by Lauren Gilbert

It’s officially autumn (even though the temperatures do not reflect it where I live), and my menu planning is making a seasonal shift. As temperatures cool and winter approaches, a richer and more sustaining menu appeals. Soup is a favourite of mine for this time of year. An ancient dish, I suspect it evolved as soon as man figured out how to put edible things in a pot of water over heat. Soup is featured in virtually all culinary traditions and, of course, is a significant part of food history in Great Britain. As a history enthusiast, I enjoy reading details of normal life, including food, whether I’m reading fiction or non-fiction, as it gives an immediacy and life to the material.

Soup also had a medicinal function. Lady Elinor Fettiplace, during the Elizabethan era, put together a household book which included a recipe for almond soup designed for “a weake Back” in her recipes for October. For this soup, a rack of mutton and a chicken were boiled in water with raisins, prunes, and the roots and leaves of ditch fern until the meat was tender. The meat was removed and the broth strained. (Additional broth should be crushed out of the meat.) The broth was then thickened with ground almonds. The recommended dosage was 12 spoonfuls in the morning (fasting, i.e. before eating anything), and 12 spoonfuls before dinner.

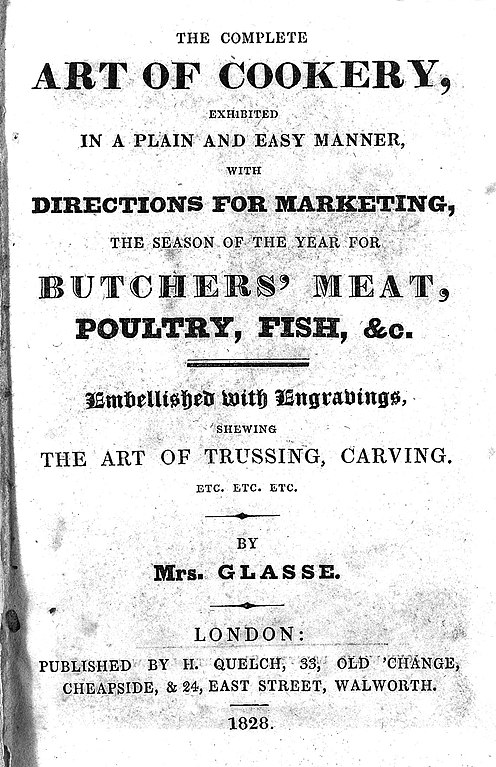

There were also soups designed for particular religious periods. Hannah Glasse’s The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy included a section of a Variety of Dishes for Lent, which included eel soup. This recipe harked back to the medieval recipes as it was served over toasted bread. For every pound of eels used, the cook used a quart of water, a crust of bread, 2 or 3 blades of mace, pepper, an onion and a bundle of sweet herbs. (One pound of eels made a pint of soup, so the cook could control the quantity accordingly.) The pot was covered tightly and boiled until half the liquid was gone. The broth was then strained. Bread was toasted, cut into small pieces and placed in a dish; the broth was then poured over it.

Soup recipes evolved over time as new ingredients became available and tastes changed. A classic example of this was Mulligatawny Soup. This soup was a chicken soup flavoured with curry. Rea Tannahill in Food in History indicated this soup appeared in England in the 18th century. British trade in India had been established since the 17th century and curry became a popular seasoning during the Georgian era. By the Victorian era, this soup was very popular. The edition of Mrs. Rundell’s A New System of Domestic Cookery mentioned previously has 4 recipes. The word “mulligatawny” (also spelled Multaanee and Malagatanee) was a corruption of the Tamil for pepper water. (The Tamil are an ethic group found in India and Sri Lanka.) The basic recipe called for onions and shallots, 2 chickens (or rabbits) pepper, butter, curry powder and turmeric, 2 quarts of strong broth, lemon juice and, if desired, a little curry powder to make it hotter. Keep in mind that curry powder was a spice mix made at home, to personal taste. (See English Historical Fiction Authors blog HERE.) One variation included cloves, and some garlic; another was made with veal, and the fourth included peas. This was a good way to use up leftover meat or vegetables. Subsequent versions included chopped apples. Cream could also be added; coconut milk may have been included. This soup is also still popular today.

Over the centuries, soup has been a common thread in culinary history. As we look back at some of the older recipes, the variety of seasonings and ingredients that are used today may seem surprising. We may not combine ingredients in exactly the same way, but it is easy to imagine how some of these soups may taste and the pleasure felt by the diners as they enjoyed them, whether elegantly spooning turtle soup at a formal dinner or enjoying the warmth of mulligatawny soup on a cold fall evening.

Sources include:

Dickson Wright, Clarissa. A History of English Food. 2011: Random House Books, London.

Glasse, The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy. A new Edition, with modern Improvements. Introduction by Karen Hess. 1805: Cottom & Stewart, Alexandria, VA. (Facsimile by Applewood Books, Bedford, MA)

Rundell, Maria Eliza Kettelby. A New System of Domestic Cookery: Founded Upon Principles of Economy and Adapted to the Use of Private Families. From the Sixty-Seventh London Edition. 1844: Carey and Hart, Philadelphia, PA. (Nabu Public Domain Reprint)

Smith, Eliza. The Compleat Housewife. 16th edition, with Additions. 1858: London. (Reprint edition published 1944: Studio Editions Ltd., London)

Spurling, Hilary. Elinor Fettiplace's Receipt Book. 1986: Penguiin Books Ltd. Hammmondsworth, England.

Tannahill, Reay. Food in History. 1988: Three Rivers Press, New York, NY.

Websites:

THE FORME OF CURY. HERE

History.com. “A Spot of Curry: Anglo-Indian Cuisine” by Stephanie Butler, April 26, 2013. HERE

GoogleBooks.com. Rumble, Victoria R. SOUP THROUGH THE AGES: A Culinary History with Period Recipes. 2009: McFarland & Company, Ind. Jefferson, NC and London. HERE

All illustrations from Wikimedia Commons Images, except for the cover of Elinor Fettiplace's Receipt Book, which is a scan of my personal copy.

About the author:

Lauren Gilbert holds a BA in English and is a long-time member of JASNA. She lives in Florida with her husband, and is the author of Heyerwood; a Novel. Another book, A Rational Attachment, is in process and will be coming soon. Please visit her website HERE for more information.

|

| Dinner at Haddo House, 1884 by Edward Emslie |

It’s officially autumn (even though the temperatures do not reflect it where I live), and my menu planning is making a seasonal shift. As temperatures cool and winter approaches, a richer and more sustaining menu appeals. Soup is a favourite of mine for this time of year. An ancient dish, I suspect it evolved as soon as man figured out how to put edible things in a pot of water over heat. Soup is featured in virtually all culinary traditions and, of course, is a significant part of food history in Great Britain. As a history enthusiast, I enjoy reading details of normal life, including food, whether I’m reading fiction or non-fiction, as it gives an immediacy and life to the material.

|

| The Forme of Cury |

Peasant fare, elegant fare, or invalid fare, soup was a staple of the British diet. Early cookery books don’t show as many recipes for soup as for other dishes. I suspect this is because it was assumed that individuals already knew how to make the standard daily dish for the household, made from local ingredients to personal taste. The Forme of Cury, a cookbook from c. 1390 (originally a scroll showing authorship by “the Chief Master Cooks of King Richard II”), contained some soup recipes designed to be served to the nobility. The names frequently included “soppes” or sowp” as the dish was served over bread. One was “Fenkel in Soppes” which was shredded fennel, cooked in water and oil with onions, seasoned with saffron, salt and a spice mixture (“powder douce” which was a sweet spice mixture, left to the cook’s taste, that would contain some combination of cinnamon, galangal (related to ginger), nutmeg, sugar, etc.). It was served over toasted bread. Another similar recipe was “Slete Soppes”, which called for sliced leeks (white part only) to be cooked in wine, oil and salt, also served over toasted bread. A rather different matter is a “Cold Brewet”, which combines ground almonds cooked in wine and vinegar, seasoned with aniseed, sugar, green fennel shoots with ginger and cloves and mace. Cooked chopped kid and chicken meat is transferred to a clean dish, seasoned with salt and pepper, and boiled with the almond mixture. This soup was served cold.

During the Georgian era, turtle soup was considered the ultimate in elegant fare. Live sea turtles were captured and kept for fresh meat by sailors. Any left were brought in by sailors returning to port in the 1740’s-1750’s and sold for very high prices to the nobility. The popularity of the turtle was assured. At one point, as many as 15,000 live turtles were brought into England in a year. Different cuts of turtle meat had flavours reminiscent of fish, veal, beef or pork. The Compleat Housewife by Eliza Smith contains instructions for cleaning and preparing turtle soup. Once the meat from the body and fins are cleaned, cut them in pieces and stew together until tender, then strain off the liquid. Thicken the liquid and put the meat back in with kyon butter (possibly a compound butter of some kind), spices, pepper, salt, shallots, sweet herbs and Madeira wine to taste. The dish is put into the deep shell of the turtle, and baked in the oven. The extreme cost of a live turtle and the flavours of the meat resulted in recipes for Mock Turtle Soup, which used a variety of substitutions for the turtle, including beef, veal, oysters, tongue and calves’ heads. Hanna Glasse’s recipe includes a calf’s head (including the tongue and brains), veal broth, force-meat balls and eggs. The 67th edition of Mrs. Rundell’s A New System of Domestic Cookery published in 1844 contains 3 recipes for Mock Turtle Soup. Mock Turtle Soup maintained its popularity into the 20th century. (One could even find canned varieties.) Lewis Carroll based his character, the Mock Turtle, in Alice in Wonderland on this soup (a turtle with the head and back feet of a cow).

|

| The Mock Turtle from ALICE IN WONDERLAND by John Tenniel |

Soup recipes evolved over time as new ingredients became available and tastes changed. A classic example of this was Mulligatawny Soup. This soup was a chicken soup flavoured with curry. Rea Tannahill in Food in History indicated this soup appeared in England in the 18th century. British trade in India had been established since the 17th century and curry became a popular seasoning during the Georgian era. By the Victorian era, this soup was very popular. The edition of Mrs. Rundell’s A New System of Domestic Cookery mentioned previously has 4 recipes. The word “mulligatawny” (also spelled Multaanee and Malagatanee) was a corruption of the Tamil for pepper water. (The Tamil are an ethic group found in India and Sri Lanka.) The basic recipe called for onions and shallots, 2 chickens (or rabbits) pepper, butter, curry powder and turmeric, 2 quarts of strong broth, lemon juice and, if desired, a little curry powder to make it hotter. Keep in mind that curry powder was a spice mix made at home, to personal taste. (See English Historical Fiction Authors blog HERE.) One variation included cloves, and some garlic; another was made with veal, and the fourth included peas. This was a good way to use up leftover meat or vegetables. Subsequent versions included chopped apples. Cream could also be added; coconut milk may have been included. This soup is also still popular today.

Over the centuries, soup has been a common thread in culinary history. As we look back at some of the older recipes, the variety of seasonings and ingredients that are used today may seem surprising. We may not combine ingredients in exactly the same way, but it is easy to imagine how some of these soups may taste and the pleasure felt by the diners as they enjoyed them, whether elegantly spooning turtle soup at a formal dinner or enjoying the warmth of mulligatawny soup on a cold fall evening.

|

| "Fall In For Soup", engraving by Edwin Forbes 1876 |

Dickson Wright, Clarissa. A History of English Food. 2011: Random House Books, London.

Glasse, The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy. A new Edition, with modern Improvements. Introduction by Karen Hess. 1805: Cottom & Stewart, Alexandria, VA. (Facsimile by Applewood Books, Bedford, MA)

Rundell, Maria Eliza Kettelby. A New System of Domestic Cookery: Founded Upon Principles of Economy and Adapted to the Use of Private Families. From the Sixty-Seventh London Edition. 1844: Carey and Hart, Philadelphia, PA. (Nabu Public Domain Reprint)

Smith, Eliza. The Compleat Housewife. 16th edition, with Additions. 1858: London. (Reprint edition published 1944: Studio Editions Ltd., London)

Spurling, Hilary. Elinor Fettiplace's Receipt Book. 1986: Penguiin Books Ltd. Hammmondsworth, England.

Tannahill, Reay. Food in History. 1988: Three Rivers Press, New York, NY.

Websites:

THE FORME OF CURY. HERE

History.com. “A Spot of Curry: Anglo-Indian Cuisine” by Stephanie Butler, April 26, 2013. HERE

GoogleBooks.com. Rumble, Victoria R. SOUP THROUGH THE AGES: A Culinary History with Period Recipes. 2009: McFarland & Company, Ind. Jefferson, NC and London. HERE

All illustrations from Wikimedia Commons Images, except for the cover of Elinor Fettiplace's Receipt Book, which is a scan of my personal copy.

About the author:

Lauren Gilbert holds a BA in English and is a long-time member of JASNA. She lives in Florida with her husband, and is the author of Heyerwood; a Novel. Another book, A Rational Attachment, is in process and will be coming soon. Please visit her website HERE for more information.