|

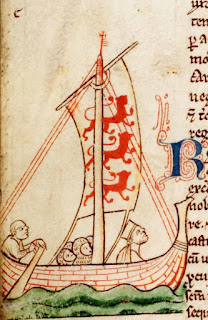

| Henry on his way to France |

After some consideration, Henry decided that the woman best placed to become his wife was a certain Jeanne de Dammartin. The lady came with various benefits, the principal one being that she stood to inherit not only the county of Ponthieu but also Aumale, thereby giving Henry III a foothold in Normandy and an opportunity to recoup on everything his father, King John had lost.

Further to this, Jeanne also came with an impressive pedigree, being the granddaughter of the princess Alys, that unfortunate woman who was promised to Richard Lionheart as his wife, raised in England where she purportedly was seduced by her future father-in-law, Henry II, returned as soiled goods to France where her brother, King Philippe Augustus, hastily married her off to the much, much younger William of Ponthieu. Not that Henry III cared all that much about Alys’ unhappy life: the important thing was that little Jeanne had Capet blood in her veins.

|

| Jeanne's uncle on his way to his prison |

Renaud’s brother (Jeanne’s father), Simon, had fought with his brother at Bouvines. After the battle, he fled and spent a number of years in exile. His wife, Marie of Ponthieu, was left holding the can, so to say. Philippe Augustus had had it with the Dammartins, and when Simon’s father-in-law passed away, he therefore denied Marie her inheritance, which seems rather unfair as Marie’s father had fought for Philippe Augustus.

Fortunately for Marie (and, indirectly, for Jeanne) Philippe died in 1223. His son proved easier to negotiate with, so Marie was recognised as countess of Ponthieu and after a further few years of negotiation, Simon was allowed to come back home. To show his goodwill, Simon made a promise that he would not marry off any of his daughters without the consent of the French king. As an aside, it is interesting to note that his daughters were all born in the 1220s when Simon officially was exiled. I’m guessing that old adage “distance makes the heart grow fonder” was valid for Simon and his Marie as well, ergo a certain willingness to take risks to meet and hold each other.

By the time Henry III decided to pay court to Jeanne, twenty years had passed since the Battle of Bouvines. So maybe Henry was hoping that bygones were bygones – or maybe he didn’t know that the Dammartin daughters could not be wed without royal French consent. Whatever the case, negotiations started in secret in 1234. Simon and Marie were likely delighted at the idea that their eldest would become queen consort of England, their grandson a future king.

|

| Queen Blanche |

|

| Eleanor of Provence |

Queen Blanche was Castilian by birth, daughter of Alfonso VIII and Eleanor of England. Eleanor was Henry III’s aunt, so Blanche and Henry were cousins, albeit Henry was close to two decades younger than Blanche and thereby of an age with Blanche’s precious son, Louis. He was also of an age with King Fernando of Castile, Blanche’s nephew. (It all gets a bit complicated here: Fernando and Louis were first cousins, Henry was first cousins with both Blanche and Berenguela, Fernando’s mother)

In 1235, Fernando’s first wife, Elizabeth of Hohenstaufen, known as Beatriz in Spain, died. By all accounts, Fernando and Beatriz had enjoyed a happy—and fruitful—marriage. Now, the Castilian kings had a bit of a reputation when it came to women, but as long as Fernando had been married to Beatriz, he’d shown little inclination to stray. This may have been because Fernando spent most of his life fighting the Moors, women and leisure being something he rarely had time for. His mother Berenguela decided it was better to be safe than sorry and started looking for a new wife for her son. Blanche was quick to suggest Jeanne and Berenguela approved.

|

| Fernando |

Whether she objected or not, in 1237 Jeanne and Fernando were wed in Burgos. In 1239 she gave birth to a son, Fernando, who would go on to become Count of Aumale. Some years later, she gave birth to a daughter, Leonor. Three more sons followed of which two died very young.

In 1252, Jeanne became a widow, her dying husband entreating his eldest son and heir to treat his stepmother fairly and with kindness. Not much of that around, as Alfonso never warmed to Jeanne whom he found severely lacking compared to his own saintly mother. Even worse, Jeanne conspired with Alfonso’s younger brother Enrique when this disgruntled gent threatened rebellion. There were even rumours that Jeanne and Enrique were lovers, but that should probably be treated as salacious gossip.

Upon his deathbed, Fernando also commended the care of his younger children to his eldest son, and while Alfonso may have had issues with his stepmother, he seems to have genuinely cared for his half-siblings. Especially for Leonor.

While Jeanne had been in Spain birthing babies, Henry and his Eleanor had been in England doing the same. Well, not Henry, obviously, but he was more than delighted when his eldest son, Edward, was born in 1239, interestingly enough at almost the same time as Jeanne’s first boy was born. Some years down the line and Henry started looking for a bride for his son. As always, a royal marriage was a negotiating tool, and in this case Henry wanted to come to some sort of accord with Alfonso X of Spain, this related to a dispute involving Gascony going back to the wedding between Eleanor of England and Alfonso VIII.

|

| Alfonso |

Late in 1254, Leonor married the recently knighted Prince Edward. They would go on to have a long and happy marriage, albeit marred by all those babies who died. Something of a full circle, one could say, the son of Henry marrying the daughter of Jeanne.

While Leonor—oops, Eleanor—adapted to her new life, Jeanne was enjoying the relative freedom of being a widow with a steady income. As Countess of Ponthieu in her own right she had the wherewithal with which to spoil herself and others. Truth be told, Jeanne had quite the indulgent side to her, so she happily spent far more than her income. Soon enough, the title passed to her son, but this did not stop Jeanne’s lavish spending and I am guessing her son was more than relieved when dear mama married again. Jeanne’s eldest son died in 1265, the title of Count of Aumale passing to his young son. The title of Count of Ponthieu passed to Jeanne’s second surviving son, Louis, but he too was destined to die relatively young and due to the customs of Ponthieu, his children could not inherit the title. Instead it reverted to Jeanne.

Upon Jeanne’s death in 1279, Ponthieu—and Jeanne’s huge debts—passed to Eleanor (and Edward). That piece of land which the French had been so determined to keep from the English king now became an English fief and would remain so until 1369. I wonder what Queen Blanche would have thought of that!

All pictures in public domain and/or licensed under Wikimedia Creative Commons

~~~~~~~~~~~

Had Anna Belfrage been allowed to choose, she’d have become a professional time-traveller. As such a profession does not exist, she became a financial professional with two absorbing interests, namely history and writing.

Presently, Anna is hard at work with The King’s Greatest Enemy, a series set in the 1320s featuring Adam de Guirande, his wife Kit, and their adventures and misfortunes in connection with Roger Mortimer’s rise to power. And yes, Edmund of Woodstock appears quite frequently. The first book, In The Shadow of the Storm was published in 2015, the second, Days of Sun and Glory, was published in July 2016, and the third, Under the Approaching Dark, was published in April 2017.

When Anna is not stuck in the 14th century, she's probably visiting in the 17th century, specifically with Alex(andra) and Matthew Graham, the protagonists of the acclaimed The Graham Saga. This is the story of two people who should never have met – not when she was born three centuries after him. The ninth book, There is Always a Tomorrow, was published in November 2017.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.