|

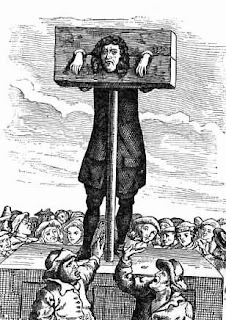

Back then, extortion and bribery were rife – you could be imprisoned on some trumped-up charge by a crooked sheriff or bailiff just so they could take money from you in return for your freedom, even if you hadn't actually broken any law! If you had committed some criminal act, even a minor one, you could expect a fine you'd struggle desperately to pay, or some other even more humiliating punishment like the pillory. This was a wooden board that held the criminal's head and hands while the crowd threw things at them. A butcher selling bad meat would be dragged through the streets on a hurdle before being locked in the pillory where he'd have the offending offal burnt under him.1

And if you were a woman caught stealing? You'd be taken to the nearest river and drowned!2

No wonder some people chose to go into hiding and become outlaws rather than face medieval justice...

|

| The pillory (burning offal not shown) |

With so many being forced into a life outside the law it wasn't unusual for well-organized criminal gangs to spring up and cause trouble for the unlucky people living in the villages and towns of England. John Fitzwalter, for example, who led a gang that besieged Colchester not once, but twice, holding the whole town to ransom. 3 Or the notorious Folvilles, a group of brothers who murdered a man and fled the country but were able to return – with pardons – in 1326, thanks to the help of Roger Mortimer. They robbed, raped and murdered their way around the country for the next couple of years before being captured. They simply joined Mortimer's army and were pardoned again whereupon they resumed their reign of terror. They continued in this way for many years before, finally, their luck ran out, the law caught up with them and this time they were beheaded.4

One of the bounty hunters employed to catch both the Folvilles and another murderous gang, the Coterel's, was Roger de Wensley. He managed to find the Coterels but rather than dispensing justice he joined them!5 The Coterels were, like the Folville's, 'gentlemen' who, as well as being vicious criminals, served in King Edward III's army, were bailiffs and even Members of Parliament.

The funny thing is, like Robin Hood, the Folville's eventually came to be celebrated rather than vilified by the common man. They kidnapped an apparently corrupt justice of the peace, killed a widely-hated judge and were, in the years after their death, generally seen as men who had righted wrongs. 6

Fulk Fitzwarine is another outlaw cum-folk-hero, this time from the thirteenth century and, although he was a recorded historical figure, he may have been the source of some aspects of the Robin Hood legend. Outlawed for treason, he rebelled against King John twice. Despite this the people of the time celebrated him in poetry and song, drawing in elements from Arthurian mythology - Merlin himself was supposed to have prophesied Fulk's exploits!7

Medieval England was a dangerous place, even if you were a law-abiding citizen. You might be accused of a crime you hadn't committed so some corrupt lawman could extort money for your release from jail, and, if you were a notorious, violent criminal you could be pardoned from the most heinous transgressions by making yourself useful to those in power. The sheriff in my novels, Henry de Faucumberg, was a real historical figure who had a criminal record for assault and, on more than one occasion, stealing wood before he found himself serving the crown as Sheriff of Nottingham and Yorkshire. 8 Justice? “...it is estimated that there were more outlaws at this time than at any other period in England's history.” 9 No wonder – it seems like you could get away with anything back then as long as you had money or well-connected friends to help you out.

What interests me the most about all these accounts is how the outlaw – a criminal after all – usually becomes a romantic hero to the common people. The Folvilles raped and murdered for years yet a generation after their death they were celebrated as heroes poking a finger in the eye of the ruling classes. The original ballads of Robin Hood portrayed an incredibly violent man whose followers murdered an innocent child (in Robin Hood and the Monk) while he himself beheads the honourable Sir Guy of Gisbourne, sticks the head on the end of his longbow and mutilates the face with his knife!10

What is it about these dangerous men that makes them so compelling, so heroic, to the common people, even when they're clearly operating outside the laws that supposedly hold our society together? I believe it's mostly down to the old idea of “sticking it to the man.” Everyone likes to get one over on those in charge, especially when the rulers are rich and you're barely able to afford a crust of bread to feed your starving children. The medieval ballads sprung up around the Folvilles, Clim of the Clough (who appeared in a story alongside Adam Bell 11) and Robin Hood because they prospered in the face of adversity and gave hope to the common people that they too might, one day, break out of their life of thankless servitude to their betters.

|

| Adam Bell, Clim of the Clough and William Cloudesley |

700 years later audiences still enjoy tales of anti-heroes within literature and film: Batman and Judge Dredd, for example, represent the ultra-violent face of modern fictional 'justice', yet both are miles away from our Western judicial systems in the way they deal with criminals.

It seems our fascination for justice outwith the judicial system continues to this day. Maybe, eventually, the lawmakers will get things right – crimes will be detected, the perpetrators will be dealt with fairly and proportionately, the little man will enjoy justice as much as the wealthy, and the likes of Eustace Folville, Robin Hood and Batman will no longer seem so romantic...

Aye, right!

|

| Judge Dredd and Judge Anderson bringing justice to the lawless in Dredd 3D |

Steven A. McKay is the best-selling author of the Amazon "War" chart number 1's Wolf's Head and The Wolf and the Raven. The third in the series, Rise of the Wolf, is nearing completion, while a spin-off novella, Knight of the Cross, has just been released. All his books are also available from Audible as audiobooks.

To find out more go to StevenAMcKay, Amazon UK, or Amazon US

1 Mortimer, Ian The Time Traveller's Guide to Medieval England, p95

2 Ibid, p219

3 Ibid, p240

4 Ibid, p240-242

5 Ibid, p241

6 Jones, Terry Medieval Lives, p63

7 Phillips, Graham and Keatman, Martin, Robin Hood – the man behind the myth, p115

8 http://midgleywebpages.com/shirereeve.html

9 John Paul Davis, Robin Hood – the Unknown Templar, p89

10 http://www.boldoutlaw.com/rhbal/bal118-gisborne.html

11 http://www.robinhoodlegend.com/adam-bell-clim-clough-william-cloudesly/

Interesting article and important questions, but I feel compelled to point out that the average peasant in the 12th century was enduring unprecedented prosperity. Due to radical improvements in agricultural technique, yields had increased dramatically in Western Europe and the European peasant (including serfs) was, according to Professfor Rodney Stark, for the first time in human history growing to their full genetic capability -- taller and stronger than people anywhere else on the planet at this time. Peasants were not struggling for a crust of bread while the lords lived well. On the contrary, for the first time they were strong -- and wealthy enough -- to 1) fight back and 2) start developing their own legends. When looking for an understanding of the popularity of anti-heroes, I think you are on the right track comparing today rather than imputing a desperate poverty that did not exist! Income inequality was probably FAR LESS in the 12th and 13th Century than it is today. Noblemen's income did not exceed the income of peasants to the same orders of magnitude by which the top 1% of Americans today exceed the incomes of our lowest quartile.

ReplyDeleteYou may well be right Helena but the medieval period covers rather more than just the 12th century. My own books are set in 14th century England where there was famine in the early years and the peasants WERE struggling for a crust of bread

ReplyDeleteSteven, I've tried to leave a comment 3 times but Google is making it difficult for me today, so I'm reduced to saying great post. The romanticizing of outlaws continued even into the 17th and 18th centuries with highwayman, pirates and smugglers. It's interesting how these stories have sparked the imagination then and now.

ReplyDeleteThank you! Yeah, I had problems posting earlier today too but I'm glad you persisted. :-)

DeleteCasting people out, without the protection of the law to support them, has always seemed a short sighted thing to do, to me. Guess what happens! But the public conversion to a legend is a curious thing. I am proud to be, very distantly, related to Dick Turpin and my namesake (Hobby Noble) was probably the worst of the lot. (His ballad is in the Oxford Collections) The development of the Robin Hood Ballads is interesting. Some were performed in the noble households while others were street songs; remembering that these were ideal ways of saying up-yours, it seems quite possible that they were rather brave protest songs

ReplyDeleteYep, Malcolm, it's interesting how the original Robin Hood was a man of the people but he was hijacked (!) by the upper classes and became a wronged noble.

DeleteCasting people out, without the protection of the law to support them, has always seemed a short sighted thing to do, to me. Guess what happens! But the public conversion to a legend is a curious thing. I am proud to be, very distantly, related to Dick Turpin and my namesake (Hobby Noble) was probably the worst of the lot. (His ballad is in the Oxford Collections) The development of the Robin Hood Ballads is interesting. Some were performed in the noble households while others were street songs; remembering that these were ideal ways of saying up-yours, it seems quite possible that they were rather brave protest songs

ReplyDelete