Too often, when we consider Queen Victoria, we consider the Widow of Windsor dressed in black, or, if we're in a romantic mood, Albert's young bride. It's easy to forget that she was once a little girl, and a singularly isolated and put-upon one at that. One constant through her childhood, youth and young married life was Louise Lehzen. Lehzen was first her governess and protector, then her lady-attendant and only friend. Lehzen was one of the very few people around Victoria who was motivated solely for the love of and best interest of Victoria herself. In return, she has gone down in history as a strong influence on the queen during the first several years of her reign.

Louise Lehzen was born October 3, 1784 to Joachim Friedrich Lehzen, a distinguished Lutheran pastor, and his wife Melusine Palm in Hanover. At birth, her name was recorded as Johanna Clara Louise Lehzen. She was the youngest of nine children. Available data indicates that family finances required her to go to work as early as possible. There is little information about her schooling, but she was reputed to be at least adequately educated, possibly at home by her father. Her first situation was that of governess to the daughter of Baron von Marenholtz in Brunswick. In this position, she was treated as a member of the family, and was valued for her knowledge, excellent character and behaviour. This period of employment resulted in excellent references.

In 1818-1819, Lehzen entered the household of Princess Marie Luise Victoire of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, widowed Princess of Leiningen who married Edward, Duke of Kent (fourth son of George III), to serve as governess of the princess’s 12-year-old daughter Princess Feodora of Leiningen. (Known as Victoire, the new duchess was the sister of Prince Leopold, the Prince Regent’s son-in-law.) Victoire obligingly became pregnant, and Edward was determined that his child would be born in England. The household (including a midwife) was moved to London when Victoire was almost due to give birth. Her son Charles (Carl), now Prince of Leiningen, had to stay behind.

Princess Alexandrina Victoria was born in Kensington Palace May 24, 1819, fifth in line to the throne. She was not yet considered a real contender for the throne, as George III was still living and had three living sons ahead of her father. (Princess Charlotte, daughter of the Prince of Wales, had died at age 21 in 1817.) However, she was ahead of two uncles, younger than her father, who were eligible for the throne: Ernest, Duke of Cumberland, and Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge, both of whom had sons named George close in age to Alexandrina. The birth of Alexandrina Victoria stirred up a great deal of bad feelings between the Prince Regent, her father and the other brothers, resulting in Edward and his family being somewhat isolated from the royal family. This, in turn, allowed the child’s parents, and in particular her mother, to have greater opportunity to make their own decisions concerning her care.

Edward died in January 23, 1820, leaving his wife as sole guardian of Alexandrina, an unusual arrangement. His friend, Captain John Conway, was one of the executors of Edward’s will and became comptroller of his widow’s household.

|

| Princess Victoria Aged 4 by Stephen Poyntz Denning, 1823 |

When George III died January 29, 1820, his eldest son George, Prince of Wales and Prince Regent, became king as George IV. Neither he nor his next two surviving brothers had living children, and the little girl was now fourth in the succession. George IV resented that she was potentially an heir to the throne as he intensely disliked the Duke and Duchess of Kent and Prince Leopold, and preferred that his niece Alexandrina live in seclusion. As when her first husband died, the Duchess of Kent inherited debts so she and her children were virtually destitute. The Duchess of Kent was reliant on her brother Prince Leopold, his man of business Baron Christian Stockmar, and Captain John Conroy. While Leopold, and Stockmar, assumed direction of the duchess’s affairs, they were frequently absent due to political matters. As a potential heir to the throne, Alexandrina Victoria needed to stay in England. Leopold helped the duchess get permission to have Edward’s rooms in Kensington Palace, gave her an income, and helped her get loans to establish her household. Conroy stayed with the household, and the duchess became very dependent on him.

When Conroy became comptroller, he took control of all of the finances for Duchess of Kent and her daughters. Neither George IV nor any of the royal family provided any financial assistance. (George IV basically snubbed the child and her mother, and would have been delighted had they moved to Germany as dependents of Prince Leopold.) While in Kensington Palace, Conroy met and befriended Princess Sophia, George IV’s sister. It is believed Conroy guaranteed the Duchess of Kent’s debts (which were huge) with his own fortune and kept her creditors at bay in exchange for the duchess’s promise of reimbursement when her daughter inherited the throne. (Obviously, they were playing a long game.) He also acted as her secretary and general factotum. The Duchess of Kent was determined to devote herself exclusively to the raising of Alexandrina. Under the “Kensington system,” Alexandrina was never allowed to be alone; she slept in her mother’s room, she was never allowed to talk to anyone without a third party present (usually her mother or Lehzen), and was continually monitored. She was isolated from the outside world. She had only occasional visits from children from outside of the household. Her sister Feodora was her only friend, and the sisters were very close in spite of the age difference. Household rules required that employees not maintain diaries or mention household matters in correspondence (Lehzen complied). Conroy’s family was in the household, and his children, particularly his daughter Victoire who was about Alexandrina’s age, were thrust on her frequently. She did not like or trust Victoire (or anyone connected to Conroy) and deeply resented having his family forced on her.

When Mrs. Brock, Alexandrina Victoria’s nurse, was dismissed in 1824, Lehzen became governess to Alexandrina Victoria (at age 17, apparently Princess Feodora no longer needed a governess). The Duchess of Kent and Conroy, her comptroller, appointed her to this position because they assumed, as a dependent in a foreign country, she would be submissive and obedient to their instructions. Lehzen read to Alexandrina, and worked hard to engage her attention on her studies. Available data indicates that Lehzen was considered stern in appearance (pictures show an attractive woman) and quite disciplined; young Alexandrina was in awe of her new governess. Sources indicate that Lehzen gave Alexandrina a good grounding in the basics. More to the point, Lehzen worked with the Duchess of Kent, and became extremely close to Alexandrina. Lehzen and Alexandrina spent a great deal of time alone. The education envisioned by the duchess (and Conroy) was not the education of one expected to rule a kingdom, but was similar to that of the duchess herself or any other well-born girl, emphasizing accomplishments rather than real knowledge. Lehzen avoided the infighting of the household and focused on Alexandrina. She was firm with the child, and earned her respect. She devoted herself to Alexandrina; the two spent hours together, reading, making dolls (dressing them, naming them and imagining lives for them), forging a closeness that resulted in Alexandrina considering her a second mother. It speaks volumes for Lehzen’s tact and discretion that she outlasted George IV’s threat to send her back to Germany, avoided arousing the jealousy of the Duchess for her closeness to the child and avoided (for the most part) hostilities with Sir John Conroy. It seems clear that Lehzen’s primary functions were basic education and personal care for the child. It’s to Lehzen’s credit that, working within the “Kensington system”, she was able to meet the Duchess’s requirement that Alexandrina never be left alone without incurring Alexandrina’s resentment. Her loyalty to Alexandrina, and Alexandrina’s trust in her, became absolute.

When Alexandrina Victoria became undoubted heiress to the throne, George IV grew concerned about her education. Alexandrina spoke German with her mother and Lehzen and knew English. In 1825, he requested that Parliament grant an additional 6000 pounds per year each to Alexandrina and to her cousin George Cumberland specifically for their education. In 1827, George IV appointed Rev. George Davys to be Victoria’s tutor, at which point her more formal education began. His lessons included religion, ancient history and Latin. It’s important to note that Alexandrina had other tutors (she was taught French and Italian, penmanship, dancing, piano and singing; she was taught to draw by Richard Westall, R.A., and enjoyed mathematics).

Victoria considered Lehzen her only friend and intimate. Lehzen had unparalleled access and a definite influence over Victoria, that was maintained until Victoria’s marriage to Albert in 1840. Lehzen had envisioned Victoria ruling unmarried, as another Virgin Queen, and did not approve of her marriage. Lehzen did not think Albert was a good choice for Victoria’s consort. She particularly disapproved of Albert’s lack of position, money and influence; he gave nothing and received everything in her view. She was also jealous of Victoria’s love for Albert. Albert, in turn, disliked Lehzen and her continued influence over Victoria, considering her a servant who did not know her place and who was interfering in his marriage. Lehzen blocked various changes in the household that Albert wanted to make, and was not above going to the queen over his head. He in turn was jealous and resented Lehzen’s influence and Victoria’s reliance on her. (He wanted to be the head of his household, and had ambitions of his own, which required that he have Victoria’s full trust and dependence. Lehzen encouraged Victoria’s independence as queen.)

Albert got along with the Duchess of Kent, and supported a rapprochement between her and her daughter; he did not approve of Victoria’s intimacy with a servant and encouraged her to improve her relationship with her mother. He particularly resented Lehzen’s control spreading into various areas of the household over the heads of those appointed, especially the nursery. He had definite ideas of how he wanted his children raised, and they did not include Lehzen. A power struggle ensued between Albert and Lehzen, which was only resolved when Victoria’s and Albert’s first child became ill and almost died in the care of Dr. John Clark (court physician and part of the Flora Hastings case) who was summoned by Lehzen. Torn between Albert and Lehzen, Victoria finally conceded to Albert and Lehzen was let go as a result of this situation.

Lehzen left court in September 1842, ostensibly for her health, and returned to Germany with a generous pension. She lived with her sister, until her sister’s death, after which she continued to support her sister’s children. In 1858, Victoria was in Hanover and Lehzen was on the train platform, waving as Queen Victoria’s train passed, which the queen acknowledged. Much has been made of her estrangement from Queen Victoria but, in fact, she remained in regular correspondence with the Queen, and was visited by the Queen on a couple of occasions.

Louise Lehzen died September 9, 1870 in Buckeburg, Schaumberger Landkreis, Lower Saxony and was buried in the Jetenberger Cemetery. On her monument (raised by Queen Victoria), her name was shown as “Louise Clara Johanna von Lehzen.” Victoria did not significantly repair her relationship with her mother until after the death of Sir John Conroy March 2 1854, long after Louise Lehzen had left court. It is worthy of note that, after the death of her mother, Victoria did not seem to have another intimate nurturing female relationship (other than with her daughters, which is different-she was queen and mother in those relationships). She relied on Albert for support and security, then John Brown, and then Abdul Karim (her Indian servant known as the Munshi). After all is said and done, Lehzen was her safest and most trusted female friend and mentor.

Sources include:

Erickson, Carolly. HER LITTLE MAJESTY The Life of Queen Victoria. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997.

Gill, Gillian. WE TWO: Victoria and Albert: Rulers, Partners, Rivals. (Kindle edition.) New York: Ballantine Books, an imprint of the Random House Publishing Group, 2009.

Images are all in the public domain, found in Wikimedia Commons.

Express.co.uk. “The Women Who Really Raised The Royals” by David Cohen. November 16, 2012. Here.

FamPeople.com. “Louise Lehzen, biography.” Here.

FindAGrave.com. “Louise Von Lehzen.” Posted by Dieter Bierkenmaier, April 27, 2013. Here.

Google Books. Lee, Sidney, Ed. DICTIONARY OF NATIONAL BIOGRAPHY. Supplement Vol. 3. “Victoria,” Pp. 389-500. New York: Macmillan Co. 1901. Here.

Google Books. ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information, 11th Edition, Vol. 28. “Victoria, Queen” by H. CH. (Hugh Chisholm). Pp. 28-37. New York: Encyclopaedia Britannica Company, 1911. Here.

The Esoteric Curiosa. Raising A Queen; An 1840's Thumbnail Of The Initial Lady Behind The Throne Of One Of Histories Greatest Monarchs; Johanna Clara Louise Lehzen, Better Known As Baroness Lehzen, Governess, Adviser & Companion To Her Imperial Majesty The Queen Empress, Victoria! November 12, 2013. Here.

Queen Victoria’s Scrapbook. A Letter to Queen Victoria from Baroness Lehzen from 1867. Here.

Victorian Gothic. “Louise Lehzen, Governess to Princess Victoria” April 9, 2011. Here.

Victoriana Magazine on-line. “Queen Victoria-A Very Naughty Princess.” July 13, 2014. Here.

Web of English History. “Louise Lehzen (c1784-1870)” by H. G. Pitt, 1993. Here.

Web of English History. “Sir John Ponsonby Conroy, first baronet (1786-1854)” by Elizabeth Longford, 1993. Here.

Wikiwand. “Louise Lehzen.” Here.

~~~~~~~~~~

Lauren Gilbert has a bachelor's degree in English, and a life-long love of reading. Her first published book, HEYERWOOD: A Novel, was released in 2011. Her second, A RATIONAL ATTACHMENT, is due out soon. She lives in Florida with her husband Ed. Visit her website here for more information!

When Conroy became comptroller, he took control of all of the finances for Duchess of Kent and her daughters. Neither George IV nor any of the royal family provided any financial assistance. (George IV basically snubbed the child and her mother, and would have been delighted had they moved to Germany as dependents of Prince Leopold.) While in Kensington Palace, Conroy met and befriended Princess Sophia, George IV’s sister. It is believed Conroy guaranteed the Duchess of Kent’s debts (which were huge) with his own fortune and kept her creditors at bay in exchange for the duchess’s promise of reimbursement when her daughter inherited the throne. (Obviously, they were playing a long game.) He also acted as her secretary and general factotum. The Duchess of Kent was determined to devote herself exclusively to the raising of Alexandrina. Under the “Kensington system,” Alexandrina was never allowed to be alone; she slept in her mother’s room, she was never allowed to talk to anyone without a third party present (usually her mother or Lehzen), and was continually monitored. She was isolated from the outside world. She had only occasional visits from children from outside of the household. Her sister Feodora was her only friend, and the sisters were very close in spite of the age difference. Household rules required that employees not maintain diaries or mention household matters in correspondence (Lehzen complied). Conroy’s family was in the household, and his children, particularly his daughter Victoire who was about Alexandrina’s age, were thrust on her frequently. She did not like or trust Victoire (or anyone connected to Conroy) and deeply resented having his family forced on her.

When Mrs. Brock, Alexandrina Victoria’s nurse, was dismissed in 1824, Lehzen became governess to Alexandrina Victoria (at age 17, apparently Princess Feodora no longer needed a governess). The Duchess of Kent and Conroy, her comptroller, appointed her to this position because they assumed, as a dependent in a foreign country, she would be submissive and obedient to their instructions. Lehzen read to Alexandrina, and worked hard to engage her attention on her studies. Available data indicates that Lehzen was considered stern in appearance (pictures show an attractive woman) and quite disciplined; young Alexandrina was in awe of her new governess. Sources indicate that Lehzen gave Alexandrina a good grounding in the basics. More to the point, Lehzen worked with the Duchess of Kent, and became extremely close to Alexandrina. Lehzen and Alexandrina spent a great deal of time alone. The education envisioned by the duchess (and Conroy) was not the education of one expected to rule a kingdom, but was similar to that of the duchess herself or any other well-born girl, emphasizing accomplishments rather than real knowledge. Lehzen avoided the infighting of the household and focused on Alexandrina. She was firm with the child, and earned her respect. She devoted herself to Alexandrina; the two spent hours together, reading, making dolls (dressing them, naming them and imagining lives for them), forging a closeness that resulted in Alexandrina considering her a second mother. It speaks volumes for Lehzen’s tact and discretion that she outlasted George IV’s threat to send her back to Germany, avoided arousing the jealousy of the Duchess for her closeness to the child and avoided (for the most part) hostilities with Sir John Conroy. It seems clear that Lehzen’s primary functions were basic education and personal care for the child. It’s to Lehzen’s credit that, working within the “Kensington system”, she was able to meet the Duchess’s requirement that Alexandrina never be left alone without incurring Alexandrina’s resentment. Her loyalty to Alexandrina, and Alexandrina’s trust in her, became absolute.

|

| Baroness Louise Lehzen, drawn by Princess Victoria 1835 |

At the request of his sister Princess Sophia, George IV made Lehzen a baroness in the kingdom of Hanover, to reconcile Lehzen to this appointment. (Captain Conroy became Sir John Conroy, Knight Commander of the Hanoverian empire, at this time as well, also at Princess Sophia’s request.) There are suggestions that Lehzen’s elevation was designed to eliminate “commoners” from serving the princess, as well as to ameliorate any disappointment.

Lehzen remained with Alexandrina as lady-in attendance, and cooperated with Rev. Davys and the other tutors. Princess Sophia had previously given Conroy an estate worth 18,000 pounds in 1826. Alexandrina experienced a great loss when Feodora married Ernst, Prince of Hohenlohe-Langenburg, in 1828. (Feodora was eager to leave Kensington Palace and Conroy.) Alexandrina and her sister remained close throughout their lives. When Alexandrina Victoria reached the age of 10, she became known as Victoria. During these years, as the Duchess became more dependent upon him and he obtained more and more authority, Sir John Conroy became more overbearing and arrogant, looking for slights and determined, with the Duchess, to control Victoria.

George IV died June 26, 1830 and was succeeded by his brother William, who reigned as William IV. William and his wife Adelaide had always been fond of Victoria. Unfortunately, the duchess and Conroy immediately created friction and bad feeling by demanding more money, more prestige, formal recognition of Victoria as heir apparent, and that the duchess be made her regent. These demands offended William IV, and made him suspicious not only of the duchess and Conroy, but of Victoria herself. He was not comfortable in his role as king, preferring a simple life, and found the duchess and Conroy a great and perpetual vexation. The Duchess of Kent, in her turn, prevented Victoria from participating in the coronation procession and ceremony.

George IV died June 26, 1830 and was succeeded by his brother William, who reigned as William IV. William and his wife Adelaide had always been fond of Victoria. Unfortunately, the duchess and Conroy immediately created friction and bad feeling by demanding more money, more prestige, formal recognition of Victoria as heir apparent, and that the duchess be made her regent. These demands offended William IV, and made him suspicious not only of the duchess and Conroy, but of Victoria herself. He was not comfortable in his role as king, preferring a simple life, and found the duchess and Conroy a great and perpetual vexation. The Duchess of Kent, in her turn, prevented Victoria from participating in the coronation procession and ceremony.

At the king’s behest, Charlotte Percy, Duchess of Northumberland became Victoria’s official governess in 1831. Also in 1831, Prince Leopold, who had been less and less in sight, became king of Belgium, and Stockmar was needed in Coburg. Victoria was by this time aware that she was heir to the throne, and was increasingly confined. Lehzen continued to support and encourage her. Her mother and Conroy quarrelled with each other, and the pair of them continually quarrelled with the King, his ministers and the court at large. Victoria became skilled at hiding her feelings from her mother, Conroy and others in her household. The Duchess of Northumberland was dismissed in 1837 by the Duchess of Kent over her objections to the “Kensington system” and her refusal to submit to Sir John Conroy. Rev. Davys continued in his position until the death of William IV. Tensions and changes in the household strengthened the bonds between Victoria and Lehzen, and Lehzen’s influence. Lehzen encouraged Victoria to be informed and strong-minded, even though the Princess disliked learning. (Lehzen envisioned Victoria ruling as a strong, independent and unmarried queen.)

The duchess and Conroy continued their campaign to control Victoria. The duchess was determined to be appointed regent, in the event Victoria was under age when the king died, while Conroy had ambitions to be Victoria’s personal secretary and to have control over her, her household and her money. Conroy bullied the household, acting as master. Even as they quarrelled, the duchess did not prevent his domineering over Victoria.

The duchess and Conroy continued their campaign to control Victoria. The duchess was determined to be appointed regent, in the event Victoria was under age when the king died, while Conroy had ambitions to be Victoria’s personal secretary and to have control over her, her household and her money. Conroy bullied the household, acting as master. Even as they quarrelled, the duchess did not prevent his domineering over Victoria.

Victoria grew to hate Conroy and to deeply resent her mother for allowing him to abuse her. This resentment caused Victoria to withdraw into herself and created an estrangement between Victoria and her mother, long before the duchess was aware of it. Victoria was isolated except for Lehzen. In 1835, when Victoria was 16, she became ill typhoid and almost died. William IV was frail, and there were fears of his sanity. In an effort to establish his position firmly, Conroy went to Victoria as she lay extremely ill and tried to browbeat her into appointing him her personal secretary. When she refused, he brought her mother in to support his demands which Victoria continued to withstand. Angry and frustrated, Conroy apparently raged at both Victoria and Lehzen, for not giving in to his demands. This episode seems to have hardened her determination to stand her ground. She also began to read and study more on her own, preparing for her future. Even though her mother and Conroy continued their efforts, they were unable to shake her.

Now in her teens, Victoria knew her marriage was an issue of concern and speculation. At one point, she had said she would not marry, but it was considered essential that she marry a suitable consort. William IV favoured a match with her cousin George Cambridge and, in 1833, brought George and other potential acceptable suitors together at a ball for her birthday (she was 14 years old). German cousins also began appearing for consideration. Her mother and her Uncle Leopold were in favour of her marrying her cousin Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. She was in no hurry to decide. William IV was determined that he would choose a husband for Victoria and settled on Alexander of Orange, younger son of the Prince of Orange, and arranged for Alexander and his brother to come to England to meet Victoria in 1836. Unfortunately for the king’s plan, Victoria did not take to Alexander, especially in comparison to Albert and his brother Ernest, who met Victoria a short time later. Their visit lasted 3 weeks, at the end of which Victoria wanted Albert to be her husband, even though nothing was discussed or settled at the time. Lehzen and her Uncle Leopold were her only allies through this year, as her mother and Conroy continued their program of bullying and keeping Victoria under their control and badgering the king and court to acknowledge Victoria’s status.

William IV was bitterly aware of the Duchess of Kent’s ambitions to be regent and was determined to live until Victoria was 18 years old, and could inherit the throne without a regent. Victoria turned 18 on May 24, 1837. Despite being watched, she managed to meet with Lord Liverpool to discuss her situation. She also had the benefit of counsel from Baron Stockmar, sent by her Uncle Leopold to advise her. As always, Lehzen was present to support and encourage her in her stand against Conroy’s and her mother’s machinations. William IV died June 20, 1837, succeeding in thwarting the duchess’s (and Conroy’s) ambitions.

When the princess took the throne as queen, she took the name Victoria. Her first act, even before being crowned, was to have her bed removed from her mother’s room to her own room. Victoria relied on Lord Melbourne and on Lehzen for support. When Victoria moved to Buckingham Palace, Louise Lehzen accompanied her, acting as an unofficial personal secretary and unofficial head of Victoria’s household, with rooms adjoining the queen’s apartments. (Lehzen refused an official status.) Her mother had a suite of rooms much further away.

Conroy was dismissed from Victoria’s household, but continued to handle the duchess’s affairs. He was around on the duchess’s business but had no standing or influence at court, as Victoria banned him from approaching her. The duchess was present for the coronation but Conroy was not allowed to attend. Victoria acknowledged Lehzen during her coronation, and kissed Queen Adelaide and shook hands with her mother after the ceremony. Conroy was made a baronet in 1837, but the government (under Prime Minister Robert Peel) refused to create him an Irish peer. Conroy resigned his position with her mother in 1842 and left court. Victoria’s relationship with her mother improved slightly but remained distant due in part to the duchess’s continuing demands and complaints.

|

| Victoria, Duchess of Kent (1786-1861), mother of Queen Victoria, by Sir George Hayter, 1835 |

When the princess took the throne as queen, she took the name Victoria. Her first act, even before being crowned, was to have her bed removed from her mother’s room to her own room. Victoria relied on Lord Melbourne and on Lehzen for support. When Victoria moved to Buckingham Palace, Louise Lehzen accompanied her, acting as an unofficial personal secretary and unofficial head of Victoria’s household, with rooms adjoining the queen’s apartments. (Lehzen refused an official status.) Her mother had a suite of rooms much further away.

Conroy was dismissed from Victoria’s household, but continued to handle the duchess’s affairs. He was around on the duchess’s business but had no standing or influence at court, as Victoria banned him from approaching her. The duchess was present for the coronation but Conroy was not allowed to attend. Victoria acknowledged Lehzen during her coronation, and kissed Queen Adelaide and shook hands with her mother after the ceremony. Conroy was made a baronet in 1837, but the government (under Prime Minister Robert Peel) refused to create him an Irish peer. Conroy resigned his position with her mother in 1842 and left court. Victoria’s relationship with her mother improved slightly but remained distant due in part to the duchess’s continuing demands and complaints.

|

| John Conroy, British Army Officer and royal official by Alfred Tidey, 1836 |

Albert got along with the Duchess of Kent, and supported a rapprochement between her and her daughter; he did not approve of Victoria’s intimacy with a servant and encouraged her to improve her relationship with her mother. He particularly resented Lehzen’s control spreading into various areas of the household over the heads of those appointed, especially the nursery. He had definite ideas of how he wanted his children raised, and they did not include Lehzen. A power struggle ensued between Albert and Lehzen, which was only resolved when Victoria’s and Albert’s first child became ill and almost died in the care of Dr. John Clark (court physician and part of the Flora Hastings case) who was summoned by Lehzen. Torn between Albert and Lehzen, Victoria finally conceded to Albert and Lehzen was let go as a result of this situation.

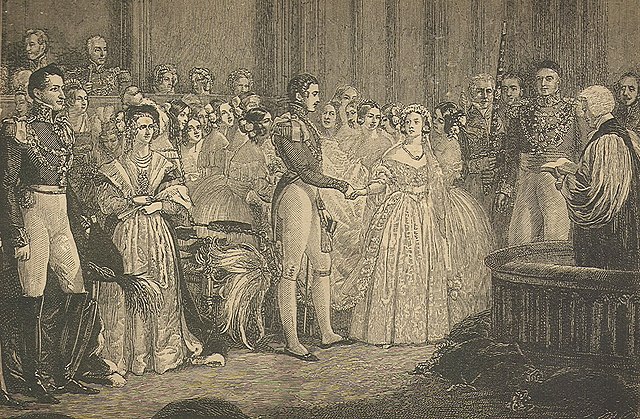

|

| Marriage of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. Engraving from the book "True Stories of the Reign of Queen Victoria" by Cornelius Brown, 1886 |

Louise Lehzen died September 9, 1870 in Buckeburg, Schaumberger Landkreis, Lower Saxony and was buried in the Jetenberger Cemetery. On her monument (raised by Queen Victoria), her name was shown as “Louise Clara Johanna von Lehzen.” Victoria did not significantly repair her relationship with her mother until after the death of Sir John Conroy March 2 1854, long after Louise Lehzen had left court. It is worthy of note that, after the death of her mother, Victoria did not seem to have another intimate nurturing female relationship (other than with her daughters, which is different-she was queen and mother in those relationships). She relied on Albert for support and security, then John Brown, and then Abdul Karim (her Indian servant known as the Munshi). After all is said and done, Lehzen was her safest and most trusted female friend and mentor.

|

| Baroness Louise Lehzen, Governess and Companion to Queen Victoria, by Koepke, 1842 |

Sources include:

Erickson, Carolly. HER LITTLE MAJESTY The Life of Queen Victoria. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997.

Gill, Gillian. WE TWO: Victoria and Albert: Rulers, Partners, Rivals. (Kindle edition.) New York: Ballantine Books, an imprint of the Random House Publishing Group, 2009.

Images are all in the public domain, found in Wikimedia Commons.

Express.co.uk. “The Women Who Really Raised The Royals” by David Cohen. November 16, 2012. Here.

FamPeople.com. “Louise Lehzen, biography.” Here.

FindAGrave.com. “Louise Von Lehzen.” Posted by Dieter Bierkenmaier, April 27, 2013. Here.

Google Books. Lee, Sidney, Ed. DICTIONARY OF NATIONAL BIOGRAPHY. Supplement Vol. 3. “Victoria,” Pp. 389-500. New York: Macmillan Co. 1901. Here.

Google Books. ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information, 11th Edition, Vol. 28. “Victoria, Queen” by H. CH. (Hugh Chisholm). Pp. 28-37. New York: Encyclopaedia Britannica Company, 1911. Here.

The Esoteric Curiosa. Raising A Queen; An 1840's Thumbnail Of The Initial Lady Behind The Throne Of One Of Histories Greatest Monarchs; Johanna Clara Louise Lehzen, Better Known As Baroness Lehzen, Governess, Adviser & Companion To Her Imperial Majesty The Queen Empress, Victoria! November 12, 2013. Here.

Queen Victoria’s Scrapbook. A Letter to Queen Victoria from Baroness Lehzen from 1867. Here.

Victorian Gothic. “Louise Lehzen, Governess to Princess Victoria” April 9, 2011. Here.

Victoriana Magazine on-line. “Queen Victoria-A Very Naughty Princess.” July 13, 2014. Here.

Web of English History. “Louise Lehzen (c1784-1870)” by H. G. Pitt, 1993. Here.

Web of English History. “Sir John Ponsonby Conroy, first baronet (1786-1854)” by Elizabeth Longford, 1993. Here.

Wikiwand. “Louise Lehzen.” Here.

~~~~~~~~~~

Lauren Gilbert has a bachelor's degree in English, and a life-long love of reading. Her first published book, HEYERWOOD: A Novel, was released in 2011. Her second, A RATIONAL ATTACHMENT, is due out soon. She lives in Florida with her husband Ed. Visit her website here for more information!

This was wonderful. So well-researched and thorough. I learned a lot.

ReplyDeleteAs did I Elizabeth; this held me spellbound.

DeleteAs did I Elizabeth, it held me spellbound.

Delete