By Lauren Gilbert

My husband and I went out to dinner this evening and really enjoyed it. Dining out is usually a pleasure, and it is something people have been doing for generations. Lists of places to eat were published in guide books and The Epicure's Almanack which was published in 1815. Dolly’s Chop House and Lloyd’s Coffee House were well known names. I ran across one named La Belle Sauvage Tavern (also known as the Bell Savage Tavern), located on Ludgate Hill, with a long and fascinating history. As you will see, La Belle Sauvage was much more than a place to eat.

There is a record of a forged claim by William Lawton for 20 shillings against William Savage in the area, which resulted in Mr. Lawton being sentenced to an hour in the pillory and establishes the name of Savage as that of a citizen there. During the reign of Henry VI, in 1453, a clause roll (or close roll-administrative records created by the royal chancery) refers to the bequest of Savage’s Inn, which would indicate the existence of an inn as early as the 15th century. The inn also seems to have been known at some point as the Bell in the Hoop. The inn was a coaching inn at this point. There is an indication that in 1554 Sir Thomas Wyatt came to the Bell Savage in Ludgate for his rebellion, stopped to rest, couldn’t get into the city (which ended his rebellion), and rested at the inn until he could turn himself in at Temple Bar. In 1568, John Craythorne gave the right to possess the property to the Cutler’s Company (knife makers’ guild).

By 1584, the inn was known as the Belle Sauvage. Plays were staged in the yard of certain inns during this period, and were staged at the Belle Sauvage, including a performance of Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus and (possibly) some of Shakespeare’s plays; there is an indication that Love’s Labours Lost was performed there. In 1616, John Rolfe and Pocahontas stayed at the Belle Sauvage during their visit from America. (Subsequently, there was a theory that the inn was named for her, but that was not correct as it was known as the Belle Sauvage or Bell Savage long before her arrival.) The original inn burned down in the Great Fire of London, but it was rebuilt. In 1703, the Belle Sauvage was mentioned in a newspaper article in relation to damage to the building resulting from a severe windstorm.

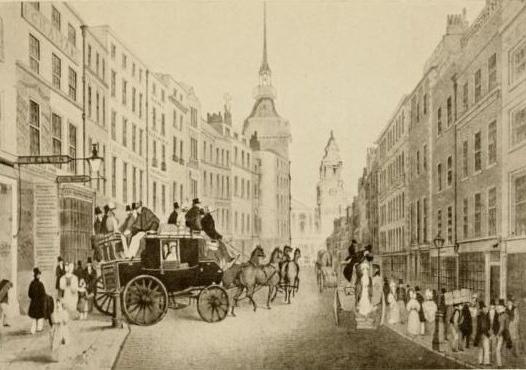

|

| La Belle Sauvage Inn, Ludgate Hill, London |

My husband and I went out to dinner this evening and really enjoyed it. Dining out is usually a pleasure, and it is something people have been doing for generations. Lists of places to eat were published in guide books and The Epicure's Almanack which was published in 1815. Dolly’s Chop House and Lloyd’s Coffee House were well known names. I ran across one named La Belle Sauvage Tavern (also known as the Bell Savage Tavern), located on Ludgate Hill, with a long and fascinating history. As you will see, La Belle Sauvage was much more than a place to eat.

There is a record of a forged claim by William Lawton for 20 shillings against William Savage in the area, which resulted in Mr. Lawton being sentenced to an hour in the pillory and establishes the name of Savage as that of a citizen there. During the reign of Henry VI, in 1453, a clause roll (or close roll-administrative records created by the royal chancery) refers to the bequest of Savage’s Inn, which would indicate the existence of an inn as early as the 15th century. The inn also seems to have been known at some point as the Bell in the Hoop. The inn was a coaching inn at this point. There is an indication that in 1554 Sir Thomas Wyatt came to the Bell Savage in Ludgate for his rebellion, stopped to rest, couldn’t get into the city (which ended his rebellion), and rested at the inn until he could turn himself in at Temple Bar. In 1568, John Craythorne gave the right to possess the property to the Cutler’s Company (knife makers’ guild).

By 1584, the inn was known as the Belle Sauvage. Plays were staged in the yard of certain inns during this period, and were staged at the Belle Sauvage, including a performance of Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus and (possibly) some of Shakespeare’s plays; there is an indication that Love’s Labours Lost was performed there. In 1616, John Rolfe and Pocahontas stayed at the Belle Sauvage during their visit from America. (Subsequently, there was a theory that the inn was named for her, but that was not correct as it was known as the Belle Sauvage or Bell Savage long before her arrival.) The original inn burned down in the Great Fire of London, but it was rebuilt. In 1703, the Belle Sauvage was mentioned in a newspaper article in relation to damage to the building resulting from a severe windstorm.

|

| La Belle Sauvage Inn and Yard |

The Belle Sauvage became one of the famous coaching inns. In 1674, with 40 rooms and facilities for 100 horses, it was quite an enterprise. By the Regency era, it had stabling for approximately 400 horses and was known for sending coaches all over the country. (The Belle Sauvage was one of two inns on the London to Bath route-by 1667, a stage left at 5:00 am every Monday, Wednesday and Friday, and travellers were told they would complete the 105 mile trip in three days if all went well.) Routes expanded and coaches from the Belle Sauvage went to Colchester, Ely, Holyhead, Shrewsbury, Warwick and Windsor, to name a few. The hostlers would have changed horses (a fresh team harnessed to a coach to replace an exhausted team) while passengers hopefully had time to dine (dinners had to be timed for a coach’s arrival), some stayed the night, possibly to be ready for an early departure, and so forth. It was one of the main inns for mail coaches and stage coaches coming into and leaving London. Its proximity to the Fleet Prison also brought a clientele for meals. (Prisoners had to pay for food and beverages. Lucky prisoners had family or friends willing to bring them meals or the means to pay a jailor to bring food; the Belle Sauvage was handy for such custom. Local businessmen and others with business in the area also dined there.)

What amenities might have been enjoyed at La Belle Sauvage? In general, coaching inns offered breakfast, dinner, supper, and liquid refreshment. According to The Picture of London, for 1803: Being A Correct Guide to All the Curiosities, Amusements, Exhibitions, Public Establishments, and Remarkable Objects, In and Near London, The Belle Sauvage had a good coffee room (dining room), newspapers, and access to coaches to and from many regions of England. The guide book indicates it was popular with travellers. The Epicure's Almanack; or Calendar of Good Living, published in 1815, includes the Belle Sauvage in its list of places to dine in the Fleet Market area. Commended for a “well stocked larder”(1), The Epicure's Almanack indicates that the Belle Sauvage was not only popular with travellers but others as well. It does not provide a description of meals serviced or specialties, but apparently the Belle Sauvage was not one of the inns known for meals served badly prepared or timed so that travellers could not enjoy them.

There are also literary references to the Belle Sauvage (or Bell Savage). Sir Walter Scott named “the famous Bell-Savage” (2) in Kenilworth in Chapter 13, the inn where Wyland and Tressilian stayed. Kenilworth was first published January 28, 1821 and is set in 1575. Another literary reference was established when Charles Dickens alluded to the Belle Sauvage in The Pickwick Papers. The novel is set in the years1827-1831 and was originally published in installments between March 1836-November 1837. It features a character named Tony Weller (father of Sam Weller) who was a coachman whose coach arrived in and departed from London at La Belle Sauvage. It was also linked with the magazine Punch (founded in 1841). The men who produced the magazine met weekly over dinner to discuss and debate various subjects, and the Belle Sauvage was supposedly the site of such a dinner, possibly the first (I was unable to find an exact date).

Trains had been on the horizon since the late 18th century and steam engines a subject of study and experimentation in the early 19th century. Development continued, and in 1830, the Liverpool to Manchester route opened. The 1840’s saw a huge growth in the railroad systems (by 1844, over 2000 miles of line had been established) and, as the routes expanded, the need for coaching service diminished. Railroad travel was faster and provided more efficient service for the mail. As the coaching routes were no longer needed, coaching inns no longer drew customers. The railroad era finally put an end to La Belle Sauvage and, in 1873, it was torn down to allow for construction of a railway viaduct.

What amenities might have been enjoyed at La Belle Sauvage? In general, coaching inns offered breakfast, dinner, supper, and liquid refreshment. According to The Picture of London, for 1803: Being A Correct Guide to All the Curiosities, Amusements, Exhibitions, Public Establishments, and Remarkable Objects, In and Near London, The Belle Sauvage had a good coffee room (dining room), newspapers, and access to coaches to and from many regions of England. The guide book indicates it was popular with travellers. The Epicure's Almanack; or Calendar of Good Living, published in 1815, includes the Belle Sauvage in its list of places to dine in the Fleet Market area. Commended for a “well stocked larder”(1), The Epicure's Almanack indicates that the Belle Sauvage was not only popular with travellers but others as well. It does not provide a description of meals serviced or specialties, but apparently the Belle Sauvage was not one of the inns known for meals served badly prepared or timed so that travellers could not enjoy them.

There are also literary references to the Belle Sauvage (or Bell Savage). Sir Walter Scott named “the famous Bell-Savage” (2) in Kenilworth in Chapter 13, the inn where Wyland and Tressilian stayed. Kenilworth was first published January 28, 1821 and is set in 1575. Another literary reference was established when Charles Dickens alluded to the Belle Sauvage in The Pickwick Papers. The novel is set in the years1827-1831 and was originally published in installments between March 1836-November 1837. It features a character named Tony Weller (father of Sam Weller) who was a coachman whose coach arrived in and departed from London at La Belle Sauvage. It was also linked with the magazine Punch (founded in 1841). The men who produced the magazine met weekly over dinner to discuss and debate various subjects, and the Belle Sauvage was supposedly the site of such a dinner, possibly the first (I was unable to find an exact date).

Trains had been on the horizon since the late 18th century and steam engines a subject of study and experimentation in the early 19th century. Development continued, and in 1830, the Liverpool to Manchester route opened. The 1840’s saw a huge growth in the railroad systems (by 1844, over 2000 miles of line had been established) and, as the routes expanded, the need for coaching service diminished. Railroad travel was faster and provided more efficient service for the mail. As the coaching routes were no longer needed, coaching inns no longer drew customers. The railroad era finally put an end to La Belle Sauvage and, in 1873, it was torn down to allow for construction of a railway viaduct.

Footnotes:

(1) The Epicure's Almanack: Eating and Drinking in Regency London, ed. Janet Ing Freeman, pp. 77-78.

(2) Scott, Sir Walter. Kenilworth. P. 171.

Sources include:

Feltham, John. The Picture of London, For 1803: Being A Correct Guide to All the Curiosities, Amusements, Exhibitions, Public Establishments, and remarkable Objects, in and Near London. 1802: R. Phillips, London). A Nabu Public Domain Reprint.

Rylance, Ralph. The Epicure's Almanack: Eating and Drinking in Regency London The Original 1815 Guidebook, edited by Janet Ing Freeman. 2013: British Library, London.

Scott, Sir Walter. Kenilworth. A. L. Burt Co, New York. (Publishing date is not shown; appears to have been published about 1926)

(1) The Epicure's Almanack: Eating and Drinking in Regency London, ed. Janet Ing Freeman, pp. 77-78.

(2) Scott, Sir Walter. Kenilworth. P. 171.

Sources include:

Feltham, John. The Picture of London, For 1803: Being A Correct Guide to All the Curiosities, Amusements, Exhibitions, Public Establishments, and remarkable Objects, in and Near London. 1802: R. Phillips, London). A Nabu Public Domain Reprint.

Rylance, Ralph. The Epicure's Almanack: Eating and Drinking in Regency London The Original 1815 Guidebook, edited by Janet Ing Freeman. 2013: British Library, London.

Scott, Sir Walter. Kenilworth. A. L. Burt Co, New York. (Publishing date is not shown; appears to have been published about 1926)

Elizabethan Era. “Bell Savage Inn” by L. K. Alchin. HERE

thestreetnames.com “Pocahontas and her London Street Name Connection,” Elizabeth Steynor, 1/13/2017, HERE; “La Belle Sauvage Yard, Pocahontas and a dancing horse,” Elizabeth Steynor, 5/18/2015 HERE; “London’s Coffee Connections,” Elizabeth Steynor, 9/29/2014 HERE

AnInkyTale.co.uk. “Proprietors of Punch Magazine” Jane E. Chadwick, September 26, 2016 HERE.

British Heritage Online. “Travel Through Time at England’s Coaching Inns” by Sean McLachlan, July 1, 2009. HERE

British History Online. Walter Thornbury, 'Ludgate Hill', in Old and New London: Volume 1 (London, 1878), pp. 220-233 HERE.

English Historical Fiction Authors. “Coaching Inns in Early 19th Century England” by Julie Klassen, December 12, 2016. HERE; “Lloyds--Lifeblood of British Commerce and Starbucks of Its Day” by Linda Collison, July 30, 2012. HERE

Google Books. 1607: Jamestown and The New World. Compiled by Dennis Montgomery. 2007: The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, VA, in association with Rowman & Littlefield, New York. P. 140. HERE; Holland, J. G. Scribner's Monthly, An Illustrated Magazine for the People. Vol. XXII. (May, 1881 to Oct. 1881, inclusive). "In and Out of London with Dickens." P. 39. 1881: The Century Company, New York HERE; Spielman, Marion Harry. The History of Punch 1895: Cassell and Company, Ltd., London. HERE

London Online. “La Belle Sauvage.” (No author or post date shown.) HERE

The Word Wenches. “Travelling the Roads of Regency England with Louise Allen!” March 4, 2015. HERE

Parliament.UK. “Railways in Early 19th Century Britain.” (No author or post date shown.) HERE

Wicked William. “Principal Departures for London Coaches (1819)” by Greg Roberts, April 28, 2016 HERE

Pictures: Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain) HERE and HERE.

Lauren Gilbert, author of Heyerwood, A Novel, lives in Florida with her husband. She is a long-time member of JASNA, and is also a member of the Florida Writer's Association. Her next novel, A Rational Attachment, is due out soon. Visit her website for more information HERE.

thestreetnames.com “Pocahontas and her London Street Name Connection,” Elizabeth Steynor, 1/13/2017, HERE; “La Belle Sauvage Yard, Pocahontas and a dancing horse,” Elizabeth Steynor, 5/18/2015 HERE; “London’s Coffee Connections,” Elizabeth Steynor, 9/29/2014 HERE

AnInkyTale.co.uk. “Proprietors of Punch Magazine” Jane E. Chadwick, September 26, 2016 HERE.

British Heritage Online. “Travel Through Time at England’s Coaching Inns” by Sean McLachlan, July 1, 2009. HERE

British History Online. Walter Thornbury, 'Ludgate Hill', in Old and New London: Volume 1 (London, 1878), pp. 220-233 HERE.

English Historical Fiction Authors. “Coaching Inns in Early 19th Century England” by Julie Klassen, December 12, 2016. HERE; “Lloyds--Lifeblood of British Commerce and Starbucks of Its Day” by Linda Collison, July 30, 2012. HERE

Google Books. 1607: Jamestown and The New World. Compiled by Dennis Montgomery. 2007: The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, VA, in association with Rowman & Littlefield, New York. P. 140. HERE; Holland, J. G. Scribner's Monthly, An Illustrated Magazine for the People. Vol. XXII. (May, 1881 to Oct. 1881, inclusive). "In and Out of London with Dickens." P. 39. 1881: The Century Company, New York HERE; Spielman, Marion Harry. The History of Punch 1895: Cassell and Company, Ltd., London. HERE

London Online. “La Belle Sauvage.” (No author or post date shown.) HERE

The Word Wenches. “Travelling the Roads of Regency England with Louise Allen!” March 4, 2015. HERE

Parliament.UK. “Railways in Early 19th Century Britain.” (No author or post date shown.) HERE

Wicked William. “Principal Departures for London Coaches (1819)” by Greg Roberts, April 28, 2016 HERE

Pictures: Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain) HERE and HERE.

Lauren Gilbert, author of Heyerwood, A Novel, lives in Florida with her husband. She is a long-time member of JASNA, and is also a member of the Florida Writer's Association. Her next novel, A Rational Attachment, is due out soon. Visit her website for more information HERE.

Wow! A Regency era Lonely Planet Guide! ;-)

ReplyDeleteOne of those EHA posts I read straight though,absolutely fascinating. Loved seeing the references. All that hustle and bustle from long ago, makes those time alive again! Thank you

ReplyDeleteand, in 1873, it was torn down to allow for construction of a railway viaduct.

well if it had to go, that was a fitting use for a site so dedicated to travel!

One of the joys of reading JAFF and Regency historical fiction is that it has drawn me into the actual history of the period. Another piece of useful and interesting information about the times. Fascinating write-up, Lauren.

ReplyDeleteMy great grandfather was born in the Belle Sauvage Yard in 1838. His father and father's business partner had an office/residence in the building.

ReplyDelete