While in his native England around 754, Saint Lebwin apparently resisted the call to be a missionary. His 10th century hagiography says God admonished him three times before he got on a boat and traveled to the Continent.

Lebwin’s life in England, including his birth date, is a mystery other than that he was educated in a monastery. His reluctance to leave his homeland is understandable. Travel was uncomfortable and hazardous, and when he got to his destination, he would be preaching to a stubborn audience of pagans. This line of work also was dangerous. Saint Boniface, a Saxon missionary from Britain, and his companions had recently been martyred by a mob of pagans in Frisia.

We don’t know what persuaded Lebwin to go. Maybe he believed that he would someday stand before God and be asked to account for all the souls he could’ve brought to Christ. If he neglected that duty, he would face consequences in the afterlife.

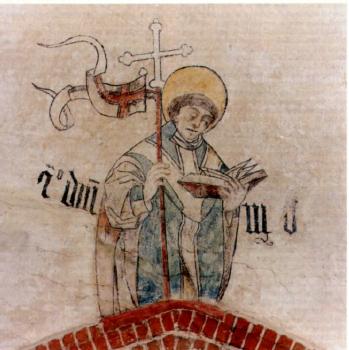

|

| Saint Lebwin, from a fresco painted before 1800 |

Lebwin’s ship sailed to Utrecht, close to Frisia, and he was greeted by Saint Gregory, who was serving as bishop. A disciple of Boniface since childhood, Gregory might still have been mourning his mentor when Lebwin related God’s command.

Gregory sent Lebwin and a companion to a settlement on the River IJssel, an area the Frisians and Continental Saxons disputed. Here, he enjoyed the hospitality of an aristocratic Saxon widow named Abachilda, and with her support, found fertile ground. At first, the faithful built a chapel on the river’s west bank. Then they built a church across the river in Deventer, which was perhaps a merchant town. It proved to be a good place of operation for Lebwin. He traveled into Saxon lands and gained many followers, including the nobleman Folcbert of Sudberg.

Converting an aristocrat helped keep a missionary safe, and if a leader converted, so might his followers. But pagans of all classes might fear divine retribution. They believed their survival in this world depended on pleasing their gods. So they would leave behind a few stalks of grain for the goddess responsible for the harvest and their ability to feed themselves through winter. Or they might sacrifice war captives as a thanksgiving to Wodan, the god who decided which side won wars. Baptismal vows required Christians to renounce Wodan and other deities. Not a big deal if that convert was a peasant or a slave, who by definition had little influence. But if the new Christian was someone who could order others to displease the old gods, the consequences were dire.

That might be why a mob burned Lebwin’s church in Deventer and caused his followers to scatter.

If the mob was trying to scare Lebwin away, they were sorely disappointed. Instead he was determined to speak at the annual assembly of Saxon leaders at Marklohe. The decentralized peoples had no king, but noblemen from the villages did choose someone to lead soldiers during wartime.

Folcbert tried to dissuade Lebwin, fearing the Englishman would be killed. In addition, the roughly three weeks to get to Marklohe had its own hazards such as bandits and otherworldly creatures. Lebwin would not be moved and was certain God would protect him. Frustrated by his friend’s refusal, Folcbert sent him away.

The assembly at first went as planned, with the pagans giving thanks to their gods, asking for protection of their lands, and gathering in a circle. Suddenly, Lebwin showed up at the meeting in his priestly garb, holding a cross in one hand and the gospel in the crook of his other arm. He prophesized that if the Saxons followed the Christian God’s command, they would be richly rewarded, and no king would rule over them. If they didn’t, he predicted, a king from a nearby land would conquer them, and they would lose everything, even their freedom.

|

| An 1869 illustration |

It’s a convenient prophesy, written well over 100 years after Charlemagne had subjugated the Saxon peoples and the Church, with the monarch’s support, had made every attempt to obliterate the old religion. Like their pagan counterparts, Christians believed their deity had a hand in everything, including who won the battle, and this literary device was a way to reinforce that faith would be rewarded while disobedience was punished.

But might there be a grain of truth? Might Lebwin have feared that God would blame him for the lost souls if he didn’t summon the courage to speak to Saxon leaders? Hard to say for certain.

If Lebwin addressed the assembly, he did not get the response he wanted. The pagans thought he was a charlatan preaching nonsense and wanted to kill him. Somehow Lebwin escaped. A Saxon chided those assembled for their lack of manners—they had respected foreign envoys—and made the case for Lebwin to be left alone. Apparently, the Saxon leaders agreed, and they went back to their normal business.

Lebwin returned to Deventer and had his church rebuilt. He died of natural causes around 770 and was entombed within the church.

Later, pagan Saxons destroyed the church again—we don’t know exactly when—and spent three days vainly looking for his body, if we are to believe the hagiography. Pagan Saxons, who burned their dead, might not have understood the significance of a saint’s relics. The fruitless search might have been a creative addition to show that pagans were ultimately on the losing side. They didn’t find the relics because God didn’t want them to.

|

| A mural from around 1880 depicting the destruction of the Irminsul. |

In 772, Charlemagne and his Frankish forces invaded Saxony, and reminiscent of Saints Boniface and Willibrord, demolished their sacred pillar, the Irminsul. The enmity between the Franks and the Saxons went back for generations even then, but this was the first time the conflict had a religious tone. Two summers later, while Charlemagne was at war (literally) with his ex-father-in-law in Italy, the Saxons retaliated, wrecking churches.

In 775, the same year Charlemagne’s army was again fighting the Saxons, Saint Ludger was sent to Deventer to restore the church and find Lebwin’s relics. According to the hagiography, Lebwin appeared to Ludger in a dream, telling him where to find his body. Ludger did as instructed and found the remains. He moved one of the building’s outer walls to make sure the saint would always be present in the church he had lived for.

All images are public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Sources

Medieval Sourcebook: The Life of Lebwin

"St. Lebwin" by Thomas Kennedy, The Catholic Encyclopedia

Charlemagne's Early Campaigns (768-777): A Diplomatic and Military Analysis, by Bernard Bachrach

Butler's Lives of the Saints, Volume 11, edited by Alban Butler, Paul Burns

The Barbarian Conversion: From Paganism to Christianity, by Richard A. Fletcher

~~~~~~~~~~

Kim Rendfeld learned about the Frankish-Saxon wars while writing her first novel, The Cross and the Dragon, in which a Frankish noblewoman must contend with a jilted suitor and the fear of losing her husband. Kim wrote her second book, The Ashes of Heaven's Pillar, about a Saxon peasant who will fight for her children after losing everything else, to provide a Saxon perspective on the events.

The Cross and the Dragon was rereleased Aug. 3, 2016, in print and ebook formats. You can order the book at Amazon, Kobo, iTunes, Barnes and Noble, Smashwords, CreateSpace, and other vendors.

The Ashes of Heaven's Pillar will be rereleased on Nov. 2, 2016. Preorders for ebooks are available at Amazon, Kobo, Barnes and Noble, and iTunes. It will also be published in print, and if you would like a note when it's available, email Kim at kim [at] kimrendfeld [dot] com.

The wars between the Franks and the Saxons play a major role in Kim's third novel, Queen of the Darkest Hour, about Charlemagne’s fourth wife, Fastrada.

Connect with Kim at on her website kimrendfeld.com, her blog, Outtakes of a Historical Novelist at kimrendfeld.wordpress.com, on Facebook at facebook.com/authorkimrendfeld, or follow her on Twitter at @kimrendfeld.

Kim Rendfeld learned about the Frankish-Saxon wars while writing her first novel, The Cross and the Dragon, in which a Frankish noblewoman must contend with a jilted suitor and the fear of losing her husband. Kim wrote her second book, The Ashes of Heaven's Pillar, about a Saxon peasant who will fight for her children after losing everything else, to provide a Saxon perspective on the events.

The Cross and the Dragon was rereleased Aug. 3, 2016, in print and ebook formats. You can order the book at Amazon, Kobo, iTunes, Barnes and Noble, Smashwords, CreateSpace, and other vendors.

The Ashes of Heaven's Pillar will be rereleased on Nov. 2, 2016. Preorders for ebooks are available at Amazon, Kobo, Barnes and Noble, and iTunes. It will also be published in print, and if you would like a note when it's available, email Kim at kim [at] kimrendfeld [dot] com.

The wars between the Franks and the Saxons play a major role in Kim's third novel, Queen of the Darkest Hour, about Charlemagne’s fourth wife, Fastrada.

Connect with Kim at on her website kimrendfeld.com, her blog, Outtakes of a Historical Novelist at kimrendfeld.wordpress.com, on Facebook at facebook.com/authorkimrendfeld, or follow her on Twitter at @kimrendfeld.

Truly fascinating account. It would have been easier to have returned home or not gone at all, and yet he found the courage to carry on. Thanks for sharing.

ReplyDelete