by Maggi Andersen

Caroline of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (Caroline Amelia Elizabeth) was born in May 1768. Her father was the ruler of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel in modern-day Germany, and her mother, Princess Augusta, was the sister of George III. In 1794 she was engaged to George III's eldest son and heir apparent, George, Prince of Wales, although they had never met and George was already married illegally to Maria Fitzherbert.

Caroline and George were married on 8 April 1795 at the Chapel Royal, St. James's Palace, in London. At the ceremony, George was drunk. He regarded Caroline as unattractive and unhygienic and told Malmesbury he suspected that she was not a virgin when they married. He, of course, was not. His marriage to Fitzherbert violated the Royal Marriages Act 1772 and thus was not legally valid.

Shortly after their daughter Charlotte's birth George and Caroline separated. In a letter to a friend, the prince claimed that the couple only had sexual intercourse three times: twice the first night of the marriage and once the second night. He wrote, “It required no small [effort] to conquer my aversion and overcome the disgust of her person.” Caroline claimed George was so drunk that he “passed the greatest part of his bridal night under the grate, where he fell, and where I left him.”

By 1806 rumors that Caroline had taken lovers and had an illegitimate child led to an investigation into her private life. The dignitaries who led the investigation concluded that there was no foundation to the rumors, but Caroline's access to her daughter, Charlotte, was restricted.

Caroline left England to live abroad, and she was devastated when news of her daughter Charlotte’s death in childbirth reached her.

In 1818, when she was living at Pesaro, Italy, the Prince of Wales sent a team of lawyers to Milan where they interviewed potential witnesses who were subsequently brought to London for the trial.

In 1819, angry and humiliated, Caroline, who was not short on spirit, planned to return to England to challenge the Prince. When Henry Brougham, her chief legal adviser, counseled caution, she arranged to meet him at Lyons.

Caroline’s appearance in England would be most unwelcome to the Prince and his ministers. Castlereagh was instructed that she was not to be given any special attention as Princess of Wales when she travelled through France.

When Caroline arrived for the rendezvous at Lyon she found Brougham had not come. She turned back. In Leghorn (Livorno), she learned that she was Queen.

Brougham, who was playing a double game, then urged Caroline to return to England. He met her at St. Omer, and she crossed the Channel on 5 June 1820. There is some suggestion that Castlereagh wished to find a way to stop Caroline crossing the Channel, perhaps with the help of the French police, but this never eventuated.

With George III’s death in January 1820, George IV succeeded to the throne. Determined that Caroline enjoy no queenly rights and privileges, he began collecting various damaging documents that would show his minsters the kind of woman she was, which he placed in a notorious green bag, intent on using it against her in divorce proceedings. He was also determined to bar her from his coronation. He wished to get rid of her, but his ministers were anxious to avoid a divorce. They were afraid that in the process as much mud would stick to him as to her, and the monarchy itself might suffer.

Caroline arrived early in June cheered by crowds everywhere. Aware of the King’s unpopularity she made a bold bid for popular support. She was determined that she should be recognized as Queen, but the King was equally determined that she should not. No compromise was possible.

Lord Liverpool groped into the deepest recesses of the law, and the government resorted to an old parliamentary maneuver, a Bill of Pains and Penalties, the second reading of which would be tantamount to a trial and, if passed by both Houses of Parliament, this would deprive Caroline of her status as Queen and end her marriage to the King.

Her relationship with Bartolemeo Pergami, an Italian engaged initially as a courier, would come under scrutiny. Caroline had bought him an estate in Sicily which held the title Baron and appointed him her chamberlain. There was a strong rumor that they were lovers.

Caroline’s lawyers claimed Pergami was impotent. Pergami when questioned claimed frostbite had caused it on the retreat from Russia. This did not impress expert medical witnesses as proof or evidence of impotence. Pergami’s other relationships were then examined, but no proof could be found. The Abandonment of the Bill was announced to Queen Caroline in 1820.

The trial duly took place but was a minefield as they questioned Caroline’s discarded servants. As they pried into every corner of Caroline’s relationship with Pergami, it degenerated into examining filthy clothes-bags, stains on bedclothes and worse. It had an inconclusive ending. It was never claimed on Caroline’s behalf that Pergami was impotent, and it was generally agreed that she committed adultery with him and others; but it was also agreed that her treatment at the hands of the King and his ministers was reprehensible. The bill had little support and was withdrawn.

Caroline said of the bill: “Nobody cares for me in this business...this business has been more cared for as a political business than as the cause of a poor forlorn woman.” She took the dropping of the Bill as a great personal triumph to be shared with her innumerable supporters.

Caroline's last spectacular appearance was on 29 November at St. Pauls where she was cheered by an enormous mob.

Caroline was given a royal residence and an annuity of 50,000 pounds, but never gained the recognition that she craved, and she died less than a year later in August 1821.

The Prince of Pleasure and His Regency by J.B.Priestley

Private Secret. The Clandestine Activities of a Nineteenth Century Diplomat by Robert Franklin

Wikipedia Wikipedia Commons

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Maggi Andersen is author of The Spies of Mayfair Series.

Website

Amazon US

Amazon UK

|

| Queen Caroline 1820 |

Caroline of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (Caroline Amelia Elizabeth) was born in May 1768. Her father was the ruler of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel in modern-day Germany, and her mother, Princess Augusta, was the sister of George III. In 1794 she was engaged to George III's eldest son and heir apparent, George, Prince of Wales, although they had never met and George was already married illegally to Maria Fitzherbert.

Caroline and George were married on 8 April 1795 at the Chapel Royal, St. James's Palace, in London. At the ceremony, George was drunk. He regarded Caroline as unattractive and unhygienic and told Malmesbury he suspected that she was not a virgin when they married. He, of course, was not. His marriage to Fitzherbert violated the Royal Marriages Act 1772 and thus was not legally valid.

Shortly after their daughter Charlotte's birth George and Caroline separated. In a letter to a friend, the prince claimed that the couple only had sexual intercourse three times: twice the first night of the marriage and once the second night. He wrote, “It required no small [effort] to conquer my aversion and overcome the disgust of her person.” Caroline claimed George was so drunk that he “passed the greatest part of his bridal night under the grate, where he fell, and where I left him.”

By 1806 rumors that Caroline had taken lovers and had an illegitimate child led to an investigation into her private life. The dignitaries who led the investigation concluded that there was no foundation to the rumors, but Caroline's access to her daughter, Charlotte, was restricted.

Caroline left England to live abroad, and she was devastated when news of her daughter Charlotte’s death in childbirth reached her.

In 1818, when she was living at Pesaro, Italy, the Prince of Wales sent a team of lawyers to Milan where they interviewed potential witnesses who were subsequently brought to London for the trial.

In 1819, angry and humiliated, Caroline, who was not short on spirit, planned to return to England to challenge the Prince. When Henry Brougham, her chief legal adviser, counseled caution, she arranged to meet him at Lyons.

Caroline’s appearance in England would be most unwelcome to the Prince and his ministers. Castlereagh was instructed that she was not to be given any special attention as Princess of Wales when she travelled through France.

When Caroline arrived for the rendezvous at Lyon she found Brougham had not come. She turned back. In Leghorn (Livorno), she learned that she was Queen.

Brougham, who was playing a double game, then urged Caroline to return to England. He met her at St. Omer, and she crossed the Channel on 5 June 1820. There is some suggestion that Castlereagh wished to find a way to stop Caroline crossing the Channel, perhaps with the help of the French police, but this never eventuated.

With George III’s death in January 1820, George IV succeeded to the throne. Determined that Caroline enjoy no queenly rights and privileges, he began collecting various damaging documents that would show his minsters the kind of woman she was, which he placed in a notorious green bag, intent on using it against her in divorce proceedings. He was also determined to bar her from his coronation. He wished to get rid of her, but his ministers were anxious to avoid a divorce. They were afraid that in the process as much mud would stick to him as to her, and the monarchy itself might suffer.

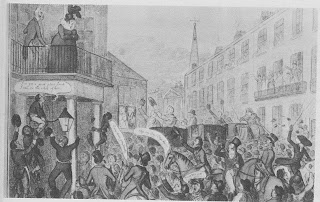

Caroline arrived early in June cheered by crowds everywhere. Aware of the King’s unpopularity she made a bold bid for popular support. She was determined that she should be recognized as Queen, but the King was equally determined that she should not. No compromise was possible.

|

| The Landing of Queen Caroline at Dover to claim her rights. |

Lord Liverpool groped into the deepest recesses of the law, and the government resorted to an old parliamentary maneuver, a Bill of Pains and Penalties, the second reading of which would be tantamount to a trial and, if passed by both Houses of Parliament, this would deprive Caroline of her status as Queen and end her marriage to the King.

Her relationship with Bartolemeo Pergami, an Italian engaged initially as a courier, would come under scrutiny. Caroline had bought him an estate in Sicily which held the title Baron and appointed him her chamberlain. There was a strong rumor that they were lovers.

Caroline’s lawyers claimed Pergami was impotent. Pergami when questioned claimed frostbite had caused it on the retreat from Russia. This did not impress expert medical witnesses as proof or evidence of impotence. Pergami’s other relationships were then examined, but no proof could be found. The Abandonment of the Bill was announced to Queen Caroline in 1820.

|

| The Trial of Queen Caroline 1820 |

The trial duly took place but was a minefield as they questioned Caroline’s discarded servants. As they pried into every corner of Caroline’s relationship with Pergami, it degenerated into examining filthy clothes-bags, stains on bedclothes and worse. It had an inconclusive ending. It was never claimed on Caroline’s behalf that Pergami was impotent, and it was generally agreed that she committed adultery with him and others; but it was also agreed that her treatment at the hands of the King and his ministers was reprehensible. The bill had little support and was withdrawn.

|

| The Abandonment of the Bill presented to Queen Caroline |

|

| The Queen returning from the House of Lords, 1821. |

Caroline said of the bill: “Nobody cares for me in this business...this business has been more cared for as a political business than as the cause of a poor forlorn woman.” She took the dropping of the Bill as a great personal triumph to be shared with her innumerable supporters.

|

| Caroline’s arrival at Brandenburgh House of the Watermen. |

|

| A Late arrival at Mother Wood’s 1820 |

Caroline's last spectacular appearance was on 29 November at St. Pauls where she was cheered by an enormous mob.

Caroline was given a royal residence and an annuity of 50,000 pounds, but never gained the recognition that she craved, and she died less than a year later in August 1821.

The Prince of Pleasure and His Regency by J.B.Priestley

Private Secret. The Clandestine Activities of a Nineteenth Century Diplomat by Robert Franklin

Wikipedia Wikipedia Commons

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Maggi Andersen is author of The Spies of Mayfair Series.

Website

Amazon US

Amazon UK

Forced into a marriage with Prinny would entice any woman to look elsewhere for love. What a unhappy life this woman had.

ReplyDeleteI do feel sorry for her. The prince could have handled it better from the beginning, but that wasn't his style.

ReplyDeleteI agree Darlene, it would have devastated any woman, but I think she made the best of it! :)

ReplyDeleteDiane, the prince was a bit of a victim in this too, being unable to legally marry the woman he loved, but yes, he acted cruelly.

ReplyDelete