By Donna Scott

Almost everyone has heard of Jack the Ripper, the villain who wandered the streets of London in 1888, killing prostitutes in the dead of night. Few people are aware, however, that he had a predecessor, a sexual miscreant who terrorized those same streets exactly one hundred years earlier. Although he did not have a predilection for prostitutes, his weapon of choice was the same. That man was known as The London Monster.

His reign of terror lasted from March 1788 to June 1790. Within that timeframe, he attacked approximately 56 women. This number remains in question, however, because many believe some of his attacks were not reported and others were fabricated. But more on that later.

|

| The Monster going to take his Afternoons Luncheon (etching by James Gillray 1790) The victim is wearing a copper cuirass over her bottom to protect her from his attack |

In 1790, London was a highly sexualized city. There were over 10,000 prostitutes, women of all ages from various backgrounds, many of whom were wives trying to earn an extra shilling or two to help with household expenses. Brothels and molly houses existed in every part of town from Pall Mall to Charing Cross and Drury Lane and, of course, in Covent Garden. Erotic novels, vulgar songs, and pornographic prints abounded. Members of all classes frequented live shows with both male and female nude dancers. Naturally, the sexual malignance of the city brought with it crime and corruption. In essence, London was rife with whores, vagabonds, and thieves and, therefore, was the perfect place for the monster to thrive.

|

| The Monster Cutting a Lady (print by Isaac Cruikshanks 1790) He is seen herewith a blade in his hands and blades attached to his knees, attacking a lady |

Over time, the monster’s modus operandi evolved. As the story goes, he approached only beautiful women with a comment, many times of a sexual nature, which was met with reproach and disgust. His actual words were said to be so indecent that the women who reported his attacks wouldn’t repeat them. In the testimony of two sisters—Anne and Sarah Porter—they accused him of using “very gross,” “dreadful,” and “abusive” language so, out of decency, much of what he said was never disclosed in the court transcripts. He would insult, abuse, and cut his victims with a knife, sometimes slicing through their gowns and into their flesh. Some claimed he had a sharp object connected to his hand or knee and would use it strategically in the assault. Most of the time, the point of impact was in the hip, thigh, or buttocks, some suspecting those areas were targeted with sexual intent. It wasn’t until April of 1790, that one of his victims was sliced through her nose when he asked her to smell a nosegay with a sharp object hidden inside. All of these varied attacks stirred up an hysteria that led women to wear copper cuirasses underneath their skirts that covered their backsides, should the monster attack.

|

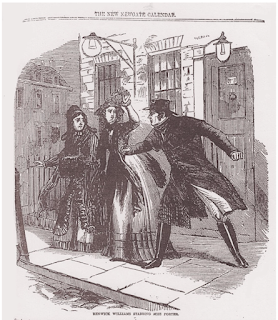

| The London Monster stabbing Miss Anne Porter (aged 21), her sister Sarah (aged 19), beside her. (Drawing from the Newgate Calendar, 1790) |

Men everywhere started to worry over their wives, sisters, and daughters, demanding that the villain be caught. As a result, John Angerstein, a wealthy insurance broker and art collector, offered a reward of 100 pounds—50 pounds for the capture and arrest of the monster and the remaining 50 pounds once he was convicted. This brought about a slew of vigilante monster-hunters roaming the streets at night, accusing and restraining innocent men throughout London. Angerstein pasted posters all over the city with various descriptions of the monster, all obtained from the victims and witnesses, and none of which quite matched. He eventually acknowledged the frenzy he created over finding the monster, ironically stating that “it was not safe for a gentleman to walk the streets, unless under the protection of a lady”.

Because of this hysteria, historians believe many of the attacks may have been fabricated. As the monster was known to attack only beautiful women, several women were suspected of slashing their own gowns and mildly injuring themselves to gain social celebrity. Essentially, it became a statement of one’s great beauty and, thus, an “honour” to have been selected by the man. These victims often reclined in their parlours, inviting curious visitors to take a peek at the gash or scratch where blade met flesh. During the height of the hysteria, the reports were numerous.

On June 13th 1790, a twenty-three-year-old unemployed, artificial flower maker named Rhynwick Williams was arrested as the London Monster. A day later, he was examined by the justices at the Bow Street public offices. The Porter sisters were the first to give evidence against him, identifying him as the same man who used coarse language to offer indecent proposals that eventually resulted in an assault. He was tried at the Old Bailey, and although he had at least seventeen character witnesses testifying on his behalf and several victims agreeing that he was not the man who attacked them, he was pronounced guilty by a unanimous jury and sent to Newgate.

|

| Rhynwick Williams, 1790 |

If not for the support of the Irish poet and conversationalist Theophilus Swift, who came forward to argue his innocence, Williams may have rot in prison. His efforts resulted in Williams being granted a second trial six months later. Swift maintained that because Williams was poor and of Welsh descent, he was easy to use as a scapegoat to stop the hysteria. Additionally, Swift maintained that Williams’s young and inexperienced solicitor did a horrible job defending him, his incompetence actually making the case for the prosecution. He also discredited the victims—attacking their character—and believed the Porter sisters and the fishmonger, John Coleman, conspired to declare Williams as the monster in order to claim the 100-pound award. He argued the contradictions in their testimonies also highlighted their unreliability. But all of Swift’s efforts were to no avail. Rhynwick Williams was once again found guilty and imprisoned in Newgate for 6 years. Upon his release, he was fined 200 pounds plus two sureties of 100 pounds each.

In time, the people of London quickly forgot about the monster and his depraved crimes. Many believed Williams to be innocent, yet his fate was already sealed. What is unanimously agreed upon is that the London Monster was a man with perverse sexual desires and a vulgar tongue who—although he never seriously injured anyone, and no one died from his attacks—posed a grave threat to the stability of the city and general welfare of its people.

Reference:

The London Monster: A Sanguinary Tale by Jan Bondeson. De Capo Press, 2001.

~~~~~~~~~~

Donna Scott is an award-winning author of 17th and 18th century historical fiction. Before embarking on a writing career, she spent her time in the world of academia. She earned her BA in English from the University of Miami and her MS and EdD (ABD) from Florida International University. She has two sons and lives in sunny South Florida with her husband. Her first novel, Shame the Devil, received the first place Chaucer Award for historical fiction and a Best Book designation from Chanticleer International Book Reviews. Her newest novel, The London Monster, will be released in January 2021.