By Kim Rendfeld

| A 9th century manuscript illustration with Alcuin in the middle. |

Neither side is innocent. The Saxons burned churches and killed indiscriminately, the latter perhaps as a thanksgiving to the war god. As for the Franks, in 782, Charles issued a capitulary that among other things called for the death of anyone who didn’t convert to Christianity.

In 789, Alcuin was optimistic about the spread of Christianity and for good reason. The Saxon war leader Widukind had accepted baptism four years before, and the peace thus far held. Alcuin asked a friend how the Saxons took his preaching, and a few months later, he praised Charles for pressuring the Saxons to convert whether it was with rewards or threats.

Three years later, Charles’s wars with the Saxons had restarted. Other contemporary sources complain that the Saxons broke their oaths. The entry in the Lorsch annals invokes Proverbs and compares the Saxons’ reverting to paganism, burning churches, and killing priests “as a dog returns to its vomit.”

Alcuin took a more nuanced approached in 796. Writing to Arno, a former student and bishop of Salzburg, Alcuin advised, “And be a preacher of compassion, not an exactor of tithes … It is tithes, men say, that have destroyed the faith of the Saxons.”

| A 19th century illustration of Saxons being baptized. |

In 796, the Franks had a major victory over the Avars. With Avarian leaders killed in internecine conflict, the Franks broke into a stronghold and took its riches, probably centuries of plunder. The Avar governor, identified only as the tudun, and his companions accepted baptism.

Was Alcuin trying to prevent repeating the mistakes made with the Saxons in addition to changing the Christian mission there? Again and again that year, Alcuin pleaded for a different, gentler approach to spreading Christianity, even taking his message to King Charles. He pointed out the apostles did not exact tithes from the newly converted and said it was better to lose the wealth than the soul.

In a letter to Meginfrid the chamberlain (although the real audience is King Charles), Alcuin outlined how the process should work: teach first, then baptize, then expound on the Gospel. “And if any one of these three is lacking, the listener’s soul cannot enjoy salvation. Moreover, faith, as St. Augustine says, is a matter of will, not of compulsion. A person can be drawn to faith but cannot forced to it.”

Alcuin himself was well educated. Born around 735, he had directed the school at York for 15 years before joining Charles’s court.

“If the light and sweet burden of Christ were to be preached to the obstinate people of the Saxons with as much determination as the payment of tithes has been exacted and the force of the legal decree applied for faults of the most trifling sort imaginable, perhaps they would not be averse to their baptismal vows,” he wrote to Meginfrid, adding that missionaries should be learned men, “preachers, not predators.”

Arno was, in fact, assigned mission territory in Avaria and later appointed archbishop. Perhaps another letter to him from Alcuin is as much a warning as a lament: “It is because the wretched people of the Saxons has never had the faith in its heart that it has so often abandoned the baptismal oath.”

Public domain images via Wikimedia Commons.

Sources

Charlemagne: Translated Sources by P.D. King

“Alcuin” by James Burns, The Catholic Encyclopedia (1907). Retrieved from New Advent

"Salzburg" by Cölestin Wolfsgrüber, The Catholic Encyclopedia (1912). Retrieved from New Advent

Charlemagne by Roger Collins

Carolingian Chronicles: Royal Frankish Annals and Nithard’s Histories, translated by Bernhard Walter Scholz with Barbara Rogers

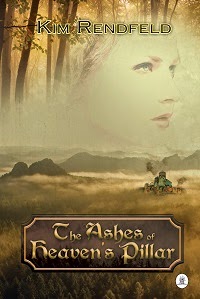

Alcuin’s letters played an important role in Kim Rendfeld’s research about eighth-century Saxony, where the story for The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar begins (August 28, 2014, Fireship Press). Kim’s latest release is a tale of the lengths a mother will go to protect her children after she’s lost everything else. To read the first chapter or find out more about Kim, visit kimrendfeld.com, her blog Outtakes of a Historical Novelist, at kimrendfeld.wordpress.com, like her on Facebook at facebook.com/authorkimrendfeld, follow her on Twitter at @kimrendfeld, or contact her at kim [at] kimrendfeld [dot] com.

Interesting post, and the fact that the Saxon's didn't write explains why they are not big historical figures in my education. You also seem to answer another question I have had for years ... why was James I and VI's christened "Charles James"? And why did he christen his second son Charles instead of James? I thought it might be because King Charles of France was one of their Godfathers, so the English name came from France. But you say Charlemagne can be shortened to Charles, a much bigger reference point. Can you fill in more about how the name derivation happened, please.

ReplyDeleteCharles comes from Carolus Magnus, or Charles the Great. He's called Charlemagne here because most readers are familiar with that name. Frankish kings recycled names, hoping to invoke heroic ancestors. So we have a lot kings named Charles and Pepin and Louis. The man we call Chalemagne was named after his grandfather, Charles the Hammer.

ReplyDeleteI'm much more familiar with English Saxons, so this post on Continental Saxons was most interesting to me. It has intrigued me enough to push the envelope on my research for a series I've recently begun.

ReplyDeleteThanks for the nudge!