To Wear or not to wear a wimple

|

| Boudicca Public Domain |

|

| Photo Originally uploaded by Deacon of Pndapetzim CC BY-SA 2.5 |

If we look back through history, the earliest documentation of the code seems to have first been promoted by St Paul. Paul, who was both a Jew and a Roman citizen, is thought to be the first apostle who spread the teachings of Christ throughout Asia Minor and Europe. He preached that women should cover their hair as submission to their husbands and when praying in church. In a letter to Timothy, he stated that women should dress modestly and not with 'broided' (meaning twined, braided) hair, or gold, or pearls, or costly array. But Paul was not the only one who lectured women on their modesty. Tertullian, a theologian writing in 200 AD, wrote that St Paul was not just referring to married women, but 'all women of age', most likely meaning those who had reached puberty. He admonishes those women who do not cover the whole of their head, leaving their ears and neck exposed. It seems that in covering the whole of one’s head, women were avoiding being gazed at, and were also encouraged to be ‘entirely’ covered, unless they were at home. Thus, it was the responsibility of women to ensure that they did not fall prey to sin, or to the lust of men, not the other way around, as according to the writings of Clement of Alexandria.

|

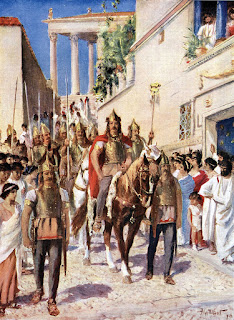

| Alaric enters Rome [Public Domain] |

When the exact date was of the arrival of Christianity in Britain, is not known, however, it is apparent both in archaeological and textual sourced that it was well established by the 5thc. Literature suggests that Roman women were required to cover their hair in public when walking out, but the evidence of images at this time in Britain suggests otherwise. Perhaps if the doctrine of hair-covering for modesty had reached these shores, it was not fully enforced.

The Pictish Hilton of Cadbol stone, in the picture above, which dates to around 800AD, has a Christian cross on one side of it, and a secular riding scene on the other, with a high-status lady riding side saddle, her hair uncovered. This is a reconstruction of the stone to show you clearer detail of what she is wearing and how her hair looks. It is not known who she is, but on her right are a mirror and a comb, indicative of her gender. It looks very much like a hunting scene, and the fact that she is riding side-on is intriguing, but the main delight is the way her hair is depicted in cascading waves down her back. It is fascinating, that even as late as this time, the Christian doctrine of wearing veils for modesty was not necessarily in play this far north, though it could be artistic licence. And it does not mean that the rule for church did not apply when it came to prayer time.

Reenactor, Rhydian Jones states, “If you’re on the east coast north of the Forth prior to 850 AD (ish) and doing Pictish (reenactment), the majority of evidence is that women wore their hair uncovered, and frequently wore a large cloak/shawl fastened in the centre of the chest with a penannular brooch… The bigger the brooch the posher you are.” The lady on the stone does seem to have a very large brooch. This cloak could have been pulled up over her head to provide extra warmth in inclement weather. Also, seperate hoods have been indicated also.

|

| A cap showing the Sprang technique used by Germanic women Photo by Lyllyundfreya CC By-SA 30 |

In looking at the evidence for headdress in early the middle ages, in what was later to become England, it seems that the evidence, both archaeological and documented are scarce and what evidence there might be is debatable. That’s not to say that veils weren’t worn, just that there is a paucity of evidence. As I have said earlier, I believe that women wore head-coverings of some sort even in pagan times for the reasons I had previously mentioned, and not just for modesty. Among the dubious evidence found are small rings that might have been used for braid fasteners, but generally the consensus is that these are not practical for such a purpose. Gold brocaded fillets have also been found, but it is not known if they were worn to secure a veil, or worn without the veil.

To find evidence of what women in the British Isles might have worn on their heads, we need to look to their counterparts abroad: It is known that Germanic women in ancient Scandinavia wore caps, samples from bronze and iron age have been found to be woven in sprang, an ancient technique used in Denmark and other parts of the ancient world that made them look like hairnets. An example was found on the body of a girl recovered from the Arden Mose wearing hers over 2 coiled plaits of hair.

|

| The Arden girl's hair [Public Domain] via Wikimedia Commons |

There is no evidence of sprang technique being used by Anglo-Saxon women though the technique was known in Britain. Drawstring-style caps were found to be worn on the figures of women wearing a Menimane Rhineland costume dated from the 5th/6th centuries. It is likely that these types of caps might have been worn in Anglo-Ssxon areas at this time.

Women in Iron Age Denmark regularly wore scarves. A bog body was found wearing a scarf at Huldremose, 1.37 metres long and 49 cm wide with fringed ends. Anglo-Saxon women may have worn similar types of veils/scarves and tabby-woven material has been found on the backs of brooches. The Merovingian queen, Arnegundis, was found in her tomb with a long red satin veil, secured by two small pins at her temples. This long veil was quite common in this period. Arnegundis seems to have favoured a longer, elaborate veil that might have been crossed over the breast and pinned, and hung over an arm. A parallel for this veil was found in the grave of the woman at Mill Hill, in Deal, Kent. Two clips have also been found like the Merovingian woman at the sides of a woman’s head in Cambridgeshire, showing that the fashion might have travelled to south-eastern parts of England. To view an reconstruction of Arnegundis' burial outfit, check this link

There is a considerable amount of linguistic evidence for head gear in Anglo-Saxon:

Haet, - AS for hat.

Cuffie - a loose fitting hood.

Scyfel - a hat or a cap with a projection.

Binde – a fillet. Binde may have been the name for the gold-brocaded fillet that a very few 6thc c women wore. Cloth ones would have left no trace.

Snod – Snood in AS in Old Norse - hofuthbond

So, in summarising, where the western world is concerned, it seems the nearer to Rome and the Orthodox Christian region, the more likely that head-covering was worn, mostly in respect of church teachings. We have seen that there is less evidence for wearing head-coverings than there is for not, and less archaeological evidence than documented or art. But we cannot discount the wearing of headwear for practical reasons, such as for work or for hygiene as opposed to following a religious moral code, but this does not increase the lack of finds.

The next post in the Wimples, Veils, and Head-rails, we venture down our time tunnel to focus on the centuries between the late 7th – 9th centuries. Please join me in this fascinating adventure to find out what we can about women in this time of so-called darkness, and shine a light on their lives.

References

Tertullian, The Veiling of the Virgins, The Ante-Nicene Fathers Vol.4 pp27-29,33.

Clement of Alexandria.

Rhydian Jones

Further reading

http://www.vikingage.org/wiki/wiki/Main_Page

Owen-Crocker G.R. 2004 Dress In Anglo-Saxon England The Boydell Press, UK.

~~~~~~~~~~

Paula Lofting is an author and a member of the re-enactment society Regia Anglorum, where she regularly takes part in the Battle of Hastings. Her first novel, Sons of the Wolf, is set in eleventh-century England and tells the story of Wulfhere, a man torn between family and duty. The sequel, The Wolf Banner is available now. Paula is currently working on the third book in the series, Wolf's Bane

Find Paula on her Blog

on her Amazon Author Page

Very interesting post, thank you for writing and sharing it.

ReplyDeleteThank you for your comment Lynne

Delete