By Nick Smith

Buccaneers: Pirates or Privateers? Before we can answer that question, and look at how they changed the world, we need to look at some etymology.

'Pirate' came to English via Middle French, which in turn had its origins from Greek. It originally meant something akin to brigand. An act of piracy in the 17th and 18th century was defined as an act of violence, robbery, detention or plunder upon the high seas. Illegally.

The term 'Privateer' seems English in origin from the mid-17th century, and was short for 'Private Man of War'. Privateering in the 17th and 18th century was defined as an act of violence, robbery, detention or plunder upon the high seas. Legally. Not so much of a difference, but a privateer had a piece of paper from their monarch or governor stating they were allowed to do so.

People often become hung up on the difference, but the truth of it - they were both bloodthirsty sailors in search of their fortune. Many a pirate originally had Letters of Marque (that piece of paper I mentioned) - such as the notorious Blackbeard, a successful privateer before being vilified. William Kidd was a privateer who managed to get caught up in the politics between Whigs and Tories - and was hanged for piracy.

So what's a buccaneer? Where do they come in? Time for a bit of international politics, and to explain just how they changed the world forever. The Spanish Empire's legacy to the world is massive, both linguistically and culturally. Spanish is the second most spoken language on Earth, and at some point or other the Spanish have had ownership over the majority of modern-day USA, the majority of Central and South America, most of the West Indies, half of Italy, half the Netherlands, parts of Africa and the East Indies, as well as exclusive access to China and Japan. This gave them a European monopoly on the spices, silks and porcelains of Asia, that travelled across the Pacific to the Spanish Main, joined the preciously mined gold and silver of Central and South America and sugar from the Caribbean islands; all packed aboard the great treasure galleons, then back to Europe.

In the 15th and 16th centuries Spain was the greatest world power, and with their vast wealth threatened to dominate much of Europe. You no doubt know of England's defiance by a plucky female monarch - coupled with a lucky sea storm or two - that saw us remain independent from Spanish influence.

Even though England (and later Britain) had spates of peace with Spain throughout the 17th century, Spain still had a complete stranglehold over the West Indies. The few English, Dutch and French settlements on the smaller isles were attacked aggressively in times of peace and were blocked with trade stipulations. Non-Spanish merchants attempting trade with the Spanish of the New World were deemed smugglers, and if caught by the Costa Garda were either sent to the mines for life, or garroted. For the Spanish there was but one rule: In war or not, there was no peace beyond the line of the Cape Verde islands.

The 17th century was a time of social change in England. It was a time of extremes. The English had seen the excesses of nobility, the rise of puritanism, religious persecution, including the outlawing of Christmas, and the execution of a king. It was also a time where science started to gain more traction. It left people challenging the views of authority, but also a civil war and reformation left many behind in poverty. Adventuring in the Caribbean became a way out, with many a man and woman starting their new life as indentured servants on English sugar or tobacco plantations.

Many of these indentured labourers were mistreated, beaten, forced into greater debt, and their indentured sentences increased. Runaways bonded with shipwrecked sailors, those fleeing religious persecution, and sailors jumping ship. Communities of free men (and to a lesser extent, women) sprang up around the Caribbean, with work parties of mainly English and French daring to venture into Spanish territory in search of furs, meat, redwoods and other precious timbers. The Arawak natives of Hispaniola often smoked their meat on the wooden frames of 'boucans'. The European hunters and woodcutters quickly adopted this practice - and so we end up with boucaniers, or buccaneers. Hispaniola's jungle and grassland were packed with wild cattle and pigs introduced by the Spanish a hundred odd years earlier, and left to breed. With few natural predators the animals thrived. Wild dogs also thrived, and there are references to packs attacking youths and dragging babies from their beds.

The buccaneers frequently befriended these wild canines, using them as guard dogs and for hunting companions. One extreme example was when a buccaneer hunting party lost one of their number - a youth. He was discovered several years later, naked and feral, living with a pack of wild dogs, having feasted on a diet of mainly raw pig flesh.

Many Caribbean settlements were founded in this manner, particularly on the Spanish island of Hispaniola - one of the largest islands of the West Indies. Indeed, the reason Hispaniola is split into two nations: French speaking Haiti and the Spanish speaking Dominican Republic is a direct result of invading French buccaneers from Tortuga to the North.

Spanish retaliation was often brutal, with these settlements being put to the torch. When this happened the buccaneers either defended the town with their long muskets and jungle machetes, or else melted away into the wilderness to continue trapping, barbecuing or logging until the Spanish soldiers or Costa Garda departed. Perhaps with hindsight, the Spanish would have been less hasty to attack these poor hunters and loggers if they knew what would come next.

The very survival of a buccaneer rested on his ability to use his long hunting musket - far longer than the like used by any of Europe's military forces. With small crafts, including Arawak dugout canoes, paddled in the traditional Arawak way, the buccaneers began to mobilise. To start with they sailed - or paddled - out into the windward passage: the strait between Cuba and Hispaniola. Here, with their deadly abilities and accurate muskets they would part halyards from sails, robbing their enemies of speed, and swarming their decks en masse.

Even in peacetime, did England object to their own displaced subjects robbing a rival of wealth? Not at all. In fact they encouraged it. In an attempt to undermine Spain's economy, English Naval officers such as Christopher Myngs were sent to the area. He rallied the disgruntled buccaneers to his cause, not by some notion of love to a monarch they didn't know, or an act of loyalty to their motherland. Their payment was uninhibited plunder of Spanish settlements.

Myngs' first expedition saw the sacking of Santiaga de Cuba. For his second, he had over one thousand four hundred buccaneers - they sailed for the Spanish Main itself, sacking the city of Campeche. With free reign, the buccaneers tortured individuals for the location of their hidden wealth, raped the women, hacked limbs off Spaniard's unable to pay, and pretty much set the whole place on fire.

Charles II of England was quick to condemn the attacks and recall any Naval officers advising the buccaneers, but the governors of Jamaica and other English colonies still encouraged it. And why wouldn't they? All the pilfered gold and goods passed by their hands first - and many a rich man became richer by aiding and encouraging the buccaneers. Not that they needed much encouragement of course; even with the departure of the Royal Navy, the buccaneers now knew their true calling: destruction, death, rape and plunder.

They did it very well too, and some of the most famous 'pirates' come from that period: Bartholomew Sharp, William Dampier, and of course: Henry Morgan. The latter launched many an expedition onto Cuba and the Main, each as brutal as the last. With tales of women roasted upon baking stones; others having their flesh cut away in strips; and several accounts of cord wrapped about the head, a stick inserted, and twisted. The tightened cord ultimately had the eyes popping from the skull; women and babies left to starve with no food; others strung up from buildings - all in a bid by the plundering buccaneers to find the location of hidden wealth. Unfortunately for the Spaniards, many of them had no wealth to reveal, being indentured servants themselves, and under the same trade strangulation that the rest of the West Indies felt.

These rovers became quite adept at sacking a settlement, then demanding ransom from the next settlement along - ransom for both the captives and the town itself. They would stay, drinking, eating, torturing, and whoring until they ran out of entertainment. If payment arrived from another Spanish settlement, they would frequently do as they promised - move on to another town to attack. If payment was too slow, or too little, they would take their hostages back to Jamaica and burn the offending settlement to the ground.

Modern estimates reckon the buccaneers sacked around eighteen cities, four towns, and thirty five villages. Which isn't too shoddy for unorganised rabbles of woodcutters and hunters.

So. Buccaneers: Pirates or Privateers? Who really cares. They were a bunch of bloody opportunists, badly done to by society, who finally opened up the Caribbean for the English and French. They broke down a Spanish stranglehold on trade and arguably halted Spain's economic and military dominance over Europe. They are the reason for the destabilisation of Spain's grip on the New World and why England gained a better footing in mainland America. It is unlikely that the USA would exist as an English-speaking country today if it wasn't for their bloodthirsty marauding. The buccaneers also poured gold back to England, where the wealth no doubt lingers still...

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Nick Smith is a twenty-eight year old Northumbrian in exile, currently living on a small rock in the Channel Sea where he teaches science. He has a love for all things of a nautical and historical nature.

Nick Smith is a twenty-eight year old Northumbrian in exile, currently living on a small rock in the Channel Sea where he teaches science. He has a love for all things of a nautical and historical nature.

He is the author of the gritty swashbuckling adventures ROGUES’ NEST & the newly released GENTLEMAN OF FORTUNE – both explore the reality of buccaneers and pirates at the start of the 1700s.

Find out more about his work at roguesnest.com

|

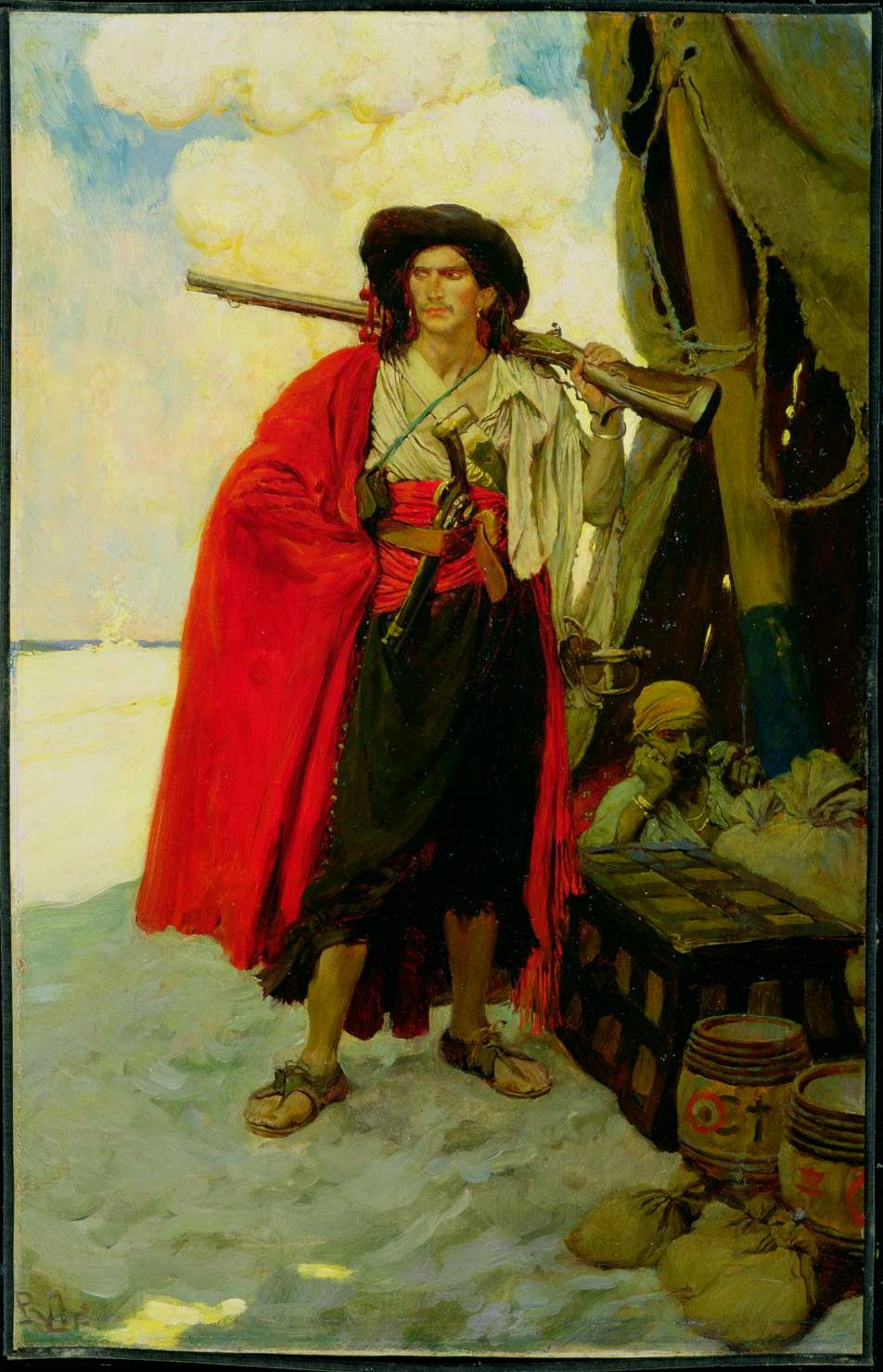

| 'Captain Scarfield' - Howard Pyle |

Buccaneers: Pirates or Privateers? Before we can answer that question, and look at how they changed the world, we need to look at some etymology.

'Pirate' came to English via Middle French, which in turn had its origins from Greek. It originally meant something akin to brigand. An act of piracy in the 17th and 18th century was defined as an act of violence, robbery, detention or plunder upon the high seas. Illegally.

The term 'Privateer' seems English in origin from the mid-17th century, and was short for 'Private Man of War'. Privateering in the 17th and 18th century was defined as an act of violence, robbery, detention or plunder upon the high seas. Legally. Not so much of a difference, but a privateer had a piece of paper from their monarch or governor stating they were allowed to do so.

People often become hung up on the difference, but the truth of it - they were both bloodthirsty sailors in search of their fortune. Many a pirate originally had Letters of Marque (that piece of paper I mentioned) - such as the notorious Blackbeard, a successful privateer before being vilified. William Kidd was a privateer who managed to get caught up in the politics between Whigs and Tories - and was hanged for piracy.

So what's a buccaneer? Where do they come in? Time for a bit of international politics, and to explain just how they changed the world forever. The Spanish Empire's legacy to the world is massive, both linguistically and culturally. Spanish is the second most spoken language on Earth, and at some point or other the Spanish have had ownership over the majority of modern-day USA, the majority of Central and South America, most of the West Indies, half of Italy, half the Netherlands, parts of Africa and the East Indies, as well as exclusive access to China and Japan. This gave them a European monopoly on the spices, silks and porcelains of Asia, that travelled across the Pacific to the Spanish Main, joined the preciously mined gold and silver of Central and South America and sugar from the Caribbean islands; all packed aboard the great treasure galleons, then back to Europe.

In the 15th and 16th centuries Spain was the greatest world power, and with their vast wealth threatened to dominate much of Europe. You no doubt know of England's defiance by a plucky female monarch - coupled with a lucky sea storm or two - that saw us remain independent from Spanish influence.

|

| The Spanish Empire - Wikipedia |

Even though England (and later Britain) had spates of peace with Spain throughout the 17th century, Spain still had a complete stranglehold over the West Indies. The few English, Dutch and French settlements on the smaller isles were attacked aggressively in times of peace and were blocked with trade stipulations. Non-Spanish merchants attempting trade with the Spanish of the New World were deemed smugglers, and if caught by the Costa Garda were either sent to the mines for life, or garroted. For the Spanish there was but one rule: In war or not, there was no peace beyond the line of the Cape Verde islands.

The 17th century was a time of social change in England. It was a time of extremes. The English had seen the excesses of nobility, the rise of puritanism, religious persecution, including the outlawing of Christmas, and the execution of a king. It was also a time where science started to gain more traction. It left people challenging the views of authority, but also a civil war and reformation left many behind in poverty. Adventuring in the Caribbean became a way out, with many a man and woman starting their new life as indentured servants on English sugar or tobacco plantations.

Many of these indentured labourers were mistreated, beaten, forced into greater debt, and their indentured sentences increased. Runaways bonded with shipwrecked sailors, those fleeing religious persecution, and sailors jumping ship. Communities of free men (and to a lesser extent, women) sprang up around the Caribbean, with work parties of mainly English and French daring to venture into Spanish territory in search of furs, meat, redwoods and other precious timbers. The Arawak natives of Hispaniola often smoked their meat on the wooden frames of 'boucans'. The European hunters and woodcutters quickly adopted this practice - and so we end up with boucaniers, or buccaneers. Hispaniola's jungle and grassland were packed with wild cattle and pigs introduced by the Spanish a hundred odd years earlier, and left to breed. With few natural predators the animals thrived. Wild dogs also thrived, and there are references to packs attacking youths and dragging babies from their beds.

The buccaneers frequently befriended these wild canines, using them as guard dogs and for hunting companions. One extreme example was when a buccaneer hunting party lost one of their number - a youth. He was discovered several years later, naked and feral, living with a pack of wild dogs, having feasted on a diet of mainly raw pig flesh.

Many Caribbean settlements were founded in this manner, particularly on the Spanish island of Hispaniola - one of the largest islands of the West Indies. Indeed, the reason Hispaniola is split into two nations: French speaking Haiti and the Spanish speaking Dominican Republic is a direct result of invading French buccaneers from Tortuga to the North.

Spanish retaliation was often brutal, with these settlements being put to the torch. When this happened the buccaneers either defended the town with their long muskets and jungle machetes, or else melted away into the wilderness to continue trapping, barbecuing or logging until the Spanish soldiers or Costa Garda departed. Perhaps with hindsight, the Spanish would have been less hasty to attack these poor hunters and loggers if they knew what would come next.

|

| 'Buccaneers of America' - A. Exquemelin |

Even in peacetime, did England object to their own displaced subjects robbing a rival of wealth? Not at all. In fact they encouraged it. In an attempt to undermine Spain's economy, English Naval officers such as Christopher Myngs were sent to the area. He rallied the disgruntled buccaneers to his cause, not by some notion of love to a monarch they didn't know, or an act of loyalty to their motherland. Their payment was uninhibited plunder of Spanish settlements.

|

| 'Exhorting Tribute from the Citizens' - Howard Pyle |

Charles II of England was quick to condemn the attacks and recall any Naval officers advising the buccaneers, but the governors of Jamaica and other English colonies still encouraged it. And why wouldn't they? All the pilfered gold and goods passed by their hands first - and many a rich man became richer by aiding and encouraging the buccaneers. Not that they needed much encouragement of course; even with the departure of the Royal Navy, the buccaneers now knew their true calling: destruction, death, rape and plunder.

They did it very well too, and some of the most famous 'pirates' come from that period: Bartholomew Sharp, William Dampier, and of course: Henry Morgan. The latter launched many an expedition onto Cuba and the Main, each as brutal as the last. With tales of women roasted upon baking stones; others having their flesh cut away in strips; and several accounts of cord wrapped about the head, a stick inserted, and twisted. The tightened cord ultimately had the eyes popping from the skull; women and babies left to starve with no food; others strung up from buildings - all in a bid by the plundering buccaneers to find the location of hidden wealth. Unfortunately for the Spaniards, many of them had no wealth to reveal, being indentured servants themselves, and under the same trade strangulation that the rest of the West Indies felt.

|

| 'Buccaneers of America' - A. Exquemelin |

These rovers became quite adept at sacking a settlement, then demanding ransom from the next settlement along - ransom for both the captives and the town itself. They would stay, drinking, eating, torturing, and whoring until they ran out of entertainment. If payment arrived from another Spanish settlement, they would frequently do as they promised - move on to another town to attack. If payment was too slow, or too little, they would take their hostages back to Jamaica and burn the offending settlement to the ground.

Modern estimates reckon the buccaneers sacked around eighteen cities, four towns, and thirty five villages. Which isn't too shoddy for unorganised rabbles of woodcutters and hunters.

So. Buccaneers: Pirates or Privateers? Who really cares. They were a bunch of bloody opportunists, badly done to by society, who finally opened up the Caribbean for the English and French. They broke down a Spanish stranglehold on trade and arguably halted Spain's economic and military dominance over Europe. They are the reason for the destabilisation of Spain's grip on the New World and why England gained a better footing in mainland America. It is unlikely that the USA would exist as an English-speaking country today if it wasn't for their bloodthirsty marauding. The buccaneers also poured gold back to England, where the wealth no doubt lingers still...

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Nick Smith is a twenty-eight year old Northumbrian in exile, currently living on a small rock in the Channel Sea where he teaches science. He has a love for all things of a nautical and historical nature.

Nick Smith is a twenty-eight year old Northumbrian in exile, currently living on a small rock in the Channel Sea where he teaches science. He has a love for all things of a nautical and historical nature.He is the author of the gritty swashbuckling adventures ROGUES’ NEST & the newly released GENTLEMAN OF FORTUNE – both explore the reality of buccaneers and pirates at the start of the 1700s.

Find out more about his work at roguesnest.com

Fascinating post. Thanks, Nick!

ReplyDeleteThank you muchly!

DeleteI enjoyed that!

ReplyDeleteThanks Rob for stopping by!

DeleteThoroughly enjoyed this post. Eager to take a look at your Novels Nick, and it sounds like you are living the exile I dream of. LOL

ReplyDeleteThanks for the kind words Marianne! Let me know what you think about the novels... ;)

Delete