By Kim Rendfeld

A woman who was once a murderous queen of the West Saxons winds up begging in the streets of Lombardy. Lovely poetic justice, if only it were true.Eadburh, daughter of Mercian King Offa and Queen Cynethryth, was a real person. She did marry a king and was widowed. And she might have ended her days in Lombardy, but not begging and for much more mundane reasons than those in a story written by an author currying favor with a political enemy.

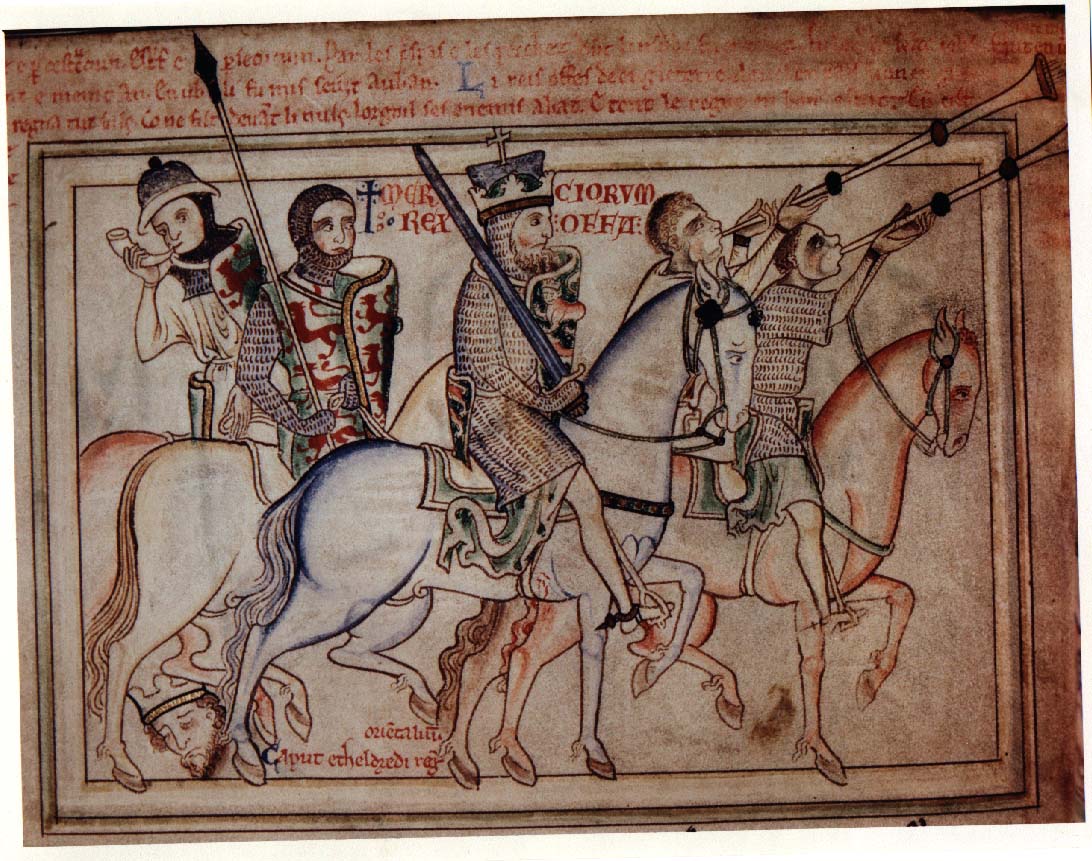

Offa (d. 796) was known for his ruthlessness and for the dike bearing his name. Like most aristocrats, he and his wife arranged for their children to marry for political advantage. In 789, Eadburh wed Beorhtric, king of Wessex.

|

| Offa of Mercia from Matthew Paris's tract on St. Alban, 13th century (Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons) |

Apparently, Eadburh did wield power and influence. She gave away land in her own name and witnessed charters with her husband and her brother. Even though her marriage to Beorhtric lasted several years, they didn’t have children. Men in this age sometimes tried to repudiate wives who didn’t produce a healthy son. Beorhtric seems to have been a steadfast husband. Or maybe he feared upsetting Eadburh’s parents more than dying without an heir.

After Offa died, his son, Ecgfrith, succeeded him, and Beorhtric and Eadburh supported him. But Ecgfrith’s reign didn’t last even a year. He died, likely not of natural causes.

Eadburh and Beorhtric’s marriage lasted until his death in 802. He didn’t die of old age, either.

|

| 13th century image of Beorhtric (Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons) |

And now we get to the fiction, an account by Asser, who wrote Life of Alfred in 893. The title character was Ecgberht’s grandson. Asser supposedly includes Eadburh’s story to explain why the wives of the Wessex kings weren’t crowned queen like Eadburh was and not take her seat beside him on the throne. More likely this is an attempt to discredit the rival family.

If we are to believe Asser—and I don’t—Eadburh was tyrannical like her father and dominated the relationship (not good in medieval eyes). If her husband liked anyone she didn’t, she would poison the friendship, and if that didn’t work, the poisoning took a literal turn. Poison, the weapon of women and cowards, fits nicely into the narrative.

Eadburh planned to kill a young man she thought was getting too close to her husband. The victim took the poison. So did Beorhtric. Oops.

In reality, Ecgberht is the more probable culprit. He might have invaded Wessex with his followers, and Beorhtric fell in battle. Ecgberht subsequently seized the throne.

According to Asser, Eadburh took treasures and fled. That much is believable. What’s next is a stretch, and that’s being charitable.

Eadburh went to Charlemagne’s court. The emperor, whose fifth wife had died, asked Eadburh if she wanted himself or his son Charles. Eadburh said she preferred the younger man. Charlemagne told her had she chosen the father, she would have gotten the son, but now she could have neither.

This doesn’t pass the laugh test. By medieval standards, Eadburh was not a desirable bride, especially for a royal marriage. Her father and brother were dead, leaving her without the family connections needed to form alliances. Instead, Charlemagne appointed her as an abbess.

|

| Charlemagne by Albrecht Dürer (public domain, via Wikimedia Commons) |

She might have spent the rest of her days in Lombardy but not as a punishment or in poverty. A confraternity book written between 825 and 850 shows an “Eadburg” as an abbess of a large Lombard convent. If this Eadburg is the former queen of Wessex, she would be in her 50s to her 70s.

It was common for a widowed queen to retire to a convent, and if the emperor thought her a reliable ally, he might appoint her as the abbess. An abbess was a leader, controlling land and the convent’s other assets, and she usually did not live an ascetic lifestyle.

The real Charlemagne very much believed in the power of prayer, and that extended to winning wars. If he trusted Eadburh to lead her sisters in prayer, it is possible he or his successor, Louis the Pious, might have bestowed the abbey upon her.

Sources

"Eadburh" by Janet L. Nelson, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

“Beorhtric” by Heather Edwards, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Asser’s Life of Alfred

Asser's Life of King Alfred, together with the Annals of Saint Neots erroneously ascribed to Asser

by John Asser, d. 909, edited by William Henry Stevenson

“A handsome, but wretched head.” by Lisa Graves, The History Witch

“Eadburh, Queen of the West Saxons” by Susan Abernethy, The Freelance History Writer

~~~~~~~~~~

In The Cross and the Dragon, a Frankish noblewoman must contend with a jilted suitor and the fear of losing her husband (available on Amazon). In The Ashes of Heaven's Pillar, a Saxon peasant will fight for her children after losing everything else (available on Amazon). Her short story “Betrothed to the Red Dragon,” about Guinevere’s decision to marry Arthur, is set in early medieval Britain and available on Amazon.

Connect with Kim at on her website kimrendfeld.com, her blog, Outtakes of a Historical Novelist at kimrendfeld.wordpress.com, on Facebook at facebook.com/authorkimrendfeld, or follow her on Twitter at @kimrendfeld.

Interesting post! Knowing an era's general history , such as the role of an abbess, is vital in such detective work!

ReplyDelete