by Cryssa Bazos

Late one Sunday night on November 9, 1651, a company of dragoons descended upon a barber’s house on Fleet Street to arrest one of his lodgers. The soldiers burst into the man’s quarters, pistols drawn, and hauled him to the Speaker of the House of Commons, William Lenthall. The next day, they brought their prisoner to Whitehall to be questioned.

The state had finally captured Captain James Hind, notorious highwayman, but their interest in him went beyond common thievery. He had become a political figure.

James Hind was born in the Oxfordshire town of Chipping Norton in July of 1616, the tenth of thirteen children. His father was a respectable saddler and served as a churchwarden. Hind married Margaret Rowland on February 24, 1638, and their affectionate marriage produced four children: Alice, James, Samuel and Charles. But Hind’s domesticity masked a nearly twenty year run as a highwayman.

The seeds of Hind’s nefarious career had started in the local grammar school. His father had recognized his son’s sharp mind and diverted a portion of his income to educate the boy. Unfortunately, Hind preferred the study of pranks to letters, and he loved tales of high adventure, particularly crime stories. By the age of fifteen, Hind had outstayed his welcome in school. His father apprenticed the lad to a butcher, but subservience did not suit Hind. Fed up by the beatings he received for his impertinence, he ran away to London.

Imagine the world of corruption that suddenly opened up for this clever Chipping Norton lad: drinking, carousing, and visiting houses of ill repute (he hadn’t married to Margaret yet). His life took on a new direction, or rather an inevitable one, when he met Thomas Allen in a holding cell following a drunken spree. Allen, also known as Bishop Allen, led a gang of highwayman working the London suburbs. Allen took the young Hind under his wing and introduced him to life on the highway.

During his coming-out robbery at Shooter’s Hill, Hind held up a gentleman and stole £10. To the dismay of his new crew, he returned part of the booty, a sum of forty shillings, to see the gentleman safely back to London.

Hind’s wit and generosity became his calling card and he developed a reputation as a gentleman robber, often jesting with his “clients” and giving good sport. Not surprising many of his exploits had a Robin Hood feel to them. Once, when travelling through Warwickshire, Hind came upon two bailiffs and a usurer who were trying to collect from an innkeeper a debt of £20. Hind intervened to save the landlord and settled the bond on his behalf. After the bailiffs received their due, Hind ambushed the usurer and stole back not only his £20 but also another twenty for good measure. When he returned to the inn, he gave the innkeeper £5 and said that he “had good luck by lending to honest men.”

Then in 1642, the English Civil War broke out, and Hind turned his talents for the benefit of the King. Together with other members of the Bishop Allen gang, he joined the Royalist army. Hind’s leadership and courage drew the attention of his superiors, and he became particularly attached to Sir William Compton, third son of the Earl of Northampton of Warwickshire. In 1647, Hind received his captain’s commission from Compton at Colchester. In later years, Compton would found the Sealed Knot, a secret society that conspired to place Charles Stuart (later Charles II) on the throne.

Following the end of the second civil war (1647-48), Hind began to operate alone, for sometime in 1648, Allen and most of his crew were captured after a foiled attempt to assassinate Oliver Cromwell. Hind had managed to escape and returned to highway robbery with a new purpose: harassing Roundheads, and his preferred quarry were regicides when he could get them.

According to legend, Hind held up the man who presided over the King’s trial, a regicide by the name of John Bradshaw. Hind caught the judge on the road in Dorsetshire. When Bradshaw tried to intimidate the highwayman with his reputation, Hind retorted, “I have now as much power over you as you lately had over the King, and I should do God and my country good service if I made the same use of it.”

Hind had become more than a highwayman; he was now a symbol of resistance for the Royalists and a burr in the saddle of Parliament. But he didn’t stop there. At one point, he must have realized that he could contribute more to the Crown than stealing from Roundheads.

On May 2, 1649, Hind sailed for The Hague and stayed there for three days before continuing to Ireland laden with the “King’s goods”, supplies destined for the Royalists' resistance against Cromwell. Not surprising, the Earl of Northampton, William Compton’s eldest brother, spent his exile in The Hague.

Hind remained in Ireland for nine months and served as corporal in the Marquess of Ormonde’s Life Guard. He eventually arrived in Scotland and presented himself to Charles Stuart. In Hind’s declaration, he “sent a letter to His Majesty acquainting His Highness of my arrival, and represented my service, &c, which was favourably accepted of, for no sooner had the King notice of my coming but immediately I had admittance to his chamber and kissed his hand.”

While Charles may have been desperate for men, this special treatment stands out as unusual. Were the King’s actions a result of his relief over receiving the services of a courageous, resourceful soldier or had Hind arrived with a recommendation? Though naturally audacious, that he dared send a letter to the King suggests he expected to be received.

Hind joined the King’s army and stayed with him through the invasion of England in August 1652, which ended with defeat at the Battle of Worcester on September 3, 1652. At the battle, Hind “kept the field until the King was fled” then headed for the anonymity of London, lying under hedges and in woods. When he arrived in London, rumours were already circulating that the infamous highwayman, Captain Hind, had helped the King escape Worcester. He managed to elude capture for five weeks, but eventually the dragoons found and arrested him.

Over the next several months, Hind went through three sensational trials. The bizarre twists would have today earned him round the clock media coverage.

His first trial occurred on Dec 12, 1651 at the Old Bailey. Hind admitted to a few ‘pranks’ and even confessed to fighting with the King at Worcester. Though they could have charged him with High Treason, no Bill of Indictment or witnesses were brought against him. But he remained in close custody at Newgate.

Hind’s second trial was held in Reading on March 1, 1652. The state charged him with the murder of a local man who had once tried to stop Hind in Maidenhead Thicket. In fact, this was the only reported murder attributed to him throughout his long career as a highwayman. Hind stated that he fired on the man in self-defence.

At this point, Hind claimed benefit of clergy, a legal loophole that dated back to 1170 when the clergy were considered outside the jurisdiction of secular courts. To succeed, the defendant would need to read the scripture given to him (because in the 12th century, few except the clergy could read). Unfortunately, Hind failed the test, and they sentenced him to death. He must have regretted not applying himself better in school.

But reprieve came from the most unlikely source. The next day, before the sentence could be carried out, the Act of Oblivion came into force. The Act allowed for many crimes committed prior to September 3, 1651 (the Battle of Worcester) to be pardoned as an act of war, all except High Treason.

Now Parliament became desperate. Chapbooks and broadsheets tallying Hind’s exploits flooded London. One local publisher even released The Declaration of James Hind, an official account of his service to the King. All this publicity made Parliament look bad.

The gloves came off. The state turned to the Act of Oblivion for their cue and indicted Hind with High Treason for his participation at Worcester. For Parliament, the third trial was the charm. The court found Hind guilty and sentenced him to be hanged, drawn and quartered.

On September 24, 1652, Captain James Hind, royalist and notorious highwayman, climbed the scaffold and addressed the gathered crowd. With his typical courage, he pledged his continued loyalty to the King. His last words were, “I value it not threepence to lose my life in so good a cause. God’s will be done. If it were to do again, I protest I would do the like.”

So ended the life of Captain James Hind, Royalist Highwayman.

This is an Editor's Choice and was originally published on November 3, 2014.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Cryssa Bazos is an award winning historical fiction writer and 17th century enthusiast with a particular interest in the English Civil War. Her debut novel, Traitor's Knot, is published by Endeavour Press and placed 3rd in 2016 Romance for the Ages (Ancient/Medieval/Renaissance).

Late one Sunday night on November 9, 1651, a company of dragoons descended upon a barber’s house on Fleet Street to arrest one of his lodgers. The soldiers burst into the man’s quarters, pistols drawn, and hauled him to the Speaker of the House of Commons, William Lenthall. The next day, they brought their prisoner to Whitehall to be questioned.

The state had finally captured Captain James Hind, notorious highwayman, but their interest in him went beyond common thievery. He had become a political figure.

|

| James Hind by Unknown artist. NPG D29227 (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) |

The seeds of Hind’s nefarious career had started in the local grammar school. His father had recognized his son’s sharp mind and diverted a portion of his income to educate the boy. Unfortunately, Hind preferred the study of pranks to letters, and he loved tales of high adventure, particularly crime stories. By the age of fifteen, Hind had outstayed his welcome in school. His father apprenticed the lad to a butcher, but subservience did not suit Hind. Fed up by the beatings he received for his impertinence, he ran away to London.

Imagine the world of corruption that suddenly opened up for this clever Chipping Norton lad: drinking, carousing, and visiting houses of ill repute (he hadn’t married to Margaret yet). His life took on a new direction, or rather an inevitable one, when he met Thomas Allen in a holding cell following a drunken spree. Allen, also known as Bishop Allen, led a gang of highwayman working the London suburbs. Allen took the young Hind under his wing and introduced him to life on the highway.

During his coming-out robbery at Shooter’s Hill, Hind held up a gentleman and stole £10. To the dismay of his new crew, he returned part of the booty, a sum of forty shillings, to see the gentleman safely back to London.

Hind’s wit and generosity became his calling card and he developed a reputation as a gentleman robber, often jesting with his “clients” and giving good sport. Not surprising many of his exploits had a Robin Hood feel to them. Once, when travelling through Warwickshire, Hind came upon two bailiffs and a usurer who were trying to collect from an innkeeper a debt of £20. Hind intervened to save the landlord and settled the bond on his behalf. After the bailiffs received their due, Hind ambushed the usurer and stole back not only his £20 but also another twenty for good measure. When he returned to the inn, he gave the innkeeper £5 and said that he “had good luck by lending to honest men.”

|

| James Hind by Unknown artist. NPG D29226 (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) |

Following the end of the second civil war (1647-48), Hind began to operate alone, for sometime in 1648, Allen and most of his crew were captured after a foiled attempt to assassinate Oliver Cromwell. Hind had managed to escape and returned to highway robbery with a new purpose: harassing Roundheads, and his preferred quarry were regicides when he could get them.

According to legend, Hind held up the man who presided over the King’s trial, a regicide by the name of John Bradshaw. Hind caught the judge on the road in Dorsetshire. When Bradshaw tried to intimidate the highwayman with his reputation, Hind retorted, “I have now as much power over you as you lately had over the King, and I should do God and my country good service if I made the same use of it.”

Hind had become more than a highwayman; he was now a symbol of resistance for the Royalists and a burr in the saddle of Parliament. But he didn’t stop there. At one point, he must have realized that he could contribute more to the Crown than stealing from Roundheads.

On May 2, 1649, Hind sailed for The Hague and stayed there for three days before continuing to Ireland laden with the “King’s goods”, supplies destined for the Royalists' resistance against Cromwell. Not surprising, the Earl of Northampton, William Compton’s eldest brother, spent his exile in The Hague.

Hind remained in Ireland for nine months and served as corporal in the Marquess of Ormonde’s Life Guard. He eventually arrived in Scotland and presented himself to Charles Stuart. In Hind’s declaration, he “sent a letter to His Majesty acquainting His Highness of my arrival, and represented my service, &c, which was favourably accepted of, for no sooner had the King notice of my coming but immediately I had admittance to his chamber and kissed his hand.”

While Charles may have been desperate for men, this special treatment stands out as unusual. Were the King’s actions a result of his relief over receiving the services of a courageous, resourceful soldier or had Hind arrived with a recommendation? Though naturally audacious, that he dared send a letter to the King suggests he expected to be received.

Hind joined the King’s army and stayed with him through the invasion of England in August 1652, which ended with defeat at the Battle of Worcester on September 3, 1652. At the battle, Hind “kept the field until the King was fled” then headed for the anonymity of London, lying under hedges and in woods. When he arrived in London, rumours were already circulating that the infamous highwayman, Captain Hind, had helped the King escape Worcester. He managed to elude capture for five weeks, but eventually the dragoons found and arrested him.

Over the next several months, Hind went through three sensational trials. The bizarre twists would have today earned him round the clock media coverage.

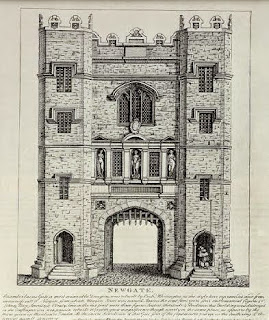

His first trial occurred on Dec 12, 1651 at the Old Bailey. Hind admitted to a few ‘pranks’ and even confessed to fighting with the King at Worcester. Though they could have charged him with High Treason, no Bill of Indictment or witnesses were brought against him. But he remained in close custody at Newgate.

|

| "Old Newgate". Licensed under Public domain via Wikimedia Commons |

Hind’s second trial was held in Reading on March 1, 1652. The state charged him with the murder of a local man who had once tried to stop Hind in Maidenhead Thicket. In fact, this was the only reported murder attributed to him throughout his long career as a highwayman. Hind stated that he fired on the man in self-defence.

At this point, Hind claimed benefit of clergy, a legal loophole that dated back to 1170 when the clergy were considered outside the jurisdiction of secular courts. To succeed, the defendant would need to read the scripture given to him (because in the 12th century, few except the clergy could read). Unfortunately, Hind failed the test, and they sentenced him to death. He must have regretted not applying himself better in school.

But reprieve came from the most unlikely source. The next day, before the sentence could be carried out, the Act of Oblivion came into force. The Act allowed for many crimes committed prior to September 3, 1651 (the Battle of Worcester) to be pardoned as an act of war, all except High Treason.

Now Parliament became desperate. Chapbooks and broadsheets tallying Hind’s exploits flooded London. One local publisher even released The Declaration of James Hind, an official account of his service to the King. All this publicity made Parliament look bad.

The gloves came off. The state turned to the Act of Oblivion for their cue and indicted Hind with High Treason for his participation at Worcester. For Parliament, the third trial was the charm. The court found Hind guilty and sentenced him to be hanged, drawn and quartered.

On September 24, 1652, Captain James Hind, royalist and notorious highwayman, climbed the scaffold and addressed the gathered crowd. With his typical courage, he pledged his continued loyalty to the King. His last words were, “I value it not threepence to lose my life in so good a cause. God’s will be done. If it were to do again, I protest I would do the like.”

So ended the life of Captain James Hind, Royalist Highwayman.

This is an Editor's Choice and was originally published on November 3, 2014.

References:

· Declaration of Captain James Hind, printed for G. Horton 1651

· The Adventures of Captain James Hind of Chipping Norton: The Oxfordshire Highwayman by O.M. Meades

· No Jest like a true Jest

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Cryssa Bazos is an award winning historical fiction writer and 17th century enthusiast with a particular interest in the English Civil War. Her debut novel, Traitor's Knot, is published by Endeavour Press and placed 3rd in 2016 Romance for the Ages (Ancient/Medieval/Renaissance).

For more stories, visit her blog cryssabazos.com or connect with her through Facebook, Twitter (@cryssabazos) or Instagram.

Traitor’s Knot is available:

eBook through Amazon. http://mybook.to/TraitorsKnot

Paperback through Amazon US (including Canada) http://amzn.to/2sgTpYv, or Amazon UK http://amzn.to/2sr5ASt

eBook through Amazon. http://mybook.to/TraitorsKnot

Paperback through Amazon US (including Canada) http://amzn.to/2sgTpYv, or Amazon UK http://amzn.to/2sr5ASt

Remarkable story and good material for a novel.

ReplyDeleteGreat research and read.

ReplyDeleteThank you very much Aimee!

Delete