By Rosanne E. Lortz

Henry V is best remembered as the Lancaster king of England who fought the French at the Battle of Agincourt, and, against overwhelming odds, carried the field and claimed the crown of France. He is not remembered for being a musical composer during the glorious era of fifteenth century English choral music.

Yet although the story of longbows has won out over the story of the lute, it is certain that music was an important aspect of Henry’s life. Thomas Elmham, a contemporary chronicler who would become one of Henry’s chaplains, described Henry’s early life thus:

The prince’s predilection for playing musical instruments lent itself to the penning of musical compositions as well. In the Old Hall Manuscript, the best extant source for late Medieval English music (now located at the British Library), there are two compositions attributed to “Roy Henry”—which is translated “King Henry.” Most musicologists accept that the king referred to is in fact Henry V, although some wish to attribute the pieces to his father Henry IV.

Richard Taruskin, in the Oxford History of Western Music, offers a suggestion that could harmonize the two camps of thought about the Old Hall Manuscript:

The first piece is a Sanctus, a standard piece from the medieval mass with the words:

The second Roy Henry piece is a Gloria, another standard piece from the medieval mass, which begins with the words spoken by the angels, “Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace to men of goodwill.” The parts for this one are written out separately, “choirbook fashion,” with the predominant top voice being supported by the others “in an advanced ars nova cantilena style.” (You can hear a clip from the Gloria here.)

Putting musical terminology aside, suffice it to say that both Roy Henry pieces are up to par with the rest of the works in the collection. Henry was no slouch on the battlefield, and he was, apparently, no slouch at writing music either.

Interestingly enough, the early fifteenth century during which Henry lived marked a golden age for English music. Historian Elizabeth Hallam writes:

Elizabeth Hallam writes:

_________________

Rosanne E. Lortz is the author of two books: I Serve: A Novel of the Black Prince, a historical adventure/romance set during the Hundred Years' War, and Road from the West: Book I of the Chronicles of Tancred, the beginning of a trilogy which takes place during the First Crusade.

You can learn more about Rosanne's books at her Official Author Website where she also blogs about writing, mothering, and things historical.

_________________

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Church, Alfred John. Henry V. London: MacMillan and Co., 1891.

Hallam, Elizabeth, ed. The Wars of the Roses: From Richard II to the Fall of Richard III at Bosworth Field—Seen through the Eyes of Their Contemporaries. New York: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1988.

Taruskin, Richard. Oxford History of Western Music: Music from the Earliest Notations to the Sixteenth Century. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

WESTMORELAND:

O that we now had here

But one ten thousand of those men in England

That do no work to-day!

KING HENRY V:

What's he that wishes so?

My cousin Westmoreland? No, my fair cousin;

If we are mark'd to die, we are enow

To do our country loss; and if to live,

The fewer men, the greater share of honour….

Henry V is best remembered as the Lancaster king of England who fought the French at the Battle of Agincourt, and, against overwhelming odds, carried the field and claimed the crown of France. He is not remembered for being a musical composer during the glorious era of fifteenth century English choral music.

Yet although the story of longbows has won out over the story of the lute, it is certain that music was an important aspect of Henry’s life. Thomas Elmham, a contemporary chronicler who would become one of Henry’s chaplains, described Henry’s early life thus:

He was in the days of his youth a diligent follower of idle practices, much given to instruments of music, and one who, loosing the reins of modesty, though zealously serving Mars, was yet fired with the torches of Venus herself, and, in the intervals of his brave deeds as a soldier, wont to occupy himself with the other extravagances that attend the days of undisciplined youth.Here we see that along with fighting and wenching, the young Henry numbered playing musical instruments among his other “extravagances.” This idea is confirmed by Tito Livio Frulovisi, an Italian biographer later employed by Henry’s brother, who wrote that the young Henry “delighted in song and musical instruments.”

The prince’s predilection for playing musical instruments lent itself to the penning of musical compositions as well. In the Old Hall Manuscript, the best extant source for late Medieval English music (now located at the British Library), there are two compositions attributed to “Roy Henry”—which is translated “King Henry.” Most musicologists accept that the king referred to is in fact Henry V, although some wish to attribute the pieces to his father Henry IV.

Richard Taruskin, in the Oxford History of Western Music, offers a suggestion that could harmonize the two camps of thought about the Old Hall Manuscript:

Henry IV and Henry V…both reigned during the period of its compiling. Opinions still differ as to which of them may have composed the two pieces attributed to Roy Henry…but as the two pieces differ radically in style it is not impossible that each of the two kings may have written one.Even with the remote possibility that Henry IV may have written one of the pieces, it is almost certain that the other was composed by Henry V.

The first piece is a Sanctus, a standard piece from the medieval mass with the words:

Sanctus, Sanctus, Sanctus

Dominus Deus Sabaoth.

Pleni sunt caeli et terra gloria tua.

Hosanna in excelsis.

Benedictus qui venit in nomine Domini.

Hosanna in excelsis.

Holy, Holy, HolyTaruskin describes Roy Henry’s Sanctus as “smoothly and skillfully written” with full, rich chords. “It can be taken as representative of 'normal' English style…just before that style became widely known and momentously influential on the continent.”

Lord God of Hosts.

Heaven and earth are full of your glory.

Hosanna in the highest.

Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord

Hosanna in the highest.

|

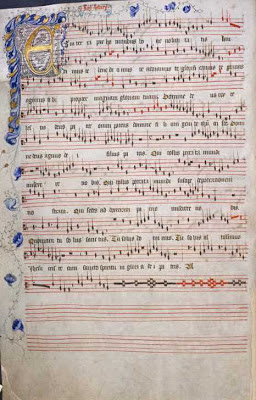

| Roy Henry's "Gloria" in the Old Hall Manuscript |

The second Roy Henry piece is a Gloria, another standard piece from the medieval mass, which begins with the words spoken by the angels, “Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace to men of goodwill.” The parts for this one are written out separately, “choirbook fashion,” with the predominant top voice being supported by the others “in an advanced ars nova cantilena style.” (You can hear a clip from the Gloria here.)

Putting musical terminology aside, suffice it to say that both Roy Henry pieces are up to par with the rest of the works in the collection. Henry was no slouch on the battlefield, and he was, apparently, no slouch at writing music either.

Interestingly enough, the early fifteenth century during which Henry lived marked a golden age for English music. Historian Elizabeth Hallam writes:

The English had a reputation as musicians. On its way to the Council of Constance (1414-1418), the delegation led by the bishops of Norwich and Lichfield delighted the congregation in Cologne Cathedral with singing, ‘better than any had heard these thirty years’.The magnificent sounds of English choirs taking their show on the road soon began to impact musicians and composers on the continent. French and Italian composers started using the full, harmonious chords of English music, giving up the stark parallelism of an earlier musical tradition.

Elizabeth Hallam writes:

The early 15th century was the only time in history that English musicians helped shape the direction of European music. Henry V’s victory at Agincourt, celebrated in the ‘Agincourt Carol’, meant that a generation of English nobles and churchmen were regular visitors to northern France—and with them came their music.Although Henry V will probably always be most remembered as the “warlike Harry” of Shakespeare’s immortal play, with “famine, sword and fire...leash'd in like hounds" at his heels, it rounds out our picture of the man to remember the “musical Harry” as well. And ironically enough, it was his success with the sword that transported the voices of English choirs and the scribblings of English composers across the Channel—with such great success that “not until the 20th century did English music again win such prestige.”

_________________

Rosanne E. Lortz is the author of two books: I Serve: A Novel of the Black Prince, a historical adventure/romance set during the Hundred Years' War, and Road from the West: Book I of the Chronicles of Tancred, the beginning of a trilogy which takes place during the First Crusade.

You can learn more about Rosanne's books at her Official Author Website where she also blogs about writing, mothering, and things historical.

_________________

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Church, Alfred John. Henry V. London: MacMillan and Co., 1891.

Hallam, Elizabeth, ed. The Wars of the Roses: From Richard II to the Fall of Richard III at Bosworth Field—Seen through the Eyes of Their Contemporaries. New York: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1988.

Taruskin, Richard. Oxford History of Western Music: Music from the Earliest Notations to the Sixteenth Century. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

I so appreciated this post, Lorraine (and actually hearing a snippet of Henry's music was an added and unexpected treat). We need to constantly remind ourselves that every well-rounded aristocrat, man or woman, of the period could sing, dance, play the lute or viol or virginal or other demanding instrument, compose poetry,speak a language other than their own, and on and on. Abilities that today we would ascribe to a veritable "Renaissance Man" or Woman were, even before the actual Renaissance, expected of a well-educated and well-rounded princely individual. Thanks for reminding us of this, and introducing me to Harry's music.

ReplyDeleteThanks for the comment, Octavia! It's very true that we see these sorts of talents in a lot of other monarchs (Henry VIII's music and Elizabeth I's poetry come to mind), but it surprised me, for some reason, to see it in Henry V, and that's why I wrote the blog. :-)

Delete