A quick guide to ‘information technology’ during the Peninsular War

by Jonathan Hopkins

Military intelligence is a contradiction in terms or so the old joke runs. Of course that was based on generals’ continued fallback option in later wars: throwing masses of lightly armed and unprotected men against emplaced infantry, machine guns and artillery in the forlorn hope they commanded higher numbers than the opposition and the basic tactic of 18th century warfare still worked..

It’s far different nowadays, in an age of satellite imaging and unmanned drones. But even though the Duke of Marlborough had famously written that ‘no war can be conducted successfully without early and good intelligence’ it wasn’t until 1803 that a Department of Military Intelligence was proposed in Britain, by Robert Brownrigg who had accompanied Frederick, Duke of York, as his military secretary, on the abortive expedition to Holland in 1799 and who realised the system of using local knowledge, in widespread operation at that time, was rubbish, basically.

But Brownrigg found recruiting operatives to the DMI was a major headache. Though governments employed spies, the army was above such ungentlemanly shenanigans. Intelligent young officers, attracted originally by a home posting, soon found sifting through mounds of often conflicting information far less attractive than they had first imagined, apart from the fact that many were ostracised by friends once their occupation became known.

A spy? Hrrrmph! Not the done thing, old boy.

Most transferred out of the fledgling department pretty sharpish once they realised this, so by the time Wellington landed on the Portuguese coast in August 1808 he was no better off than Marlborough had been on his march across Europe to the Danube a hundred years earlier.

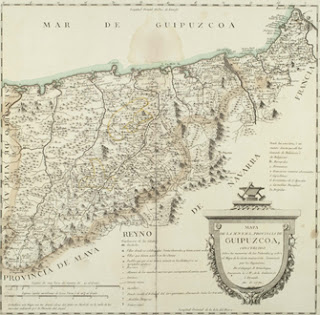

The first problem the British had was a dearth of maps. Wellington originally relied on those of cartographer Tomas Lopez (‘tolerably accurate’ according to the University of Southampton). Their main failing was they showed few contour details, critical information when it came to moving large numbers of troops and quantities of equipment by road. Or dirt track, which is what Iberian thoroughfares usually were.

It was exactly this which prompted Sir John Moore, in the autumn of 1808, to gamble on splitting his force in three when he crossed Portugal into Spain. Locals convinced him that because of the state of the roads, the only way he could get his horse drawn artillery safely to Salamanca was on a circuitous journey through Estremadura, to the south of his preferred line of march

As it turned out, the guns could have managed Moore’s central route without too many problems, so since he did not know exactly where the French were he had risked any one of his under-strength divisions meeting the enemy unexpectedly through a lack of good intelligence.

Once Wellington returned to Iberia the following year he set about solving these problems. He saw immediately how useful intimate local knowledge was when Colonel John Waters, who had remained in Portugal after the British left, found boats which enabled Wellington’s troops to cross the Douro at Oporto un-noticed by Marshal Soult’s army and create a strongpoint from which they were able to run the French out of the city and thence from Portugal, at least for a time.

The Duke had no specialist cartographers, but he did have a few engineers who possessed similar skills. When not required on other projects these men were sent out, often with a cavalry escort, initially to map areas ahead of the British line of advance, but later to survey vast tracts of Portugal and Spain. As they moved about the country and became familiar to the local populace they would often receive information from the natives about French positions which they passed on to headquarters, and thus the more generally known role of ‘Exploring Officer’ (they were called ‘Observing Officers’ in many period despatches) was born.

Edward Charles Cocks was one such officer, though he was a captain in the 16th Light Dragoons rather than an engineer. As well as mapping the countryside Cocks watched for troop and supply movements which might indicate where the enemy were likely to strike next. His cavalry escort meant he was usually able to pass messages back quickly, without needing to either return to headquarters personally or risk Portuguese or Spanish couriers of unknown reliability.

As the war progressed, however, the network of known partisans grew. Messages could travel shorter distances between couriers so went faster. In addition, Wellington had made it known he paid cash for captured French dispatches, and it seems he did not much care how they were obtained. There are anecdotal tales of them being received still smeared with their original carrier’s blood. For their part the French pursued a policy of extermination against any individual or group they believed had helped the British, fueling the growth of Iberian guerrilla movements and ensuring even more information reached Wellington’s ears.

Exploring Officers wore full uniform for the simple reason that if they were captured they could claim they were combatants (which, technically, they were) and should be afforded all privileges their rank demanded. Spies caught in civilian clothes would likely be shot, though that did not stop many Exploring Officers going about in disguise. Captain Dashwood, an officer on Moore’s staff, dressed himself in a Spanish shepherd’s cloak and hat before walking brazenly into the occupied village of Rueda to check on the numbers of French troops in residence, before strolling casually back out again.

The most important piece of Exploring Officer’s equipment was usually a good horse. John Waters was captured at one point but bided his time until his escort was distracted. Then he galloped off, outrunning pursuers thanks to his mount’s superior fitness and stamina.

Being able to live by your wits helped, too. When Colquhoun Grant was captured in 1812 he somehow got sight of a letter from Marshal Marmont accusing him of spying and suggesting he be refused exchange for a captured French officer, normal practice at the time. Grant considered this allowed his to break his parole - his promise not to try to escape. Passing himself of as American, he made his way to Paris and mailed a number of intelligence reports to Wellington from the capital before escaping back to Britain by boat.

Eventually, semaphore stations were constructed in Portugal, helping messages travel even faster, though these were restricted to coastal areas. They never made it into the Spanish interior and it seems likely that was due to the terrain. But given the number of times the British advanced into and retreated from Spain between 1809 and 1813 it’s unclear how much use they would actually have been.

And I suppose the final piece of our IT jigsaw was George Scovell’s success in finally cracking the Grand Chiffre, France’s method of coding messages.

So there you have it. The Peninsular War was really won using wits, pen and ink, fast horses and friendly Spaniards. They would’ve loved Google Earth and SatNav.

Well, maybe not SatNav ;)

~~~~~~~~~~

Jonathan Hopkins is a Napoleonic Cavalry enthusiast.

His second novel Leopardkill - A Cavalry Tale is now available on Kindle with the paperback to follow on 1st October 2013.

by Jonathan Hopkins

Military intelligence is a contradiction in terms or so the old joke runs. Of course that was based on generals’ continued fallback option in later wars: throwing masses of lightly armed and unprotected men against emplaced infantry, machine guns and artillery in the forlorn hope they commanded higher numbers than the opposition and the basic tactic of 18th century warfare still worked..

It’s far different nowadays, in an age of satellite imaging and unmanned drones. But even though the Duke of Marlborough had famously written that ‘no war can be conducted successfully without early and good intelligence’ it wasn’t until 1803 that a Department of Military Intelligence was proposed in Britain, by Robert Brownrigg who had accompanied Frederick, Duke of York, as his military secretary, on the abortive expedition to Holland in 1799 and who realised the system of using local knowledge, in widespread operation at that time, was rubbish, basically.

But Brownrigg found recruiting operatives to the DMI was a major headache. Though governments employed spies, the army was above such ungentlemanly shenanigans. Intelligent young officers, attracted originally by a home posting, soon found sifting through mounds of often conflicting information far less attractive than they had first imagined, apart from the fact that many were ostracised by friends once their occupation became known.

A spy? Hrrrmph! Not the done thing, old boy.

Most transferred out of the fledgling department pretty sharpish once they realised this, so by the time Wellington landed on the Portuguese coast in August 1808 he was no better off than Marlborough had been on his march across Europe to the Danube a hundred years earlier.

The first problem the British had was a dearth of maps. Wellington originally relied on those of cartographer Tomas Lopez (‘tolerably accurate’ according to the University of Southampton). Their main failing was they showed few contour details, critical information when it came to moving large numbers of troops and quantities of equipment by road. Or dirt track, which is what Iberian thoroughfares usually were.

It was exactly this which prompted Sir John Moore, in the autumn of 1808, to gamble on splitting his force in three when he crossed Portugal into Spain. Locals convinced him that because of the state of the roads, the only way he could get his horse drawn artillery safely to Salamanca was on a circuitous journey through Estremadura, to the south of his preferred line of march

As it turned out, the guns could have managed Moore’s central route without too many problems, so since he did not know exactly where the French were he had risked any one of his under-strength divisions meeting the enemy unexpectedly through a lack of good intelligence.

Once Wellington returned to Iberia the following year he set about solving these problems. He saw immediately how useful intimate local knowledge was when Colonel John Waters, who had remained in Portugal after the British left, found boats which enabled Wellington’s troops to cross the Douro at Oporto un-noticed by Marshal Soult’s army and create a strongpoint from which they were able to run the French out of the city and thence from Portugal, at least for a time.

The Duke had no specialist cartographers, but he did have a few engineers who possessed similar skills. When not required on other projects these men were sent out, often with a cavalry escort, initially to map areas ahead of the British line of advance, but later to survey vast tracts of Portugal and Spain. As they moved about the country and became familiar to the local populace they would often receive information from the natives about French positions which they passed on to headquarters, and thus the more generally known role of ‘Exploring Officer’ (they were called ‘Observing Officers’ in many period despatches) was born.

Edward Charles Cocks was one such officer, though he was a captain in the 16th Light Dragoons rather than an engineer. As well as mapping the countryside Cocks watched for troop and supply movements which might indicate where the enemy were likely to strike next. His cavalry escort meant he was usually able to pass messages back quickly, without needing to either return to headquarters personally or risk Portuguese or Spanish couriers of unknown reliability.

As the war progressed, however, the network of known partisans grew. Messages could travel shorter distances between couriers so went faster. In addition, Wellington had made it known he paid cash for captured French dispatches, and it seems he did not much care how they were obtained. There are anecdotal tales of them being received still smeared with their original carrier’s blood. For their part the French pursued a policy of extermination against any individual or group they believed had helped the British, fueling the growth of Iberian guerrilla movements and ensuring even more information reached Wellington’s ears.

Exploring Officers wore full uniform for the simple reason that if they were captured they could claim they were combatants (which, technically, they were) and should be afforded all privileges their rank demanded. Spies caught in civilian clothes would likely be shot, though that did not stop many Exploring Officers going about in disguise. Captain Dashwood, an officer on Moore’s staff, dressed himself in a Spanish shepherd’s cloak and hat before walking brazenly into the occupied village of Rueda to check on the numbers of French troops in residence, before strolling casually back out again.

The most important piece of Exploring Officer’s equipment was usually a good horse. John Waters was captured at one point but bided his time until his escort was distracted. Then he galloped off, outrunning pursuers thanks to his mount’s superior fitness and stamina.

Being able to live by your wits helped, too. When Colquhoun Grant was captured in 1812 he somehow got sight of a letter from Marshal Marmont accusing him of spying and suggesting he be refused exchange for a captured French officer, normal practice at the time. Grant considered this allowed his to break his parole - his promise not to try to escape. Passing himself of as American, he made his way to Paris and mailed a number of intelligence reports to Wellington from the capital before escaping back to Britain by boat.

Eventually, semaphore stations were constructed in Portugal, helping messages travel even faster, though these were restricted to coastal areas. They never made it into the Spanish interior and it seems likely that was due to the terrain. But given the number of times the British advanced into and retreated from Spain between 1809 and 1813 it’s unclear how much use they would actually have been.

And I suppose the final piece of our IT jigsaw was George Scovell’s success in finally cracking the Grand Chiffre, France’s method of coding messages.

So there you have it. The Peninsular War was really won using wits, pen and ink, fast horses and friendly Spaniards. They would’ve loved Google Earth and SatNav.

Well, maybe not SatNav ;)

~~~~~~~~~~

Jonathan Hopkins is a Napoleonic Cavalry enthusiast.

His second novel Leopardkill - A Cavalry Tale is now available on Kindle with the paperback to follow on 1st October 2013.

I'm currently drafting a spy thriller set in 1796 using a recurring character so this was particularly interesting, thank you!

ReplyDeleteMerci, madame :)

Delete