by Elaine Moxon

In ancient times it wasn’t possible to keep whole herds through winter, so minimum livestock was retained and the rest were slaughtered and salted. The killing and preserving was done at ‘Samhain’ (summer’s end), which marked the start of the Celtic New Year. The last crops also had to be harvested by the last day of October (or its equivalent date of the era), Samhain-Eve. The festival of Samhain would last for three days from 31st October until 2nd November, thus crossing the border between the Old Year and into the New Year. Hence, Samhain is a time of change and transition.

To welcome friendly visiting ancestral ghosts, candles were lit on shrines in the west of the home to honour lost loved ones who had passed to the ‘Summerlands’. At the customary feast, a place setting would be set for those absent, and food and drink left for the ‘guest’ at the front door. The door would remain unlocked to allow the dead to enter. For spirits with no family to visit, additional offerings would be left on window sills and doorsteps. To keep away those with malevolent intentions, turnips or mangelwurzels were carved into ‘death’ heads with ghoulish expressions and left outside with a candle glowing inside. This has been replaced in many places with the pumpkin heads we see in abundance at Hallowe’en.

Samonios - October-November in the Celtic calendar, meaning ‘seed fall’

Samhuinn - beginning of winter: OBOD (pronounced ‘sow’ as in cow – ‘inn’)

Samhain - November, Irish Gaelic

Samhuin - All Hallows, Scottish Gaelic

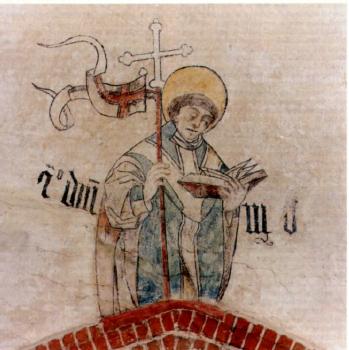

By the 7th Century the three days of the festival were Christianised as follows:

- All-Hallows Day, 31st October

- All-Saints Day, 1st November

- All-Souls Day, 2nd November

Nationwide [Britain]

The ‘Wild Hunt’ swept through the skies at Samhain, with one of several figures at its head depending on the belief system of those at ground level:

- In the north, Odin

- In Germania, Woden

- In Wales, Gwynn ap Nudd, King of the Fairies

- In England, Herne the Hunter or King Arthur

- In Scotland, ghostly hunters with hawks on their hands, followed by packs of hounds known as Gabriel’s Ratchets.

Scotland

Folk traditions attempted to obliterate this otherworldly connection through ritual and pranks (today’s trick-or-treat). Young men impersonated spirits with masks and veiled or blackened faces. The boundary between the sexes was blurred too with girls and boys wearing clothes of the opposite sex. Ploughs and carts were driven away and gates moved or tossed into ponds and ditches. Horses were led away and left in other people’s fields.

Ireland

The ‘Feast of Tara’ was a great assembly held at Samhain when renewal of kingships and kingdoms took place. Offerings were thrown to the gods into a sacred fire, in thanks for the year’s harvest and prayers were said for the forthcoming year. Ideally, four provincial kings and their kinfolk would sit in a square around the High King who sat at the centre; a symbolic assertion of the order and stability of the people. This was important to establish at such an unstable time of year, when the growing forces of darkness and chaos threatened with the long hours of darkness outside.

Fire kept away cold, discomfort and wild animals, as well as evil spirits. As recent as the 19th Century in Britain and Ireland, people would light brands from a large bonfire and run around fields and hedges of homes, surrounding parish boundaries with a magic circle of light. The ashes from the fire were later sprinkled over the fields to protect them from evil during the winter months (improving the soil at the same time!).

Here, too, young men would create hullabaloo throughout the countryside, marching in large groups blowing horns and wearing white sheets and horse’s heads. On hearing the horns, housewives would offer cakes to the approaching marauders as to deny them offerings would result in trickery. Once again we see here the underlying mischief, born of more serious ritual, that today is performed by countless children knocking doors for sweets.

Wales

At Samhain, a large fire would be lit in the hearth and families would gather to consume warm, sweetened ale from a ‘wassail’ bowl. Roasted apples and nuts were used in divination games to foretell the fortunes of the following year. Here we find a source for the apple bobbing and games of conkers that are so popular among children and adults alike! Apples have long been associated with immortality and can be found in numerous myths and legends from around the world. The Goddess Idun of Norse mythology was the keeper of the apples of immortality that were fed upon by the gods of Asgard to retain their immortality. Likewise, in Greek mythology the Goddess Hera owned a sacred apple tree, attended by three sisters known as the Hesperides. In Celtic myth the famous isle of apples, or ‘Avalon’ was an otherworldly paradise to which King Arthur was taken by three fairy queens (one of whom was Morgan Le Fay, fay meaning ‘fate’). Apples also link to the triple goddess that abounds in Celtic and Pagan religions and is where we find the symbol of the pentacle or five-pointed star/star of knowledge – when the fruit is cut horizontally.

A harvest supper known as the ‘Hag’s Feast’ would be shared at Samhain, in honour of the winter hag or crone, who rules between Samhain and Imbolc (1st February). This ‘dark goddess’ ruled the inner tides of human emotion, the ‘womb’ of the ocean and the realm of dreams. The darkness of the womb gives birth to human life, as the dark of night and winter gives birth to day and springtime. Thus this figure and her time of year were about restoring and regenerating spirit, inner strength and hope. She has now been transposed into solely her darkest aspect, as the witch riding through the land on a wolf (or broomstick!) striking down signs of life with her wand of winter. The sign of the dark goddess is the black feather and her birds are carrion and so here we find the crows and ravens of Hallowe’en. It is also worth noting the two ravens belonging to Odin from Norse mythology.

Modern Pagans use this time to also connect with loved ones who have departed and for introspection. Feasting and familial gathering form part of a remembrance service where worries can be released onto paper and burned in the ‘Samhuinn fire’, which can be as elaborate as a large communal bonfire or as intimate as a single candle flame in ones home.

As you choose your costume and prepare to embark on a night of chaos and ghoulish fun, consider the ancient rituals you will be sharing with our ancestors!

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

OBOD – Samhuinn & Alban Elued [Autumn Equinoxe]

Hamlyn History - ‘Myths Retold’ by Diana Ferguson

‘Visions of the Cailleach’ by Sonita d’Este & David Rankine

‘Pagan Feasts’ by Anna Franklin & Sue Phillips

ALL IMAGES: courtesy of Visualhunt.com

~~~~~~~~~~

Elaine writes historical fiction as ‘E S Moxon’. Her debut 'Wulfsuna' was published January 21st, 2015 and is the first in her Wolf Spear Saga series of Saxon adventures, where a Seer and one named ‘Wolf Spear’ are destined to meet. She is currently writing her second novel, set once again in the Dark Ages of 5th Century Britain. You can find out more about Book 2 from Elaine’s website where she has a video diary charting her writing progress. She also runs a blog. Elaine lives in the Midlands with her family and their chocolate Labrador.

Blood, betrayal and brotherhood.

An ancient saga is weaving their destiny.

A treacherous rival threatens their fate.

A Seer's magic may be all that can save them.

WULFSUNA

~