Historiated initial letter from the beginning of the Song of Songs from the Winchester Bible. Public Domain Image |

Henry was a generous patron of the arts. He commissioned the Winchester Bible and the Winchester Psalter and is depicted on the Henry of Blois plaque (image at end of article). Matthew of Paris described a magnificent sapphire pontifical ring that Henry gave to Saint Albans Cathedral. His extensive building works included renovations to Winchester Cathedral, Farnham Castle and Wolvesey Castle.

|

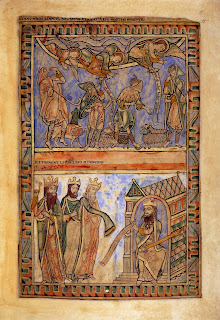

| The Annunciation to the Shepherds (top) and the Magi before Herod (bottom), Winchester Psalter British Library, Public Domain Image |

Many of the English lords were not happy at the idea of a woman on the throne, and they were even less happy with this solution to the succession crisis when the king married Matilda to Geoffrey, Count of Anjou. It is likely that Henry conspired with his brother Stephen and made plans for how they would act in the event of King Henry’s death. When King Henry died in Normandy in December 1135, Matilda was pregnant and unwell. She was unable to immediately claim the throne. The Anglo-Norman lords elected Thibaut of Blois as king of England, but his younger brother Stephen took swift action and usurped the throne from both Matilda and Thibaut. Stephen sailed from Boulogne in rough December seas. At Winchester the keys to the royal treasury were handed over by Bishop Roger, supported by Bishop Henry.

Henry of Blois attended the funeral of King Henry at Reading Abbey in early 1136, where he saw the hand of Saint James, which Matilda had brought back with her from Germany. Despite requests from the German court to return the relic, the empress had given it to her father, who had given it to Reading, his designated burial place. Henry of Blois ‘borrowed’ the hand of Saint James and took it back to Winchester where it doubtless attracted considerable revenue from avid pilgrims seeking cures. The reliquary was not returned to Reading Abbey until 1155, under the orders of Henry II.

With his brother as king of England, Henry could reasonably expect to rise further. When the archbishop’s throne in Canterbury became vacant in 1136 Henry coveted it. Orderic Vitalis claimed that Henry was elected archbishop. However, his expectations were thwarted since his candidacy was not supported by King Stephen and Henry did not receive papal confirmation. Stephen was probably pressured by other factions at court, including the queen and the twin earls of Beaumont and Worcester, who feared that Henry might exert too much influence on the king. Henry overcame this setback by getting himself appointed as papal legate to England in March 1139, which effectively gave him ascendancy over the Archbishop of Canterbury and the King.

Motivated, perhaps, by resentment, Henry called a church council in August 1139 to oppose Stephen’s dealings with Bishop Roger. Henry’s apparent championing of Roger on this occasion did not inhibit him from taking Roger’s role as Dean of St-Martin-Le-Grand, London and acquiring some of the disgraced bishop’s properties.

Henry of Blois had his fingers in the water at every turn of the tide during The Anarchy. The empress landed at Arundel in September 1139 with her half-brother Earl Robert of Gloucester ready to begin her long-awaited contestation for the throne. Stephen allowed her to leave Arundel and Bishop Henry escorted her towards Bristol. He may have written to his cousin urging her to come to England and claim her throne. In 1140 Henry went to France to discuss the civil war with King Louis VII and Thibaut of Blois and organised an inconclusive peace conference attended by Stephen’s queen, Matilda and Earl Robert of Gloucester.

After Stephen was captured by the empress’s forces at the battle of Lincoln in 1141, Henry switched sides. He met the empress near Wherwell and she agreed to make him her chancellor and defer to him on church matters. Henry received the empress at Winchester Cathedral as Lady of the English, the prelude to crowning her queen and ending the civil war. However, the accord between bishop and empress was short-lived. She flouted her agreement with Henry to defer to him by appointing William Cumin as bishop of Durham. When the empress’s highhanded actions in London caused another downturn in her fortunes, Henry had to flee the city with her. Henry argued with the empress over his nephew Eustace’s inheritance and they parted ways. She went to Oxford and Henry went to Winchester.

Henry next arranged a meeting with Stephen’s wife, Queen Matilda and switched sides again. The empress marched on Winchester and besieged Henry. He appealed to Queen Matilda for aid. The siege went on for six weeks, during which Henry’s forces burnt large parts of the city. The siege ended with a rout, the capture of Earl Robert and the escape of the empress.

When the prisoners, Robert of Gloucester and King Stephen were exchanged, Bishop Henry was obliged to patch things up with his brother. He called a council in London to declare Stephen the rightful king. In 1143, Pope Innocent II died and Henry lost his position as papal legate. He visited Rome in an effort to regain his position but was unsuccessful. In a further bid to secure ascendancy he proposed that Winchester be created a new archbishopric but was again unsuccessful. In 1149 Henry was King Stephen’s envoy in a mission to persuade King Louis of France to support Stephen against the advances of the empress’s son, Henry FitzEmpress, in Normandy. In 1154 King Stephen died and Henry FitzEmpress became Henry II, King of England.

William of Malmesbury, a friend and beneficiary of Henry of Blois’s patronage, described the bishop’s actions during the civil war in a favourable light, claiming that he was trying to do the best by the kingdom. Nevertheless, even allowing for the biases one way or another of the various commentators, a picture emerges of Henry of Blois as a man who might define the word tergiversator. He appears intent on wielding power by any means possible, hoping perhaps that first his brother King Stephen and then the Empress Matilda might be his puppets, or at least that he would have the foremost position in either court, depending on who emerged as the victor. Brian Fitzcount complained against Henry that ‘[my] main offence consisted in refusing to change sides as often as himself’.

|

| Henry of Blois plaque, showing kneeling, tonsured figure. Inscription reads: 'Art comes before gold and gems, the author before everything. Henry, alive in bronze, gives gifts to God. Henry, whose fame commends him to men, whose character commends him to the heavens, a man equal in mind to the Muses and in eloquence higher than Marcus [that is, Cicero]' Image Credit |

Bishop Henry assisted at the coronation of Henry II as king of England, but perhaps trepidatious about how the new king might view his equivocations and his wealth, he left England without the king’s permission and retired to Cluny for a few years, sending his treasure on before him. King Henry promptly ordered the destruction of Bishop Henry’s castles. After his cautious return to England, Henry of Blois had a part to play in one more significant episode in English history. He was amongst the bishops forced to sign the Constitutions of Clarendon by King Henry II against Thomas of Becket and presided over Thomas’s trial at the same time as secretly supporting the archbishop’s family.

Another of the possibly apocryphal stories associated with Henry is Francis Lot’s controversial theory that Henry was the author of the Gesta Stephani (an account of the life of King Stephen) and that Geoffrey of Monmouth, the author of The History of the Kings of Britain, was his nom de plume.

Bishop Henry died in his seventies in 1171. King Henry II visited him as he lay dying. When Henry’s body was discovered in 1761 in a sepulchre in Winchester Cathedral it was ‘wrapt in a brown and gold mantle, with traces of gold round the temples’. Henry of Blois emerges from the traces of history as a man who lived sumptuously and who was impressively presumptuous.

~~~~~~~~~~

Tracey Warr’s novels are set in early medieval Europe. Almodis was shortlisted for the Impress Prize and the Rome Film Festival Book Initiative. It is based on the life of Almodis de La Marche, who was described by William of Malmesbury as being ‘afflicted with a Godless female itch’. The Viking Hostage recounts the true story of a French noblewoman kidnapped by Vikings. Warr’s trilogy Conquest follows the tumultuous life of the medieval Welsh princess, Nest ferch Rhys. It was supported by a Literature Wales Writer’s Bursary. Warr’s next project, Three Female Lords, has received an Author’s Foundation Award and is a biography of three sisters who lived in 11th century southern France and Catalonia. She is Head of Research at The Dartington Trust and teaches on MA Poetics of Imagination at Dartington Arts School. Her latest novel Conquest III: The Anarchy is published by Impress Books on 2 June.

Purchase link: Amazon

social media links:

Twitter - @TraceyWarr1

website links:

TraceyWarrWriting

http://www.impress-books.co.uk

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.