The term “medieval castle” brings immediately to mind images of high castellated walls, massive gatehouses and vast keeps, and many such fortresses did indeed exist. The vast majority of castles were however much smaller structures – “strongholds” – built for local defence, even if on occasion they did serve as royal residences. One such is King John’s Castle, near Odiham, Hampshire. Though it is little more than a ruined shell today it has a most spectacular history and provides insights into what many more like it looked like.

.JPG) |

| The remains of King John's Castle today |

The castle consisted of a single massive octagonal keep of three stories and was surrounded by one or possibly more deep moats, which survive today only as dry, overgrown ditches. The walls, with cores of flint boulders held together by mortar, were externally clad with stone. This has however been stripped away over the centuries since here, as elsewhere in Britain, neighbouring communities exploited it as a quarry after it had been abandoned.

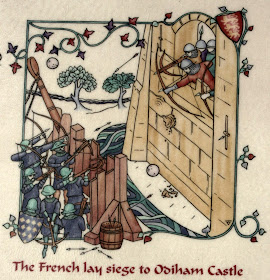

Now only the cores remain and indeed two sides of the octagon are gone completely. The site is preserved by Hampshire County Council as well as is possible given the castle’s ruined condition. A number of very informative notices are provided, each featuring delightful illustrations in the medieval style by the artist Andy Bardell. Some are shown here.

Now only the cores remain and indeed two sides of the octagon are gone completely. The site is preserved by Hampshire County Council as well as is possible given the castle’s ruined condition. A number of very informative notices are provided, each featuring delightful illustrations in the medieval style by the artist Andy Bardell. Some are shown here.

The structure was built in the 1207-1214 period on the orders of King John, a monarch who has had a deservedly bad reputation, as compared with his older brother Richard, who had an undeservedly good one. John’s entire reign consisted of conflicts with the Church, with the French and with his own barons. The castle at Odiham is associated with the single most important event of John’s reign, as it was from here in 1215 that he rode to Runnymede, under pressure from his rebellious barons, to sign the Magna Carta, and thereby to lay the foundation for the liberties of the English-speaking world in centuries to come.

|

| King John rides out to Runneymede |

A year later invading French troops besieged the castle for two weeks. The defenders were allowed to surrender with honour and were found, to the amazement of the French, to consist of fourteen men only. This is a commentary on just how invulnerable such structures were in the days before gunpowder and when hunger and thirst were the most effective weapons against determined defenders.

King John’s young son, Henry III, ordered repairs to the castle in 1225, the refurbished roof being of lead and weighing some 22 tons. It was supported by the outer walls and by a central column that no longer exists. On each of the two floors above ground level, beams extended from this central beam, like spokes of a wheel, to joist holes in the outer walls.

Eleven years later Henry III gave the castle to his younger sister, Eleanor, who was married to the powerful French nobleman, Simon de Montfort. He in due course became Earl of Leicester and was a key figure in the “Barons’ War” against his royal brother-in-law. While a residence in this period, the castle’s interior was likely to have been richly furnished. It can only however have been very cramped by modern standards and one assumes that most of the retainers and servants were lodged in smaller dwellings, of which no trace now remains, in the area between the castle walls and the moat.

|

| Eleanor and Simon prepare for a banquet (note Eleanor's household roll) |

This period ended when Simon de Montfort was killed in 1265 at the Battle of Evesham, in which he was fighting the future King Edward I, son of Henry III. Family ties notwithstanding, Eleanor was exiled to France, where she spent the rest of her days, taking with her the household rolls, which give an insight to life at the castle and which can be seen in Andy Bardell’s illustration.

Edward succeeded his father in due course and spent Christmas 1302 there. His own son, Edward II, proved to be one of the most disastrous kings in English history and his reign was not only marred by civil war but by his ultimate overthrow by his wife, Isabella, abetted by her lover. Odiham Castle was once more besieged in 1322, but again survived.

Edward succeeded his father in due course and spent Christmas 1302 there. His own son, Edward II, proved to be one of the most disastrous kings in English history and his reign was not only marred by civil war but by his ultimate overthrow by his wife, Isabella, abetted by her lover. Odiham Castle was once more besieged in 1322, but again survived.

Edward III, unlike his father, proved to be perhaps the most powerful English king of the medieval period and he not only initiated the Hundred Years War against France but scored notable victories over the Scots, Scotland at that time still being an independent kingdom, and almost invariable an ally of France. Edward granted Odiham Castle to his queen, Phillippa of Hainault, and it appears that she may have had a garden planted around it, an indication that its role was no longer primarily military.

|

| Edward III and Phillippa prepare for bed |

The castle was to play its last significant role in history in this period. In 1346 Edward’s army smashed an invading Scots force at Neville’s Cross (today a suburb of Durham) and in the process captured the Scottish king, David II. Held captive until an enormous ransom of 100,000 marks was paid, Davis was held for part of the time at the Tower of London, and for three years at Odiham. Here, in the agreeable rural surroundings of East Hampshire, he was provided with a well-furnished room and with good food, wine and other luxuries. The nature of his detention was unlikely to have been rigorous since honour would forbid escape prior to payment of ransom and one can well imagine David hunting in the surrounding area.

With David’s release Odiham Castle, now relegated to the status of a hunting lodge, started to fade from history. By 1600 it seems to have been in ruins and the process of quarrying it for stone seems to have started. Its day had however been a long one and despite its small size it was witness to some of the most dramatic events of England’s Middle Ages.

.JPG) |

| Odiham Castle today |

A particularly attractive way to reach the castle today is by barge from the nearby modern village of Odiham, and the photograph below shows a lucky group en route to King John's Castle in August 2013.

In preparing this article I am indebted to the splendid notices posted by Hampshire County Council at the site and which are so beautifully enhanced by Andy Bardell’s illustrations.

~~~~~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~~~~~

An Editor's Choice, originally published on September 9, 2013

~~~~~~~~~~~~

Antoine Vanner had had an adventurous and rewarding life, living and working long-term in eight countries and doing short-term assignments in many more. He is fascinated by history, especially of the nineteenth century, and this provides the foundation for his Dawlish Chronicles novels, the first of which, Britannia's Wolf was published early in 2013. Volume 5, Britannia's Amazon, was published in November 2016. He maintains a very extensive website: www.dawlishchronicles.com.

.JPG)

This was very readable and interesting. I particularly liked the illustrations. Many thanks.

ReplyDeleteGood site. Great pictures. Thanks.

ReplyDeleteThank You very much for a very informative and enjoyable article. The pics were great but the information was very well worth reading by all. Keep up the great work.

ReplyDeleteWonderful information, intriguing to read.

ReplyDeleteI'm glad you enjoyed it Margritte - it's the focus of one of my favourite walks. History comes alive in such places.

DeleteRegards: Antoine

Fascinating look at this castle's role in history. Wish I could visit the location!

ReplyDelete