by guest author Margaret Skea

Most of us only get married once (to the

same person).

Things used to be different – for royalty

at least…

Some of us may have written a poem to our

beloved (not guilty).

That’s something that hasn’t changed.

A poem written by

James VI to Anne of Denmark ~ 1589

What mortal man may

live but hart*

As I do now, suche is

my cace

For now the whole is

from the part

Devided eache in divers place.

The seas are now the

barr

Which makes us

distance farr

That we may soone win

narr**

God graunte us grace…

* without love

** near

Born in 1566, James became king at the age of one, following the forced abdication of his mother Mary Queen of Scots in 1567.

In 1589, now 23, negotiations for a suitable

marriage, which had been a matter of primary concern to court and country alike

since his 16th birthday, were finally concluded.

His choice, Anne of Denmark, was one that

pleased himself – she was young and handsome. It pleased his subjects – reinforcing the

already important trade links with Denmark. And, he said, it pleased God - who had

‘moved his heart in the way that was meetest’.

His choice, Anne of Denmark, was one that

pleased himself – she was young and handsome. It pleased his subjects – reinforcing the

already important trade links with Denmark. And, he said, it pleased God - who had

‘moved his heart in the way that was meetest’.

Whether

James’ understanding of God’s will was influenced more by the fact that Anne

was eight years younger than himself, while the other candidate, Catherine of

Navarre, was eight years older and reputedly looking her age, than by the

earnest prayer he claimed, is a moot point.

Whatever, the contract was made and his chosen proxy, George Keith,

Earl Marishchal, was charged, not only with taking James’ place at the marriage

ceremony, but also with the task of bringing the new queen home.

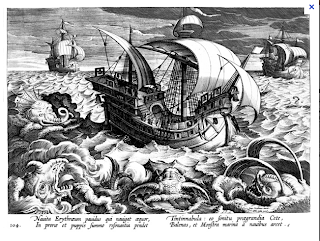

On the 1st September 1589 a

small fleet left Denmark heading for Scotland.

It was to be an ill-fated

voyage. Storms battered the ships; the queen’s life was endangered by cannons which

broke loose from the their mountings; and when prayers failed to calm the seas, Peter

Munk, the Danish Admiral, concluding that the storms were the work of witches,

sought safe haven in Norway.

It was to be an ill-fated

voyage. Storms battered the ships; the queen’s life was endangered by cannons which

broke loose from the their mountings; and when prayers failed to calm the seas, Peter

Munk, the Danish Admiral, concluding that the storms were the work of witches,

sought safe haven in Norway.

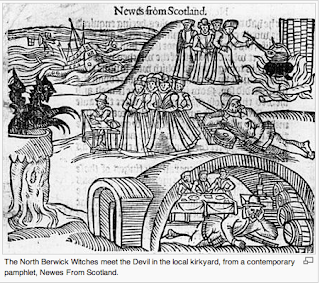

Munk’s belief that witches played a part in

the storms that threatened the ships, was one which James was ready to accept

and witch trials followed in both countries, including the infamous North

Berwick trials of 1590.

Unwilling to wait until the following

spring, James resolved to send ships from Scotland to bring Anne home. But when

his Lord Admiral, the Earl of Bothwell, told him how much such a venture would

cost, he quickly changed his mind. In fairness, though James had a reputation of being canny, especially where money was

concerned; he probably couldn’t afford it.

Unwilling to wait until the following

spring, James resolved to send ships from Scotland to bring Anne home. But when

his Lord Admiral, the Earl of Bothwell, told him how much such a venture would

cost, he quickly changed his mind. In fairness, though James had a reputation of being canny, especially where money was

concerned; he probably couldn’t afford it.

Enter Maitland, Lord Chancellor of Scotland,

who volunteered to send ships at his own expense. An offer that James was quick

to accept.

James then made what would be the most

impulsive and foolhardy gesture of his life, disregarding the increased dangers

of winter seas and deciding to accompany the fleet to Norway. Knowing it would not please his council

however, he took care both to ensure that word of his intention did not leak

out until it was too late for them to stop him, and to leave detailed

instructions for the governance of the

country in his absence. He was to be away for more than six months.

Fortunately for James, the journey, which Anne’s

ships had struggled to make for almost a month, took just 6 days, and he arrived

in Norway at the end of October.

There followed wedding No.2 in Oslo,

conducted in French by a Scots minister who had accompanied James, and finally,

in January 1590, for the benefit of the Danish royal family, wedding No 3 at

the castle of Kronborg in Denmark.

There followed wedding No.2 in Oslo,

conducted in French by a Scots minister who had accompanied James, and finally,

in January 1590, for the benefit of the Danish royal family, wedding No 3 at

the castle of Kronborg in Denmark.

Thoroughly

married, by both Scots and Lutheran rites, the royal couple and their entourage

caroused the winter away in Denmark, finally leaving on the 21st

April 1590. They arrived at the port of

Leith, just outside Edinburgh, on 1st May 1590, to a tumultuous

welcome from a populace eager for a young and healthy king and queen.

It was a marriage that lasted thirty years

until Anne’s death in 1619, and though the initial happiness did not last, they

had eight children – three sons and five daughters. Their firstborn, Henry, having died in 1612,

it was their second son Charles who succeeded James; the marriage of their only

surviving daughter, Elizabeth, to Frederic V, Elector Palatine and King of

Bohemia eventually leading to the Hanovarian succession to the British throne.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Margaret Skea grew up in

Ulster at the height of the 'Troubles', but now lives with her husband in the

Scottish Borders.

Her debut novel, Turn of the Tide - the Historical Fiction Winner in the 2011 Harper Collins / Alan Titchmarsh People's Novelist Competition – is set in 16thc Scotland and is the story of a fictional family trapped in a real-life vendetta between warring clans. It was published by Capercaillie Books in November 2012.

Her debut novel, Turn of the Tide - the Historical Fiction Winner in the 2011 Harper Collins / Alan Titchmarsh People's Novelist Competition – is set in 16thc Scotland and is the story of a fictional family trapped in a real-life vendetta between warring clans. It was published by Capercaillie Books in November 2012.

An Hawthornden Fellow and award winning short

story writer - other recent credits include, Overall Winner Neil Gunn 2011,

Chrysalis Prize 2010, and Winchester Short Story Prize 2009. Shortlisted in the

Mslexia Short Story Competition 2012 and long-listed for the Matthew Pritchard

Award, Fish Short Story and Fish One Page Prize, she has been published in a

range of magazines and anthologies in Britain and the USA.

There is an excellent book Scotland's Last Royal Wedding that treats the issues surrounding the marriage in a very entertaining and thorough account, including how James left Holyrood to embark from Leith under cover of darkness. The final chapter is telling "And they did not live happily ever after." It is by historian David Stevenson and includes the Danish account of the event. It reads like a novel, for anyone interested in looking a little deeper into this topic that Margaret Shea presents.

ReplyDeleteFascinating! I didn't know the story of James and Anne's marriage.

ReplyDeleteThanks for sharing!