by Wanda Luce

According to Francis Bacon in 1605, “Cleanliness of body was ever deemed to proceed from a due reverence to God.” The religious reformer, John Wesley, furthered this belief by coining the phrase “Cleanliness is next to godliness.” Hmmm. Well, although I could not think it the first in a lineup of ways to show reverence to deity—for certainly the state of one’s heart and substance of one’s deeds merit the upper numbers in that distinct list—it does bear consideration as an essential component of man’s reverence for himself and others. After all, anyone who has been subjected to the dreaded stench of b.o. will quickly assert that cleanliness is at least a great service to mankind.

We are extremely fortunate to have running water, but a great many generations have had to maintain a semblance of good personal hygiene without such conveniences. But did they? Well, let’s take a quick look at what our ancestors did to get ready for that special someone.

I’ll wager you have all had those dreadful moments when your nose has been accosted by the smell of someone who has not thought a shower or bath worth his while. We are most of us too kind to make a stink about “the stink,” but it never escapes us, and most of us head in the other direction if at all possible. But what did they do a couple centuries ago before Mitchum or Degree arrived on the scene to spare us such unpleasantries? Well, hang with me for a few more paragraphs, and I’ll give you a few tidbits.

I’ll wager you have all had those dreadful moments when your nose has been accosted by the smell of someone who has not thought a shower or bath worth his while. We are most of us too kind to make a stink about “the stink,” but it never escapes us, and most of us head in the other direction if at all possible. But what did they do a couple centuries ago before Mitchum or Degree arrived on the scene to spare us such unpleasantries? Well, hang with me for a few more paragraphs, and I’ll give you a few tidbits.The Medieval set had some interesting notions. Some in that time thought bathing was a form of sexual debauchery. Others thought a person who bathed allowed the devil to come into him. Still others believed that allowing water to touch them when naked could make them very ill. In spite of those who held to such silly ideas, a great many did subscribe to the benefits of washing themselves, especially during outbreaks of the Black Plague. They found that frequently washing their hands and surroundings with warm water, wine, or vinegar helped reduce the Plague’s spread.

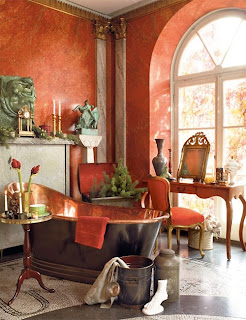

Medieval kings and lords and their ladies had special rooms set aside just for bathing or had large tubs brought into their rooms. Imagine the work it took to put together such a bath. First, servants had to draw the water, then heat it, and lastly cart it to the bather’s room. Perfumes, scented oils, and flower petals were often added. If peasants looked with envy on the lifestyles of the Medieval rich and famous like they do today (and I am sure they did), then they must have been jealous of their ability to regularly enjoy such luxury.

The less fortunate usually drew one bath for the whole family, and they all used the same water. The eldest bathed first then the next oldest and so on. From this came the saying “don’t throw the baby out with the water.”

Peasants rarely submerged themselves in water rather they cleaned themselves with water and a rag. Occasionally they savored the indulgence of some soap out of animal fat and wood ashes.

You might be surprised to know that it was standard practice to wash one’s hands before entering the great hall for a meal. Knights brought home soap from the east during the crusades. Before that, water and the oils of flowers were used.

And of course, rivers, lakes, and ponds were used for washing in the warmer months. If you are familiar with the expression “you will catch your death of cold,” then you understand why washing by the poor was often reserved only for warm weather.

I write Regency-era romances and have done some study on bathing practices during that time period. In the early 18th century it was customary to wash one’s hands and face daily, but full body bathing was only done once every few weeks or months! Egads that’s scary! By the end of the century, however, cleanliness had begun to come into vogue, especially as a result of Beau Brummel’s example and advocacy. Free-standing showers powered by a hand pump began to be used by those who could afford them

Well, if you want to have a little fun, follow the link below and make yourself a batch of homemade soap using lye. If you are really adventurous, make the lye yourself. Don’t forget to mix in some great scent then hop in the tub with it and get a taste of the bathing experience in past centuries.

http://www.cranberrylane.com/soapmaking.htm

Wanda Luce, Regency Romance Author

wandaluce.blogspot.com

Wanda Luce, Regency Romance Author

wandaluce.blogspot.com

.JPG)