More than once I have heard medieval chroniclers affectionately, or not so affectionately, referred to as “lying toads.”

For some, the appearance of a few (or more than a few!) non-factual statements is reason to steer clear of these primary sources. Better to turn to the “experts”, the modern historians who have sifted the wheat from the chaff and can tell us what really happened.

This has always puzzled me. Certainly, the medieval chroniclers do tell a tall tale now and then, but there are far more important reasons to read them than to find out what actually happened. We need to find out what the medievals think happened. We need to find out why they think it happened. We need to study what they wrote as a means of studying them.

An example would be concerning the size of armies. Medieval chroniclers are notorious for inflating the size of armies when discussing a battle. But instead of throwing the book aside in disgust, it is worthwhile to contemplate why the numbers are inflated. What does this exaggeration tell us about the society in which the chronicle was penned? Is there a standard trope for describing battles that the writers are adhering to?

Because of these obvious inaccuracies, some historians are tempted to ignore the chronicles entirely and only use “official” sources for their research—purchase records of the king’s court, statutes enacted in important cities. In The Autumn of the Middle Ages, early twentieth-century historian Johan Huizinga warns against this, saying:

Medieval historians who prefer to rely as much as possible on official documents because the chronicles are unreliable fall thereby victim to an occasionally dangerous error. The [legal] documents tell us little about the difference in tone that separates us from those times; they let us forget the fervent pathos of medieval life…. This why the authors of the chronicles, no matter how superficial they may be with respect to the actual facts and no matter how often they may err in reporting them, are indispensable if we want to understand that age correctly.Another objection to using the medieval chronicles for research is that so often they don’t tell us the history that we’re interested in knowing. Sometimes what we consider the “real history” in chronicles will be blended with something else entirely. We have to skim through reams of non-pertinent information to get to the nuggets of fact about who ruled when and who fought whom.

But this presupposes that the things that are important to us today are the same things that should have been important to them then. The reams of “non-pertinent” information are things they wrote down on expensive parchment or vellum because they wanted them preserved for posterity.

Gildas was a sixth century monk who documented the Saxon invasions of Britain. He mentions Ambrosius Aurelianus, who is a piece of Arthurian legend. Frequently, scholars will pull these Arthurian fragments out of his work De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae and discard the rest as the crazy polemic of a bitter old monk.

But instead of skimming through all the “boring” parts where Gildas is blaming the Britons for their sins and explaining the Saxon invasion as a punishment for their iniquities, it is useful to consider why Gildas included this. What does it tell us about Gildas? Is he an anomaly in his society or is his line of reasoning shared by many?

Bede, in his Ecclesiastical History of England written a century and a half later, echoes Gildas’ sentiments, saying that the invasion of the Saxons was punishment on the Britons for not sharing the Gospel with other peoples. It seems that this subject was of prime importance to at least the monastic portion of society. Was this opinion shared by society at large?

When we accept medieval chronicles on their own terms, not blindly accepting every word as fact but also not casually dismissing everything we find wrong or irrelevant, that is when we truly begin to learn about the society in which these chronicles were written. When we extend them the same courtesy that we would to a living grandparent, sitting at their feet, learning about what was important to them in “the old days”, that is when we come across the nuggets of gold that we didn’t even know we were looking for.

____

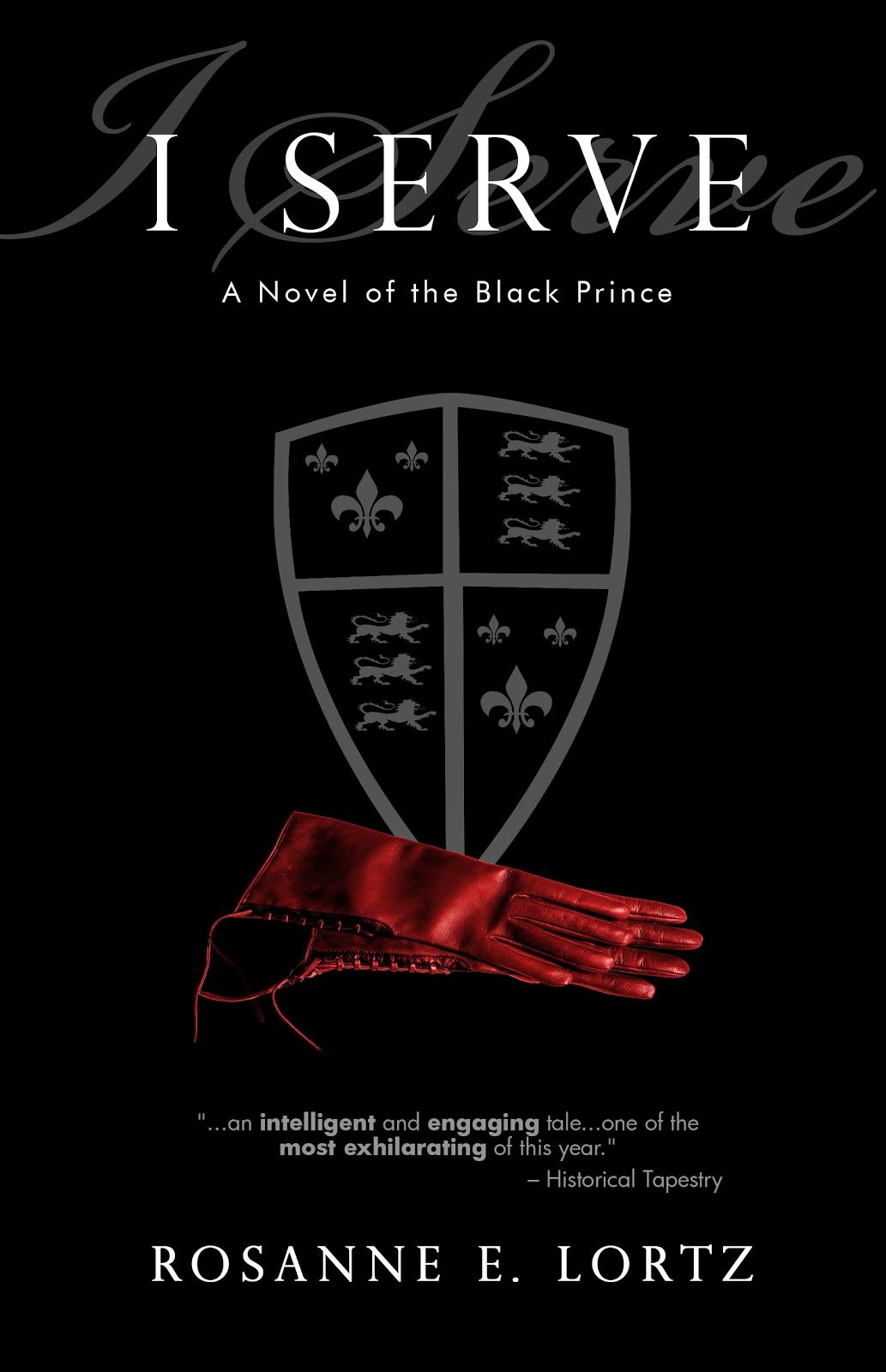

Rosanne E. Lortz is the author of two books: I Serve: A Novel of the Black Prince, a historical adventure/romance set during the Hundred Years' War, and Road from the West: Book I of the Chronicles of Tancred, the beginning of a trilogy which takes place during the First Crusade.

____

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Huizinga, Johan. The Autumn of the Middle Ages. Translated by Rodney J. Payton and Ulrich Mammitzsch. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

I rather like primary sources, but you really have to know something already to work out what is right and what is likely to be wrong and where do you go from there? This year I was teaching year 8 history and had to study the Vikings. I found snippets of primary sources - Ibn Fadlan , who describes those he met as good looking but filthy in their habits, and a later source that described them as annoyingly clean and so the Viking men were getting all the girls!

ReplyDelete