The Yorkists were a hard-headed lot, basing their right to rule on bloodline. When their last king, Richard Plantagenet, was slain at the Battle of Bosworth on August 22, 1485, his devastated Yorkist supporters--as well as the rest of the country--waited to hear what claim to the throne the victor, Henry Tudor, earl of Richmond, would put forth.

It was a delicate question.

|

| Henry VII |

We can imagine there was a certain level of suspense as the country waited. Most assumed that the newly declared Henry VII would swiftly marry Elizabeth of York, oldest living child of the dead Edward IV, and attach his weak claim to her greater one. But he did not marry her right away--it was important to him to claim the right to rule on his own.

When he invaded England with French-financed troops, Tudor had marched through his family stronghold of Wales, gaining support and men, under the banner of the red dragon: the battle standard of King Arthur and other Celtic leaders. Now it was announced that Henry Tudor was descended from Arthur himself through Cadwaladr and the Welsh chieftains who were ancestors of Owen Tudor. Genealogists had confirmed this, the skeptical court was informed. Henry's ascension was the fulfillment of prophecy.

Despite such grandiose claims, Henry married Elizabeth of York. But he did not drop the Arthur business. Far from it: He insisted that his first child be born in Winchester, sometimes identified as Camelot in legend. And when that baby boy was born, he was named...Arthur.

|

| Le Morte D'Arthur |

Henry VII would not be the first ruler to seize on the romance of Camelot to bolster his regime. But the direct connection of his legal claim to rule to a work of mythic entertainment is bold indeed--if not bizarre. It was as if, in 1977, the year Star Wars hit theaters, a president appeared who announced himself descended from Luke Skywalker.

But there were darker elements to this claim to Camelot. In legitimizing a mystical prophecy, Henry VII was unleashing a certain kind of power that would reach across the entire 16th century and into the 17th, bedeviling his great-great-grandson. Rebels against various Tudor regimes would repeatedly use their own prophecies to rally support. They effectively co-opted Henry VII's modus operandi, down to the symbolic banners. A frustrated Henry VIII sought to ban prophecy from his kingdom after he was nearly engulfed by seers, witches, and necromancers spouting predictions, many of them derived, allegedly, from Merlin and yet coded and obscure, open to many interpretations.

|

| The Pilgrimage of Grace, and its many banners |

Again and again, strange prophecies emerged in times of political distress in the Tudor era. After a young nobleman named Anthony Babington was arrested for a treasonous conspiracy to murder Elizabeth I and replace her with Mary Queen of Scots, a book of Merlin prophecies was found in Babington's London home.

|

| John Dee and Edward Kelley |

It is with James VI that the brew of prophecy and the occult overflows. James was a Stuart king of Scotland, but part Tudor too, descended through both his parents--Mary Queen of Scots and Henry, Lord Darnley--from Margaret Tudor, the oldest daughter of Henry VII.

Scotland was already a place uneasy with such fears before James VI was born. The Act of 1563 forbade anyone to use witchcraft, sorcery or necromancy or to claim any of its powers, the penalty for both witch and client being death.

|

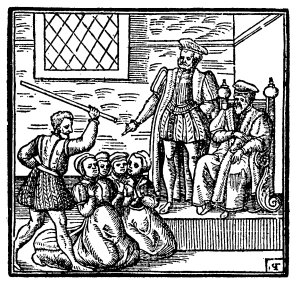

| James VI overseeing witch trials |

As a young man, James VI became convinced that witches were trying to kill him, specifically creating storms to drown him and his bride, Anne of Denmark, as he tried to bring her to Scotland. Afterward he oversaw witch trials, ordering torture of suspects, that led to a flurry of executions. In 1597 James personally wrote an 80-page book called Daemonologie expounding on his views on the dangers of sorcery and magic. Shakespeare drew from it when writing Macbeth, considered by many a tribute to King James, with its three witches spouting eerie prophecy that would change men's destinies.

His entire life, James VI was tormented by fears of a violent death. In the end he died in his bed, the king of England and Scotland. But fears of prophecy and of witchcraft, which he'd done so much to whip into a frenzy, did not die with him; instead, the frenzy led to the deaths of more English victims, and traveled to America with the Puritan settlers, before finally loosening their hold.

-------------------------------------------------------------

Nancy Bilyeau is the author of the historical-mystery trilogy The Crown, The Chalice and The Tapestry. To learn more, go to www.nancybilyeau.com.

Oh, that's very interesting!

ReplyDeleteThank you, Farida

ReplyDeleteSpin-doctoring in history. Fascinating stuff! Thanks!

ReplyDeleteCan't wait to read it Nancy.. so looking forward to a great "read".

ReplyDeleteOne historical fact that is rather ironic is that the Yorskists themselves were descendants the the female line from Edward III- and their 'claim' to the throne was through the female line- in fact twice over. Through Phillipa, daughter to Lionel of Antwerp, and Anne Mortimer, mother of Richard Duke of York.

ReplyDeleteIn this sense, the Lancastrians had a stronger claim- they were direct descendants in the male line- but the Yorkists of course killed them off- and did a pretty good job of killing each other off too....

I'll say this for Henry VII, he was canny! Early spin-doctoring is right! I saw a program while on holiday in the UK last year about the Tudors as early brand-builders, which had never really occurred to me before that show. But it was true - they used all the communication tools at their disposal - heraldic devices, genealogy and the story-telling, mythologizing and symbolic banners Nancy mentions.

ReplyDeleteGreat post Nancy.

Can't WAIT to read THE CHALICE!!

ReplyDelete