by Paula Lofting

In this final examination of this mystery, I do not aim to prove,what the image of Alfgyva and the priest represents. It would be impossible, because there is no evidence to draw on – at all – that is irrefutably connected to the scene. Mind you, if there was, I’m sure it would have been discovered years ago. So, my mission is to explain, and perhaps persuade, my theory of who she is and what the scene could be portraying. We will never know the full truth behind the image and what the artist was trying to convey, the real message has been lost down the tunnel of time and has died with those who have long since lived those events.

I imagine that in the same way one might glance at the front page of a modern newspaper, read the first line of a headline story and know exactly what the author was referring to, so the contemporaries of the Tapestry would also know about the well-known scandal of the time. The people of the 11thc may not have needed any more explanation than the image of Alfgyva and the priest for them to know who the artist was referring to – or – it might be that there was some secret underlying message linked to the woman and the priest contained within the borders of the tapestry that reports something else only known to certain people. No one can be sure. One could also say (and some have), that the images in the borders could be there for decorative purposes only, and have nothing whatsoever to do with the message the Tapestry is trying to send.

So to summarise, we discovered earlier on who the lady in question is and to my mind this is as indisputable as it can get. She was Ælfgifu of Northampton, handfastened wife of King Cnut, and it was J Bard McNulty (1980) who first identified her. She was sent by Cnut to Norway to govern there with their eldest son Swein, however her heavy handed rule did not endear her to the Norwegians and they eventually ousted her and her son. Poor Swein died in Denmark where they had both sought refuge. Nothing was heard about her after 1040, but she had become the subject of a scandal years before, when she was accused of presenting Cnut with two sons that were actually neither hers nor his. One was rumoured to be the son of a priest and a serving maid and the other was the son of a workman and perhaps herself or the same servant maid.

Regarding her connection to the Bayeux Tapestry, what could she possibly have had to do with the story of Harold’s sojourn in Normandy? As I explained previously in Part V, J.McNulty Bard (1980) states in The Lady Ælfgyva in the Bayeux Tapestry that the scene depicting Ælfgyva and the priest is not what happens next in the story, but what Harold and William are discussing in the previous scene. This is highly possible, for it is the only scene that doesn’t follow the previous one. But with the absence of speech bubbles, it is still pretty much conjecture, though I can say with confidence that of all the theories, this one has substance to it.

In this final examination of this mystery, I do not aim to prove,what the image of Alfgyva and the priest represents. It would be impossible, because there is no evidence to draw on – at all – that is irrefutably connected to the scene. Mind you, if there was, I’m sure it would have been discovered years ago. So, my mission is to explain, and perhaps persuade, my theory of who she is and what the scene could be portraying. We will never know the full truth behind the image and what the artist was trying to convey, the real message has been lost down the tunnel of time and has died with those who have long since lived those events.

I imagine that in the same way one might glance at the front page of a modern newspaper, read the first line of a headline story and know exactly what the author was referring to, so the contemporaries of the Tapestry would also know about the well-known scandal of the time. The people of the 11thc may not have needed any more explanation than the image of Alfgyva and the priest for them to know who the artist was referring to – or – it might be that there was some secret underlying message linked to the woman and the priest contained within the borders of the tapestry that reports something else only known to certain people. No one can be sure. One could also say (and some have), that the images in the borders could be there for decorative purposes only, and have nothing whatsoever to do with the message the Tapestry is trying to send.

So to summarise, we discovered earlier on who the lady in question is and to my mind this is as indisputable as it can get. She was Ælfgifu of Northampton, handfastened wife of King Cnut, and it was J Bard McNulty (1980) who first identified her. She was sent by Cnut to Norway to govern there with their eldest son Swein, however her heavy handed rule did not endear her to the Norwegians and they eventually ousted her and her son. Poor Swein died in Denmark where they had both sought refuge. Nothing was heard about her after 1040, but she had become the subject of a scandal years before, when she was accused of presenting Cnut with two sons that were actually neither hers nor his. One was rumoured to be the son of a priest and a serving maid and the other was the son of a workman and perhaps herself or the same servant maid.

|

| William secures the release of Harold from the Count of Ponthieu and brings him to his palace where they discuss the woman in the next scene. |

|

| William returning with Harold to his palace in Normandy |

In order to reach the point where we can deliberate the conversation between Harold and William, we need to discuss the scene with the two men in detail. This is the one before the Aelfgyva scene. William and Harold have just arrived at William’s court from having ridden from Ponthieu where Harold had been kept, probably for ransom, by the young Count after washing up on his shore with his personal guard. According to Eadmer, somehow, a huscarle of Harold’s, escaped and called upon William for his help in releasing his lord from the clutches of Count Guy. William was the count’s overlord and demanded that Guy hand Harold over immediately, which he did.

Now, we move on, William sits on his throne in his hall with a Norman guard standing behind him with a spear. This man appears to be pointing at Harold. The viewer can differentiate between the Normans and the English by their hairstyles. There is little disparity with the English and Norman clothing of the day, but their hair styles are very different with most Normans wearing their hair short and shaved at the back to just above the ears. The artist has obviously marked these out to give a clear distinction between the two races. The image of Harold is shown with his hair covering his ears and just above collar length. Curiously, the guard standing directly behind him as he converses with William, is not shown as a Norman.

This man is also sporting an English style hair cut and a beard. The Normans are generally shown as being clean shaven. The English either have beards or moustaches. As we can see, the rest of William’s household guards are looking very Norman-like in contrast to the one that Harold appears to be indicating to.

As stated by Eadmer in his History of Recent Events in England, Harold had travelled to Normandy with the intention of negotiating the release of his brother Wulfnoth and his nephew Hakon. These two particular Godwinsons had been taken into Edward’s care as hostages to ensure the good behaviour of their patriarch, Godwin, in 1051, when had Godwin found himself in trouble with Edward. His refusal to punish the people of Dover for their ‘maltreatment’ of the king’s brother-in-law, Count Eustace of Bologne and his retinue, had been the cause of this discontent between the earl and his king (Barlow 2002).

Godwin had rallied his supporters to side with him against the king. At that time, the great nobles of the day were reluctant to support a civil war and so Godwin had no choice but flee into exile, leaving his son Wulfnoth and grandson Hakon behind as hostages. It is not exactly clear how Wulfnoth and Hakon, both young boys at the time, came to find themselves in Normandy, but it was quite possible that the Archbishop, Robert Champart took them with him when Godwin forced his way back to England from exile a year later. Champart had helped to engineer Godwin’s fall from grace and so feared for his life and fled back to Normandy.

It is believed that he used the boys to shield him from those who would stop him leaving the country and brought the boys with him to present to William as surety for Edward’s promise of the crown. This might have been with Edward’s agreement, but must have been a decision that Edward later wished to forget, for he was eventually to sanction a mission by Bishop Ealdred to go abroad to look for Edward’s nephew, known as Edward the Exile, son of his brother, Edmund Ironside.

So, Eadmer, a monk and chronicler of Canterbury, has in his writings, Harold travelling to Normandy on a mission to secure the release of his kin with a stark warning from Edward that this may not be a good idea and that he will be inviting trouble for himself and ‘the whole kingdom’ if he does indeed embark on this journey. Edward warns Harold that the duke is ‘not so simple’ as to give the hostages up without getting something in return. Edward apparently also states, as Eadmer tells us, that he wanted no part in Harold’s plan.

And yet Harold still went, frivolously, one might think, considering Edward’s warning about the nature of his second cousin. This story reveals that not only was Harold possessed of a stubborn nature, it also shows that the king’s power over his subordinate was weak, for he was unable exert his kingly influence over him and persuade him not to go. But whatever Harold’s determination to ignore his king’s advice, he must have been disturbed by the plight of his brother and nephew, languishing in Normandy long after the need for them to be hostages. The original purpose for their detention had been to ensure Godwin’s good behaviour and the patriarch of the family had long been dead. Harold, I am sure, wanted only to bring them home.

The Norman sources tell a totally different tale. They insist that Harold had been sent by Edward to confirm the succession upon him (Harriet Harvey Wood 2008). I prefer Eadmer’s version, for it holds more weight. He was said to have had access to people who might have had first hand information about Harold’s intentions when he went to Normandy. It is a plausible suggestion and upon studying the images of the Tapestry, I have not seen anything that might not support this idea; having said that, the Tapestry does support both the Norman and Eadmer’s version.

So now, what are my conclusions? Well, you will have to wait until tomorrow to hear the rest of the story in the final concluding episode of this long, twisted journey back to the past.

~~~~~~~~~~

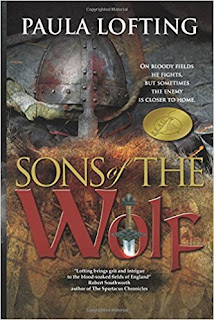

Paula Lofting is an author and a member of the re-enactment society Regia Anglorum, where she regularly takes part in the Battle of Hastings. Her first novel, Sons of the Wolf, is set in eleventh-century England and tells the story of Wulfhere, a man torn between family and duty. The sequel, The Wolf Banner is available now. Paula is currently working on the third book in the series, Wolf's Bane

Find Paula on her Blog - The Road to Hastings & Other Stories

on her Amazon Author Page

Read the rest of this blog series:

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.